Battle of Passchendaele: The horror of World War One in the soldiers' own words and photographs

A new book tells the story of Passchendaele through the words and photographs of soldiers in the trenches.

On 31 July 2017, the world marks the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Passchendaele – one of the longest, bloodiest and most controversial battles of World War One. Appalling weather conditions had turned the Flanders lowlands into a mud-churned swamp rendering tanks immobile and virtually paralysing the infantry. Any gains either side made were almost invariably soon lost, and the battle became a war of attrition.

The battle was finally halted in in November 1917. Casualty figures are disputed, but it is thought around 310,000 Allied soldiers and 260,000 German soldiers lost their lives at Passchendaele.

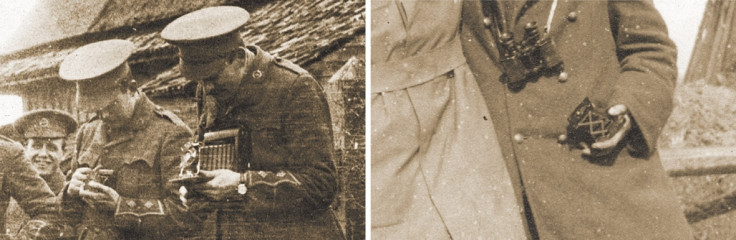

A new book tells the story of Passchendaele through the words and photographs of soldiers in the trenches. Historian and First World War expert Richard van Emden has compiled extracts from soldiers' letters, diaries and memoirs and photographs taken by the men with their own illicit cameras. The army had banned cameras just before Christmas 1914 when it was discovered that soldiers – mainly officers – were selling war photographs to the press.

Some of the most remarkable photos in the book were taken by Captain George Birnie, an Australian medical officer and keen photographer who was attached to the 8th East Surreys (18th Division) at Passchendaele. He was wounded in the shoulder by a piece of an exploding shell, but he carried on treating the wounded until he was relieved some eight hours later. He was later awarded the Military Cross for gallantry during active operations against the enemy. His images capture the desolate conditions of the battlefield and the camaraderie of the men in the trenches.

The book covers the four distinct battles on the Western Front in 1917: Arras (early April to mid-May), Passchendaele (July through to November) Messines (June) and Cambrai (late November to early December).

Van Emden writes: "1917 [was] a year of unparalleled misery on both sides of the line: an end to the war was nowhere near in sight, and popular enthusiasm for the struggle had long since eroded. The struggles ... were characterised by a grim resignation to the necessity of attrition and gradual battlefield predominance in men and arms. All in all, 1917 completed the transition to the 'wearing out' war. And, perhaps for the first time, the soldiers began to question the competence of their most senior commanding officers."

31 July 1917, the first day of the Passchendaele offensive, started well for the Aliied troops, but by the afternoon, casualties increased as they met with stiffer resistance, and then the drizzle turned into pouring rain. In his account published in 1920, Major William Watson, D Battalion, Tank Corps, wrote: "It began to rain, and it rained until 6 August, and then it rained again."

The tanks had mixed success: some did sterling work, but many became hopelessly stuck in the thick mud. Two-thirds of those deployed were eventually bogged down and many were gradually destroyed as they floundered.

Lieutenant Edward Allfree, Royal Garrison Artillery, wrote: "To give some idea of the mud, I need only mention that I saw a horse, harnessed to a French wagon, with its hind legs so deeply sunk in the mud that it could not move. Its hind legs were buried right up to its haunches, so that its stomach was level with, and lying on the ground, with its front legs stretched straight out in front of it along the ground." Allfree also described how the shell-churned mud was so bad that it took a stretcher party of six, four hours to bring in one wounded man.

On 10 August, the weather relented, permitting an attack close to the Menin Road. The attack was a disappointment and over 2,000 casualties were sustained for a maximum gain of 400 metres.

A few days later, as the troops were preparing to launch an assault on the German village of Langemarck, a shell screamed over the head of Second Lieutenant Henry Foley, Somerset Light Infantry, and burst with a deafening crash behind him. "I swung round," he wrote, "and saw that where but a second before had stood some thirty men, chatting and joking as they slipped on their equipment, there was now nothing but an appalling shambles. The shell had landed right in among them. Many men were simply blown to pieces. All told, this one shell cost us twenty-six casualties – practically a whole platoon gone."

The battle was disintegrating into a grinding, attritional struggle, with limited gains. There was no prospect of a breakthrough, just the slow wearing down of an enemy who could least afford the losses. Private Thomas Hope, Liverpool Regiment, wrote: "We flounder in and out water-logged shell holes, stumble over foul-smelling heaps of putrefying flesh, or, as machine guns sweep the ground, crawl over the more recent dead of the morning's advance, which emit strange noises – half groan, half sigh – as the weight of our bodies presses the air from their lungs."

August 1917 was not a success for the British troops, but their fortunes seemed to improve – along with the weather – as September arrived. They were pushing the German troops back in a methodical series of assaults.

On 17 September, Private Hugh Quigley, Lothian Regiment, wrote: "The country resembles a sewage heap more than anything else, pitted with shell holes of every conceivable size, and filled to the brim with green, slimy water, above which a blackened arm or leg might project. It becomes a matter of great skill picking a way across such a network of death traps, for drowning is almost certain in one of them."

