Blockchain experts discuss fake news and reputation

Cornell's Emin Gün Sirer, Mihai Alisie of the AKASHA project and Steemit's Dan Larimer weigh up the options.

The question of how a reputation-based peer-to-peer system could combat the growing problem of fake news is under debate. Some people working with technologies like blockchain are concerned about social media corporations employing censorship – prompting a need, they say, for decentralisation; others pointed to the challenge of designing effective reputation systems within such contexts.

Decentralisation delivers many good properties but it makes certain things, which are easily done in a centralised architecture, very difficult. The evolution of the web from its early days is in the direction of decentralisation, but people may underestimate the value of middlemen and brokers, whose job is mediating reputation.

In the context of decentralised news, it's difficult to decide what constitutes a reputable source. The traditional approach is something like Google's PageRank algorithm, which computes a single global metric of "goodness". How high up the rankings a news source appears may be very important to that news provider, but what do we actually mean by an objectively good source of information?

A team from Cornell University, which created Credence – a decentralised way of using reputation in a peer-to-peer filesharing context – decided utility would be a better way to grade reputation. Rather than basing it on principles, reputation in the Credence ecosystem is grounded in historical evidence that a peer contributed useful resources to the system – it's this that is voted on.

Emin Gün Sirer, a professor at Cornell's Computer Science Department, said the notion of a universally good source is odd; it's really about what the user wants. "We stayed away from the Google approach," he said, "from trying to compute an objective metric because there is no such thing as objectivity whether it's news or any other source. Instead of a single global metric, we wanted to compute a user-specific metric."

A common pitfall with reputation systems is the naïve and rather dumb way they are done. A typical example is the eBay model of rating people you had a good experience with and would business with again etc.

"That's an okay thing to do but it's very gameable," said Gün Sirer. "It's very easy for the bad guys to just love each other's stuff and they create these tightly connected networks where they vote each other up. There is no cost to that. They can just do this all day long and look highly reputable to honest users of the system."

Gün Sirer said blockchains provide an excellent infrastructure for building new things like reputation systems on top of, and that's what we are starting to see in 2017.

"Now we are beginning to see the identity layer start to emerge and once you have identities then you can have reputation systems. There will be many contenders that provide many different notions of identity; there won't be one. And there will be many different reputations, just like we have many different reputations on the internet.

"That's a good thing and I hope the people who are trying to build these systems actually look back on work that was done earlier and take some lessons from it," he said.

Allowing identity and reputation to become interoperable will require open and transparent standards, which will remove the fragmentation that exists today giving users full control over their digital self.

Putting "reality filters" back in the hands of users (along with their data) is a good way to tackle fake news and the attendant problem of internet corporations thinking about applying censorship, according to AKASHA Project, a censorship-resistant social network fused out of Ethereum and IPFS.

The project's leader Mihai Alisie, who was also a co-founder of Ethereum, said that unlike other social networks, AKASHA does not rely on servers and users communicate directly with each other.

He takes a fresh view of the fake news issue. For example, when a journalist publishes a story about someone, he/she could tag (or mention) the person in the story similarly to how you tag people in photos. Untagged articles will be less reputable and you could even set your filter to display only verified and tagged articles.

"The identities tagged in the article could review and markup the articles with corrections, scores and reactions. Readers could give extra weight to those values and contribute thoughts, scores and reactions," said Alisie.

"Soft publishing to tagged identities for review can allow for innocent mistakes to be caught early with no damage to identities. Individual identities operating under group identities such as authors under a publisher can feel residual effect through greater social awareness.

"Identities will most likely have multi-dimensional reputation attached so being reputable in one context can impact reputation in another context or group. For example, issuing corrections and apologies are taken as recovery modes to signal good faith reputation while accuracy reputation remains.

"A new reader coming across an author who doesn't adhere to the community standards can still choose to follow but is now better informed of the reputation and credibility of the information source," he said, adding that this is just one of the many solutions that can be explored to solve the problem of fake news with these new technologies.

Steemit is a popular blockchain-based social news service which debuted last year. Text is stored in a blockchain and authors who get upvoted can receive a monetary reward in a cryptocurrency called STEEM.

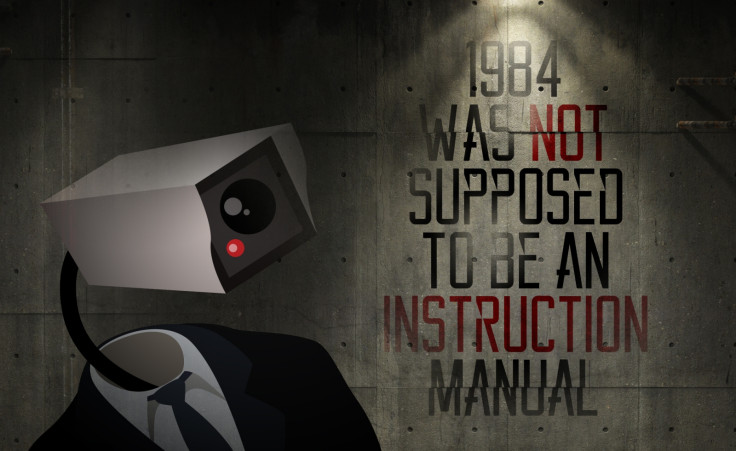

Dan Larimer, co-founder of Steemit, said there is no shortcut to eliminating propaganda and fake news but pointed out that censorship is much worse. "The power to censor is the power to manipulate reality as perceived by the masses. Propaganda (fake news) also has the power to manipulate the reality of anyone who fails to consider all opinions," he said.

"The difference is that propaganda only works on those who trust the source of propaganda. Once that trust is lost the propaganda loses all power. Censorship, on the other hand, denies people the opportunity to think for themselves.

"The mainstream media propagandists have been losing their power thanks to the free speech enabled by the internet. In response to their loss of power, they are proposing censorship as the solution. It should be clear to all thinking people that censorship is worse than any propaganda because it grants power over propaganda to a single group."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.