WWI 100th Anniversary: How Britain's 'Devil Dwarfs' Helped Allies Win World War One

"Your country needs you," bellowed Lord Kitchener from the infamous sign-up poster, his pointing finger emerging from a resplendent moustache. Except one group of men, who Kitchener thought he didn't need.

They weren't the archetypal Tommy Atkins: the sort of strapping, strong-jawed British soldier who stood six feet tall and adorned the government's army recruitment propaganda during the First World War.

Neither were they asked, as most other British men of fighting age were, to fight for king and country on the frontlines, from the Somme to Gallipoli.

Instead these men had to fight first on the home front, before being sent with the rest of their peers into the flesh-shredding carnage and trench misery of World War I. All because they were short.

Yet by the end of the war, they had established themselves as some of the most fierce, reliable and loyal soldiers in the conflict, fighting alongside each other in what became known as Bantam Battalions.

As one poem by an unknown author put it:

Each one a pocket Hercules

five feet and a bit,

a kind of Bovril essence

of six feet British grit.

5ft 3in or taller

By 1915, the generals of the British Army had realised that what would later be called the Great War for its scale, length and intensity would not end anywhere near as quickly as they had first thought.

To keep fighting and match the German war machine, hordes of the Empire's young men would have to be called up. Millions were asked to volunteer, before in 1916 the army became so desperate for numbers that it resorted to coercion through conscription.

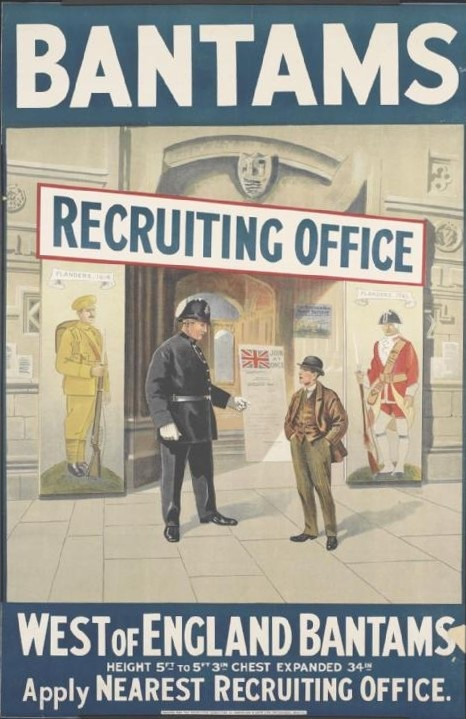

Criteria were set for the volunteers. Men would have to be aged between 19 and 30; they must have a minimum chest size of 34in; and they must be 5ft 3in or taller. Automatically, tens of thousands of fit, healthy men were written off because they were too short.

Some had it in their genes. Some had been malnourished as children raised in harsh Victorian poverty. Others were the sons of generations of miners, whose growth had been stunted down the years by the grim, gruff work they did in claustrophobic underground tunnels.

Most were ready and willing to fight, they just weren't allowed. There were even reports of these brave men being mocked at Army recruitment stations, despite being among the first to hold up their hands to be sent into battle. One, a coal-heaver called James Robertson, wasn't allowed inside the London Scottish Regiment headquarters to put his name down.

"They said: 'Get away home, Titch,'" Robertson, who was just one inch below the regulation height, later recalled. "I told them 'I'm all Scottish', but they just laughed and said 'To get in, there'd have to be two of you!'".

The patronising attitude shown towards short soldiers sits awkwardly with the fact that some of history's fiercest fighters have been small. In 1914, the average height of the Japanese adult male was 5'3. Yet the Imperial Japanese Army had built up a serious reputation as a powerful force because of its brutality, having left a horrifying trail of massacre in its small footprints.

15th Battalion, 1st Birkenhead

For one anonymous Durham miner, the rejection became too much. He had marched 150 miles from street to street, starting in Durham and ending in Birkenhead, repeatedly getting knocked back. At 5ft 2in, not one recruiter would sign him up.

By the time he had arrived in Birkenhead, the miner was furious. It was at the city's recruitment centre that he cracked. Having been told once again he was too short, he threw his coat to the floor and offered to fight any man in the room to prove that the missing inch mattered not.

