Director Ken Levine Tackles the Beast of America

BioShock Infinite developer talks US Election and the future of video games

Computer games have reached a pivotal moment. With the tug of war between art and industry finally evening out, and a new generation of home consoles expected in the very near future, videogames are about to become smarter, more popular and more sophisticated than ever.

America, too, has reached a tipping point. Its once impervious economy is still reeling from the worst double dip since the thirties, pushing employment, poverty and social dissonance to new heights. The political debate rages everywhere, from Capitol Hill, to the streets of New York and the blogosphere. Occupy versus Tea Party, left versus right; Democrat versus Republican.

For Ken Levine, creative director at Irrational Games in Boston, and self-proclaimed "political junkie" it's business as usual. Ever the visionary, his work bridges creativity and commercialism, regularly topping sales charts whilst probing what computer games can be. His current project, BioShock Infinite, is set to analyse America's role as a global and historical power, drawing parallels between the US politics of today and the Exceptionalist ideals as laid out by the Chicago World's Fair.

Columbia

Set in 1912, aboard a floating city called Columbia, the game puts players in control of Booker DeWitt, a former Pinkerton agent on one last job. Ostensibly sent to Columbia to rescue a woman named Elizabeth, DeWitt finds himself caught in a civil war between the ultra-left Vox Populi and the staunchly conservative Founders party.

Guns are available to everyone. Built on absolute American ideals, Columbia's government takes the Constitution literally, distributing free rifles as part of the right to bear arms. It's what Levine calls his "Skinner box", an experimental space used to study psychological behaviour:

"We don't try to go into these things with a particular axe to grind", explains Levine. "We try to set up little social labs. You can't really do that in the real world; you can't really set up these little Skinner boxes...It's hard in the real world to take a piece of ideology and let it play itself out.

"So, we ask ourselves what would happen if these places existed, be it an Objectivist utopia or a quasi-religious slash American Exceptionalist utopia."

Levine's previous game, the original BioShock, dismantled the Objectivistic philosophies outlined by Ayn Rand, imagining a world where man's idealistic determination to fulfil himself leads to his downfall.

Masterpiece

It was a masterpiece of game design, replacing cutscenes with a lustrous environment in which players could find their own morality. BioShock Infinite is primed to ask similarly searching questions, throwing religion, American history and contemporary bipartisanism under the spotlight:

"Although Infinite is set in 1912 it still reflects the politics of today," continues Levine. "If you look at which states vote for which party, originally they were the states that fought each other in the Civil War; they haven't really changed.

"The current political conversation in America is exhaustingly the same conversation that's been going on for hundreds of years. We are very much like two countries. America has been this bifurcated thing for a long time.

"The American Exceptionalism, theocracy-based power structure has been around the edges of American culture for a long time. BioShock Infinite gives it its full day in court.

"It's very much reflective of the current scene and the historical scene, and I think that's demonstrated by things like the Occupy Movement and the Tea Party coming around during the course of the development of the game. When we started the game, there was no Tea Party and there was no Occupy Movement - during the development of Infinite those movements came around and really changed the nature of Infinite's conversation."

Voice of the People

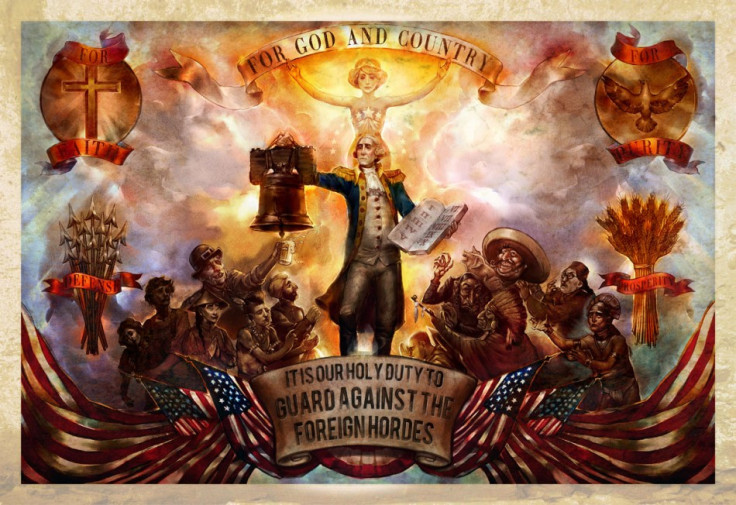

Columbia is a city of two halves. On one side is the Founders, wealthy, conservative and predominantly white. On the other is the Vox Populi, Columbia's multi-cultural, disaffected masses. They're routinely trodden on by grotesque Founder propaganda, which warns Columbians to "Guard Against the Foreign Hordes."

