Antibiotic-loving bacteria don't just resist drugs, they get a kick out of them

Strains of E. Coli exposed to the antibiotic doxycycline grew colonies three times larger than normal.

Developing antibiotic resistance has been found to give the disease-causing bacterium E. coli an additional boost, making it grow faster and become fitter after repeated exposure the antibiotic doxycycline.

The mutations that give E. Coli resistance to doxycycline also made them reproduce faster and grow colonies three times larger than ordinary, non-resistant E. Coli. The research is published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The researchers exposed E. Coli to eight rounds of antibiotics over four days. In that period, the bacteria gained a number of mutations. One of the mutations was linked to antibiotic resistance, giving the bacteria more pumps to remove the drug from the cell.

The second mutation was to delete a large section of its genome that is normally involved in helping the bacteria coat a surface by forming a 'biofilm'. This section of DNA is actually the remnants of a virus, which causes the cell to split and spill its contents, helping other cells to grow nearby to form a film.

The E. Coli in the study were grown in a liquid culture, in a similar environment to the human bloodstream. Here, without the need to form a biofilm, the E. Coli cut out this section of DNA – which makes up 4% of its genome – when exposed to doxycycline, allowing it to devote its energy to growing faster and forming larger colonies instead. Even when the exposure to doxycycline was stopped, the bacteria did not lose this newly-gained trait.

"We didn't anticipate the viral change at all," study author Robert Beardmore of the University of Exeter told IBTimes UK. "That was much stronger than the pump mutation in evolutionary terms. We saw more strength with selection and a faster change on quite a large chunk of the genome."

This property was not unique to doxycycline, and similar features were found in two different classes of antibiotics, Beardmore said. However, only certain strains of E. Coli gained these mutations when exposed to the antibiotic.

"It's not every antibiotic and it's not every E. Coli, and certainly not every bacterium. But it is pretty strange that that feature is there," Beardmore said. "There's something special about the way doxycycline is inhibiting the cell that causes these features."

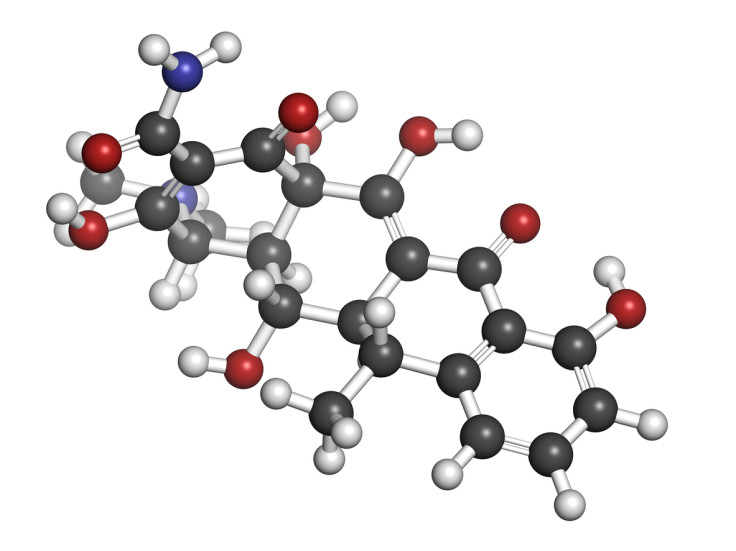

Doxycycline is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used for a number of infections, such as chlamydia, Lyme disease, pneumonia and acne. It's also used as a preventative treatment for malaria, and can be taken for months for a trip to a country where the disease is prevalent. This widespread use means the antibiotic can be found in the environment, such as in rivers and soil.

If E. Coli is exposed to doxycycline in the environment, it could quickly develop the mutations to grow larger colonies as well as becoming resistant to the antibiotic, Beardmore said. However, he said that doxycycline should not be dropped as a treatment for various kinds of infection.

"Doxycycline may be a perfectly good drug to treat a range of bacteria with. But when E. Coli comes into contact with it in a river or field, if it's got the right kind of genome then you'll see these effects and doxycycline will boost the growth."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.