According to the Birkenhead MP at the time, a 6ft 6in demi-giant called Alfred Bigland, the miner "raged and swore" until the recruiting sergeant "with great difficulty got him out of the office".

This inspired Bigland to write to the British Secretary of State for War Kitchener. The policy must change, urged Bigland, and groups of "bantam" fighters – healthy men between 5ft and 5ft 3in with a minimum chest size of 34in – could be formed. They would be named bantams after the pugnacious fowl, a creature that would be their motif.

Kitchener didn't reply. But his underlings did. They liked the idea, but said the War Office couldn't afford the time and resources to form such outfits. As a compromise, they said they would provide the equipment and some financial support. But the responsibility of raising a Bantam Battalion would fall to the town of Birkenhead alone. So Bigland did.

Thus the 15th Battalion, 1st Birkenhead, The Cheshire Regiment was formed. It was the founding Bantam Battalion, but the idea soon spread. By the end of the war in 1918, such was their success and reputation, there would be 29 of these Bantam Battalions across Britain and Canada, formed in three divisions - the 35th, the 40th and the Canadian Expeditionary Force - with 50,000 having served in them.

Devil Dwarfs

Perhaps because many felt they had a point to prove, Bantams became known for their ferocity as combatants. The 18th Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry (HLI) was based in Glasgow, a tough Scottish city known for its brawlers and brutes, where locals had nicknamed them "The Devil Dwarfs".

"Zestfully as ready to a punch-up with a pubful of English soldiers as to storm a German trench, their quarrelsome reputation was legendary," wrote Sidney Allinson in his authoritative 1981 book The Bantams, a rare and comprehensive history of this largely overlooked story in WWI, which includes interviews with hundreds of Bantam Battalion veterans.

"Long before they reached France, the cantankerous 18th Battalion had earned their nickname, 'The Devil Dwarfs'. It was soon awarded for their record for brawling and general mischief which almost eclipsed even the awesome reputation of their sister battalions in the HLI [Highland Light Infantry].

"For all their recalcitrance, they had proved to be readily trained into smart soldiers on the barrack square and the assault course."

It wasn't just at home that they earned their status as big-hitting small men. It was in the horrific reality of frontline conflict that they became known, too.

In one daring raid on 8 June, 1916, 60 bantams from the 14th Gloucester set out for enemy trenches in France. After running ahead of German artillery fire, the shells exploding in their moments-old footprints, the Bantams reached the trench.

"The fight became a hand-to-hand brawl with every man for himself – confusion of bursting grenades, shooting, stabbing, and clubbing, while men screamed with the murderous voices of close combat," wrote Allinson in The Bantams.

"At the end of it, 30 Germans and eight British lay dead, and the enemy fled into the box-barrage where many more were killed. The bantam raiders scampered back to their own side, dragging a heavy Maxim machine-gun with them."

Duck's Disease

There were upsides and downsides to being short in WWI. In some ways, they were better adapted to life in the trenches. It was easier to scurry around in the narrow corridors and to live in the cramped chambers. And they could fit better in one of the war's deadliest and lasting creations, the tank, which was invented by Lincoln-based engineering firm William Foster & Co.

They were also less likely than taller fighters to unwittingly find their heads above the trench just enough to catch the eye of a German sniper.

"Some of the taller fellows in charge were inclined to say us small chaps suffered from 'duck's disease' - our backsides too close to the ground," said George Palmer, a Bantam with the 14th Gloucesters, in an interview with Allinson.

"Be that as it may, I never regretted my lack of height since the time a sniper's bullet hit the tree just above my head while I was making water. Any taller and I'd have been dead. I was soon down in the latrine pit, clean boots and all."

But when the trenches bogged as they did as heavy winter rains fell, Bantams struggled most of all to trudge their way through the muddy mire, their short legs often submerged to the thighs in stinking, glutinous brown goo. To be wounded was to drown in the mire if you were a Bantam.

Frighteningly Fewer Bantams

Like all others fighting on the WWI fronts, the Bantams suffered heavy losses. As men fell they were replaced, but not with the plucky, healthy men such as the first wave of miners and the like.

Instead, their muddied, bloodied boots were half-filled by underdeveloped men, recruited out of desperation to bolster numbers in a murderous slog that was trudging on for longer than all had expected. Shelled, machine-gunned, gassed. Battle by battle - and there were many - Bantams were knocked down like skittles.

