Nazi Victims' Plight for Art Recovery: Lessons from the Gurlitt Affair

When local tax authorities executed a search warrant in the bohemian part of Munich, Schwabing, they probably had very little inkling that they would stumble upon one of the most unique finds in postwar Germany; the undeclared inheritance of 1406 artworks stemming from the Nazi-era.

They were also probably not aware that they would open a Pandora's Box of thorny legal and political problems.

As news reports first began to circulate about the Cornelius Gurlitt art stash, the first questions on the minds of Nazi victims and their heirs were: Are our paintings among the stash? How can we find out about it if they do not disclose what artworks were found in the Gurlitt apartment?

The first press conference from the Augsburg prosecutors was not very promising. Everyone who suspected that their artworks were among the Gurlitt stash expected that the letters that they wrote to authorities would lead to a response.

This meant that Jewish families who lost their heirlooms to the Nazis would all be kept in the dark without the possibility to check for themselves as to whether their art was amongst the Gurlitt stash. They would have to rely on others.

The response was, thus, completely unacceptable.

Finally now, in response to the outcry, the Gurlitt artworks are now being posted on the internet and can be researched directly by the families who lost these works and by their representatives (see www.lostart.de and www.lootedart.com).

But what about the bigger picture? If a family finds an artwork, which was lost in the Nazi-era amongst the Gurlitt stash, can they legally get it back?

Unfortunately, like most things in life, the answer to that question is complicated.

Legal Issues

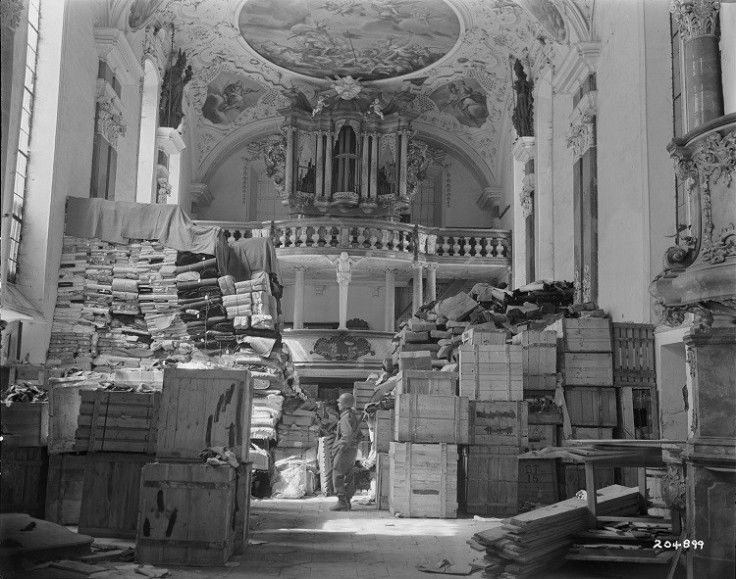

The Gurlitt artworks are on German soil, in the Schwabing district of Munich, not far from the infamous Brown House where the National Socialists had their headquarters. It was later used by the Allies after WWII as the collecting point for Nazi looted art.

From a legal point of view, German civil law recognizes claims for stolen property, even going back to WWII.

This was confirmed only recently by Germany's highest court in a case called Sachs, where the heir of a Nazi victim reclaimed his father's poster collection from a German museum, after it was looted by the Nazis.

However, in the Sachs case, the German museum did not assert Germany's 30 year statute of limitations. If it had, the return of the Sachs poster collection may have been time barred.

Applying the Sachs case to the Gurlitt case, Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of Hildebrand Gurlitt who was appointed by the Nazis to deal in what the Nazis termed "degenerate art", is a private individual who says he wants his father's art back, no matter how it was obtained.

It is very likely then, that not being a public museum, he would assert Germany's 30 year statute of limitations.

However, in the Gurlitt case, the 30 year statute of limitations rule may be set aside because his mother claimed that all of his father's paintings had been destroyed in the Dresden fires during WWII.

Thus, potential claimants would not have known that these artworks existed due to her deceit, which might also be attributable to her son, Cornelius Gurlitt.

In addition, as a result of the "l'affaire Gurlitt" the German legislature is looking into the possibility of the elimination of the statute of limitations defense with respect to Nazi-era art claims.

This would certainly be a welcome development, which would greatly assist Nazi victims and their heirs, to claim back their lost family art.

With respect to Nazi looted art in public museums, the principles of the 1998 Washington Conference apply to the 46 countries which have accepted which includes Germany.

Had the Gurlitt stash been found in the basement of a German museum (or for that matter any public museum within a country which is a signatory of the 1998 Washington Conference) it would be obligated to research the provenance of each individual artwork. It would also be under obligation to, where possible, locate the heirs and then reach a "fair and just solution."

That is the way it works on paper at least.

In reality, museums too often do not follow the Washington Conference principles. They hide Nazi era artworks with confusing and misleading provenances, and when confronted with the facts they delay decisions, and seek ways to keep artworks 'lost' due to Nazi persecution in their collections.

In such cases in many countries, claimants have the possibility to bring their claims to a national art commission to obtain either a binding or non-binding recommendation regarding their claims.

Where the Gurlitt case will lead is still an open question, but one thing is for sure, a spotlight has been put on this issue and the world has changed since Mr. Gurlitt was found in his Schwabing apartment with his Nazi era art.

David J. Rowland is an attorney in New York City with the firm of Rowland & Petroff. He represents many families who lost art in the Nazi era. He writes and speaks regularly regarding Nazi era art issues.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.