Private Hope wrote this vivid account of a nighttime push across the German line: "A machine gun suddenly spurts out right in front of us, and automatically we drop flat. Some I notice drop clumsily and lie still; others clutch frantically at limbs. The gun rattles again and is easily located in the semi-darkness by its flashes streaming from a concrete pillbox. We crawl on our stomachs from shell hole to shell hole. At last we have wormed our way round, and are now to the rear of the emplacement where we form in a semi-circle with bombers a few yards in front. There is a sudden rush, and it is all over. Regardless of uplifted hands three of the occupants are bayoneted as they emerge from the narrow entrance, before we realise what we are doing. It is not that we are brutalised, but we are so keyed up to killing, that our minds can't relax quickly enough.

"Prisoners emerge from dugouts, their hands in the air, fear and bewilderment expressed on their faces. Still dazed from the terrific bombardment, which has passed over them like a scourge, they are almost childish in their desire to show friendliness, dreading the unknown future, yet eager to leave behind the hell from which they are escaping."

The offensive was driven on throughout October, regardless of the worsening weather. It did not rain on 1 October but it did for twenty-four of the thirty-one days that month. Conditions that had bedevilled the start of the campaign, returned with a vengeance.

There were further advances on 4 October and again on 9 October, with further bites out of the German line. Battlefield conditions now precluded any further use of tanks, The next step would be taken on 12 October. Private Hugh Quigley of the 12th Royal Scots would be going over the top for the first time. He wrote: "With rifles slung, and great trepidation in our hearts, we scrambled up and went forward into the heat of the flame. One sight almost sickened me before I went on: thinking the position of a helmet on a dead officer's face rather curious, sunken down rather far on the nose, my platoon sergeant lifted it off, only to discover no upper half to the head. All above the nose had been blown to atoms.

"Apart from that, the whole affair appeared rather good fun. You know how excited one becomes in the midst of great danger. I forgot absolutely that shells were meant to kill and not to provide elaborate lighting effects, looked at the barrage, ours and the Germans' as something provided for our entertainment. We got the first objective easily, and I was leaning against the side of a shell hole, resting along with others, when an aeroplane swooped down and treated us to a shower of bullets. None of them hit. I never enjoyed anything so much in my life – flames, smoke, lights, SOS's, drumming of guns, and swishing of bullets, appeared stage properties to set off a great scene. Then going across a machine-gun barrage, I got wounded. At first I did not know where, the pain was all over, and then the gushing blood told me."

The Allied troops failed to make any useful impression on the enemy positions, barely reaching the first objective and in many cases ending up back where they had started. Artillery guns were sinking axle deep into the mud, some deeper. The action was called off. The battle dragged on into November. What the Germans required most was persistent bad weather and it was granted in bucketsful. The fighting continued, advance up the line onto the Passchendaele Ridge, as much to get the troops onto dryer ground as to finally take this long-term objective. The offensive was finally halted on 10 November.

Major George Wade, an officer serving in the 20th Light Division, captured that sacrifice and undoubted heroism of the men on both sides of the war when he wrote about conditions near Langemarck. "There were a number of wounded men lying about on the knee-deep muddy battlefield and conditions were so impossible that no stretcher-bearers or carrying party of any kind could rescue them. They lay dying in icy shell holes or in the open. It was so bitterly cold that they did not mercifully bleed to death but just lay there in hopeless misery. For six days one of our men, shot through both legs, lay out in no-man's-land, which was periodically swept by rain, hail, snow, machine-gun fire, and shrapnel from both sides. Each night Germans from a nearby shell hole crept out to give him a warm drink, every drop of which they must have longed for themselves as their plight was as bad as that of the British."

In contrast to the long, muddy months of stalemate at Passchendaele, the Battle of Cambrai which followed it was decisive and unexpectedly swift. At 6.20am on 20 November, a 1,000 gun bombardment smashed enemy batteries and defences before the tanks rolled over the enemy's barbed wire, while the infantry followed, using the tanks as cover. The Hindenburg Line was breached with comparative ease, allowing the cavalry to exploit the breakthrough.

As the troops moved forward, one village after another fell. But then the momentum slowed and the Germans regrouped and counter-attacked, recapturing most of the ground lost on 30 November. British troops fell back in confusion; it seemed likely that large numbers of men would be cut off and surrounded. The fighting subsided and then officially ended on 4 December. The year's four offensives had cost Britain and her Empire around 450,000 casualties, or an average of around 2,700 casualties each fighting day, and that figure excludes the attritional losses in merely holding the line.

Young Private Hope was wounded in early December while carrying an urgent message across the open. His time at the front had lasted less than five months. On 8 December, he wrote of his mixed feelings as an ambulance carried him away from the front. "The day for which I have longed and prayed has arrived. I am going down the line, away from it all, and yet a strange feeling mars my happiness. It is something almost beyond my ability to explain. I am leaving this manmade hell. That occasions my joy and also my sorrow, my joy at escaping from the shadow of death so lightly, my sorrow at losing all the things that shadow gave me.

"And those staunch comrades I'll never see again on this earth. Mac, who rests peacefully in a little cemetery on a gentle Picardy slope. Webby, who has no known grave, whose restless spirit must ever haunt the waterlogged flats of Flanders, prowling unseen over rain-soaked ridges and hovering in the valleys at dawn with the morning mist as its shroud, seeking, always seeking, the resting place that was denied its earthly form. Streaky, Naylor, Taffy, old Bellchamber, and all those others I knew.

"Whatever is before me and whatever life brings, I must always be a better man for having known these things and lived with such men."

For more of the soldiers' accounts and photos, many of them previously unseen, get The Road to Passchendaele by Richard van Emden, published by Pen & Sword Books, at £20.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.