It would be easy to dress up the Vox as Infinite's good guys, stringing them out as plucky, worthy underdogs. But Levine isn't interested in taking sides. He wants to give his characters, and the philosophies he picks on a more thorough interrogation:

"Part of the challenge in Infinite has been finding the value in a lot of broad ranging belief systems, because if I'm just critical of them and I don't connect with them, how can I write about them?

"The racial issues in the game are a huge challenge, because how do you relate to this guy [Comstock, the leader of the Founders] who is racially biased? You really can't, so the question is why; why is the society this way? And that leads to some very interesting conversation.

"You have a mix of racial and class biases coming together in Columbia; the leader of the Vox Populi is very different from the leader of the Founders, in that she's African-American and poor. Comstock is white, Protestant and wealthy. And that was interesting as a starting point but not enough, because obviously there are a lot of white, Protestant wealthy people who don't have racial bias. So we wanted to look at what made him that guy.

"If you go and look at Atlas Shrugged or The Fountainhead, Rand can populate her books with these kinds of superheroes of her ideals, who can carry out her ideals to their extremes and never stumble.

"They're very convenient for her but they're not human beings. I try to make these games a more honest look at utopian ideals, but also, they have some commentary on the weakness of games themselves, particularly the illusion of free will in games. So I try to light my house on fire a bit, too."

Research

Ayn Rand aside, Levine's research into BioShock Infinite has taken him as far back as the Declaration of Independence, right up to the Civil Rights movement and Occupy Boston:

"My job as a writer is not to try and express my opinion - it's to reveal motivations to people. I know people in the Occupy Movement and I know people in the Tea Party, so I spent time talking to those people and understanding their view of the world... we went down to see Occupy Boston last year.

"History is much more important toInfinite than the first game. It's tied to events like the Battle of Wounded Knee, certainly one of the darker chapters of the extended warfare between Native American tribes and the US government. The Boxer Rebellion also comes into it, in some ways.

"There are stronger religious themes in this game, too, themes that are present in several religions."

Columbia resonates a believable roundness; likeBioShock's Rapture, it's a kind of beautiful mess, bright, colourful and picturesque, but fatally flawed by its ideology. It's a mechanical place, kept afloat by steam-punky air balloons, and patrolled by robotic security guards:

"My research was mostly historical and somewhat theological," says Levine. "But there was also a lot of scientific research. I hadn't picked up a science book since high-school chemistry, so we brought in some consultants from MIT.

"There are some very particular books, philosophically challenging books that I don't want to give away yet...a lot of people look for a syllabus around BioShock, which I think will come after the game's released."

Opaque

It's not just Columbia, or the philosophies that surround it that Levine aims to muddy. His characters, too, come under intense scrutiny, their backgrounds and motivations intently developed by the Irrational writing team.

Where the central figures in a lot of first-person shooters come off as one-dimensional, Levine's cast is refreshingly opaque:

"Booker's motivation is very simple. He has this gambling debt, and rescuing Elizabeth is his last chance at writing that off. He's not had a good run of it, his life is a mess. Even when he pays off his debt it's not like he's going to become President or something - his goal is just to survive.

"Meeting Elizabeth changes him. They're central to each other's lives and they transform each other...their relationship is revelatory about each other."

Elizabeth is at the centre of BioShock Infinite. Imprisoned in Columbia since she was a little girl, she possesses an unstable ability that lets her interact with other time periods.

In combat, it allows her to conjure weapons and defilade that have otherwise been destroyed; when trying to revive a dead horse, she accidentally transports herself and Booker to 1983:

"The most interesting thing about Elizabeth," explains Levine "is that she doesn't really understand why she's special. She has all these amazing abilities, but she's also a babe in the woods type figure. She's never been out of this tower since she was a young girl. Her and Booker are about as opposite as you can get - he's seen everything and she's seen nothing. Somehow they merge into this team."

Comstock, the idealistic leader of the Founders is another of BioShock Infinite's main players - according to the trailers, he holds some key to getting Elizabeth out of Columbia.

A narrow faced, pale conservative, Levine was eager to paint him as more than an archetype, throwing the conflict between the Founders and the Populi into question:

"Writing Comstock was very difficult. It took a long time to come to grips with his motivations...he's alien to me. I had to figure out how he came to be that guy.

Roosevelt

"I spent a lot of time reading about Teddy Roosevelt, who's such a fascinating figure because he doesn't really fit into any political mould that you would see today. He was extremely progressive, in regards to the environment and anti-trust issues, and, when it came to global politics, almost neo-conservative.

