7,000-year-old milk fat sheds light on Neolithic farming – and it doesn't even smell

Fatty molecules found in old Mediterranean milk pots show diary farming as widespread – with Greece as the exception.

Greasy molecules found in 7,000-year-old used milk pots have shown that dairy farming was widespread in the Mediterranean in Neolithic times.

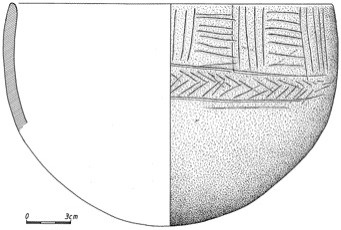

The fatty molecules have been tucked away in pores in the glazed pottery for thousands of years, and chemical analysis shows that they are from the milk of cows, sheep and goats. These greasy stains, combined with information on Neolithic herd management, have shed light on how and when dairy farming caught on in the Mediterranean. The study is published in the journal PNAS.

7,000-year-old milk

"When you've got glazed pottery the fats penetrate into it and remain here quite secluded for a long time, until we extract them," study co-author Mélanie Roffet-Salque of the University of Bristol told IBTimes UK. "When you think that a bottle of milk will last a few days, and yet we're able to detect [milk residue] in pots that are that old – it's incredible."

"We've been developing this radioanalysis method for more than 20 years and testing whether the lipids are archaeological," Roffet-Salque says. The lipids are very degraded, she says, and they are not likely to be modern contaminants. Her team have been able to use radiocarbon dating on the tiny amounts of lipid found in the pots to confirm that they are indeed millennia old.

Herding practices written in bone record

Roffet-Salque and her colleagues compared this data with analysis of bones found around the sites where the pottery was dug up. The bones held information on the ways in which the animals were used – for meat, or for dairy. The age at which the animals died is a clue as to what they were used for, says study co-author Roz Gillis of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, France.

"The age-of -death for cattle, sheep and goat provide an insight into slaughter management practices," she says. "Herds for dairy are slaughtered at different ages in comparison with those slaughtered primary for meat."

For example, when cows are used for dairy, there is a spike in the number of calves being killed just after weaning, the authors say. Calves were needed to release the milk of these Neolithic cattle varieties, unlike modern dairy cows, which can release milk merely at the sound of the dairy machine. When animals are used primarily for meat, they were mostly killed once they had reached their full size, as there was little point in keeping them for longer.

Ancient Greeks preferred pigs

The study found that across the Mediterranean, cows, sheep and goats were being used for milk soon after the domesticated animals were introduced in the area. The ways in which the animals were used differed across the Mediterranean: mainland Greece was a notable exception, the authors say.

"It's shown by the milk pots," says Roffet-Salque. "In Greece there's no milk in pots and no sign of herding strategies oriented to milk production. It might be cultural, it might be environmental. We're not completely sure about what's happening there."

Pigs may have played a bigger role in the diet than cows, sheep and goats on mainland Greece, says Gillis. "Processing pigs within the same ceramics as milk [was also common], which can cause a mixture of signals," she says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.