"There were frighteningly fewer Bantams every hour and their reservoir of fit reserves was drying up fast," wrote Allinson.

"Divisional medical officers were so concerned at the low quality of replacements that they recommended the divisions should return back to the depots every man of poor physique who had arrived in recent drafts."

By Spring 1917, faith in the Bantams divisions was faltering amid sub-standard replacements and the scars of war. There weren't enough suitable small men left in Britain who could be called up to justify entire divisions. A message from the War Office dictated that "the Bantam standard must be disregarded for good and all". It was the end of the 35th (Bantam) Division, which contained the original Birkenhead Battalion, and the beginning of the end of the 40th (Bantam) Division.

The 40th Division lasted another few months. Its Bantams saw grizzly action at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, almost a year to the day before the bells of Armistice would knell for the war's death and its dead millions.

Cambrai was brutal to the 40th. Veterans of the battle recalled shrapnel "rattling like rain" and bullets that buzzed past their heads "like a swarm of bees". Others remembered "clumps of small bodies in khaki" and the choking acidic sting of gas attacks. The division's casualties were huge - over 4,000 men dead in just two days' fighting.

They had captured the German position at Bourlon Ridge, the prize Field Marshall Hague had longed for. A worthless consolation, in the end. It was lost again just one week later.

Grossly Unfair

In the years immediately after the end of WWI in 1918, the story of the Bantams had come full circle. Despite their contribution and losses, the Bantams faced the same struggle as in 1914. For many jobs, they were deemed too small. It was an echo from the army recruitment halls.

The matter was discussed in parliament when Captain George Garro-Jones, MP for Hackney South, raised the concerns of a constituent. Garro-Jones had been approached by a former Bantam soldier in the war who had been turned down for a job sorting mail at the Post Office because he was too short.

The Liberal MP was outraged and said he found the situation "grossly unfair". He had served alongside Bantams in France and remembered them fondly. He recalled one scene when the small soldiers hauled sand bags down and stood on them to see over the trench walls and fire at the enemy.

"Three days later that battalion took over the lines, and I found that along the whole line that particular difficulty had been overcome by every one of them," said Garro-Jones in the House of Commons on 20 July, 1925.

"I say without laying myself open to any charge of sentimentalising or anything of that kind that for a man of this kind to be rejected by the Post Office because he might require a small piece of board to stand on is a gross offence.

"No man who served his country, and who was strong enough and tall enough to carry a pack and to fire over the top of the trench, should be told that he is not strong enough to carry a bag of letters or not tall enough to reach the top pigeonhole in a sorting office."

Many others faced the same problem with the Post Office and it was raised again in parliament. But the cabinet minister in charge - Postmaster General Sir William Mitchell Thompson - refused to back down on the regulation height for mail sorters.

"There are a considerable number of applicants, but we have a very large number of applicants who are of suitable height, and it would be an injustice to them, and I am not prepared to abandon the Regulation," Thompson said in the Commons on 28 June, 1927.

Sir James Macpherson, a Liberal MP for Ross and Cromarty, was indignant in response to Thompson's flat rejection of his and others' pleas for a relaxation of the stiff rules.

"Is the right hon. gentleman not aware that the same objections which he is advancing now against the employment of men of that height were advanced by the War Office at the beginning of the War and is he further aware that no battalion covered itself with greater distinction than the Bantams Battalion?"

Duff Cooper, the Conservative MP for Oldham, pointed out that under the regulation, the diminutive French imperial hero Napoleon Bonaparte "would have been ineligible to be a postman".

Some Bantams did find fame and fortune, though not for their time in the war. Two of the best known names are Arthur Askey, the popular bespectacled entertainer, and Billy Butlin, who founded an empire of eponymous holiday camps.

Today, the Bantam Battalions struggle to be seen over the many towering tales of WWI. Their collective story is little known and much of what is can be put down to the efforts of Sidney Allinson's digging in the mud and blood of trench memories for his book.

Bantams didn't fit into the popular narrative about the hero Tommy then and they don't now. But, on the stories of their service and struggles, they stand just as tall as any man who fought in that gruelling war.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.