"He was very engaged in projecting America's power throughout the world. He didn't have a cynical bone in his body, but he had views that would probably be abhorrent to people on both the left and the right...You don't really see people like that anymore.

"He was a progressive on issues of race and class, but he would speak in the most crass - what we would call racist - way about Jewish and black people. If you look at the politicians of that time, they'd use these awful racist slurs in their letters and conversations because that was just the accepted view at the time.

"Even the Civil War Abolitionists - even Lincoln himself - viewed African-Americans, not as slaves, but not really as people either; they would assume some role, some lessened role in society. Because these men were products of their time. Great men like Jefferson and Washington were slave holders, even though they were opposed to slavery in a lot of ways.

"They were fascinating men because of their contradictions, not because of their idealised versions... It was interesting to try and create a world where it wasn't an extreme position to have these viewpoints; that it was part of that culture, part of that society."

Social conscience

It's too early to tell how successful Infinite will be in its satire; even Levine admits that "the proof will be in the pudding." But with the rise of the Tea Party and the Occupiers, Columbia's war between the Vox and the Founders couldn't have been better timed.

A happy accident some might say, but for the Wall Street protests to break out after Infinite began development it shows just how firmly Levine and Irrational have their ears to the ground.

Computer games are rapidly approaching mainstream acceptance; the next step is cultural relevancy. Shooting people, hopping on mushrooms and throwing birds around is all well and fun, but for games to truly evolve into the next console generation, they need to start paying attention to what grown-ups talk about - money, sex or in BioShock Infinite's case, politics.

Ken Levine is a rarity in mainstream gaming, a consummate entertainer with a mile-wide artistic streak. More than that, he has a social conscience:

"If you don't sense these tensions at the roots of society you're not really paying attention," he says. "I don't see why games, as a medium shouldn't be able to respond to real life. There's an odd tension where you're controlling a character but also telling a story about the character, but there's no reason we should back away from that tension.

"People ask me all the time if games should be able to talk about these issues, and I think "why the hell not?" Give me a reason why games should be kept out of any conversation. We're just another medium, and the conversation about games happens around any new medium - that it's somehow lesser and dangerous to children. That's just the way it is. That will pass in time."

As censorship debates grow ever more silent, BioShock Infinite represents a new kind of dangerous game. Its fascination with ideologies, institutions and the effects of subscribing to either is more likely to mess with the brains of adults than turn The Children violent. Already, responses have been mixed:

"Infinite continues the BioShock thematic of exploring the nature of extreme political movements and their effect on people, but that's really the starting point of this game...I think it's going to be a point of entry for a deeper discussion.

"When I first showedInfinite to my parents, they read it as an attack on the principles of the Tea Party. Then when we showed the demo at E3, which had a lot of stuff with the Vox Populi, I remember reading on some Occupy websites that it was an undermining of the labour movements and the Occupy movements...unfortunately I ended up on a white supremacist website where the game was - I quote them - 'designed by the Jew Ken Levine as a manual to demonstrate how to kill white people.'

"As much as I find some of that uncomfortable, if everybody reads the game the same way we're missing an opportunity. It's about looking at what games can and can't talk about. I like the idea that it's a Rorschach."

Cynicism

BioShock Infinite's most biting satire comes from its refusal to pick sides. In a climate of partisan politics, gay marriage debates, #TeamRomney and #TeamObama, Levine's commitment to finding his character's motivation, to disassembling clear cut political ideologies like Objectivism and Exceptionalism, represents a depth of understanding rarely found in mainstream media, let alone computer games.

Troubled by historical conflicts like the North/South voting divide, Levine's work explores the cynical middle ground:

"I think to take sides you have to be more idealistic than I am. The conflict between the Vox Populi and the Founders doesn't really get resolved. I think to have it all get wrapped up would not be reflective of the existing left/right conflict.

"Political positions are often secondary to our nature; the idealistic natures of political movements are sullied by our weakness as human beings. We're not as strong as our ideals...I think the American Utopian ideals that Jefferson and Franklin and Adams set out to make were designed specifically with a kind of cynical viewpoint. You can't just make a set of ideals and expect those to change people."

"It's easy to get trapped in an idealistic cycle," concludes Levine. "Thomas Jefferson said that the tree of Liberty must be watered with the blood of tyrants. - I think that reflects a certain degree of cynicism about society."

Computer games are at a pivotal moment. Until now, they've been guilty of forming ideologies, their narratives relying too heavily on good versus evil, absolute victory and absolute defeat. It's a behaviour reflected in television smear campaigns, presidential debate rhetoric and far-wing extremeists.

With Ken Levine and BioShock Infinite taking games into the political arena, both of those problems are finally open to debate.

BioShock Infinite is due for release in February 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.