Chernobyl 30th anniversary: What does the future look like in the exclusion zone?

It has been 30 years since the worst nuclear disaster in history occurred. On 26 April 1986, reactor 4 exploded during a routine test at Chernobyl nuclear plant, situated on the Ukraine-Belarus border. The blast and the resulting fire released huge quantities of radioactive material into the atmosphere – about 300 times greater than that of the Hiroshima bomb in 1945.

The devastating consequences for the region, its environment and its inhabitants are still being felt today. This will probably not change in a near future. When we look back, in 30 years' time, at the impact of the Chernobyl nuclear explosion, many of today's questions will likely still remain.

Radiation levels within the exclusion zone

Soon after the disaster, the Soviet authorities established an exclusion zone in a 30km radius around broken reactor 4. It still remains in place today. In the days that followed the explosion, a number of volatile fission products escaped in to the atmosphere. Iodine 131, in particular, caused significant problems in the aftermath of the disaster. Large quantities settled in the ground and grass, and subsequently, in the food chain.

But Iodine 131 has a short half-life of eight days. It decayed and disappeared in about three months (ten half-lives). This has contributed to a general decrease in radioactive levels within the exclusion zone. However, there are still important hotspots of radioactivity, and not only in the direct vicinity of reactor 4.

"In the end, all the volatile radioactive elements will decay and disappear just like Iodine 131, it is just a question of time", Richard Wakeford told IBTimes UK. "But major radioactive fission products are still there 30 years after the explosion and they will stay for many more years. We can say that, overall, radioactive levels are not extremely high any more, but that is not the case everywhere, and some parts of the zone are and will remain dangerous."

He mentions Caesium 137, which has a half-life of thirty years. This means that only half of it is now gone, and will only disappear completely three hundred years after the disaster occured. The problem? Caesium 137 is responsible for "ground shines".

"As Caesium settles in the ground, it emits gamma rays which can go through people's bodies and remain in their tissues. This damages their DNA and potentially leads to the development of malignant tumours if DNA repair mechanisms fail to work", says Wakeford.

Future interventions near Chernobyl will have to take this health hazard into account in order to continue protecting workers and visitors in years to come.

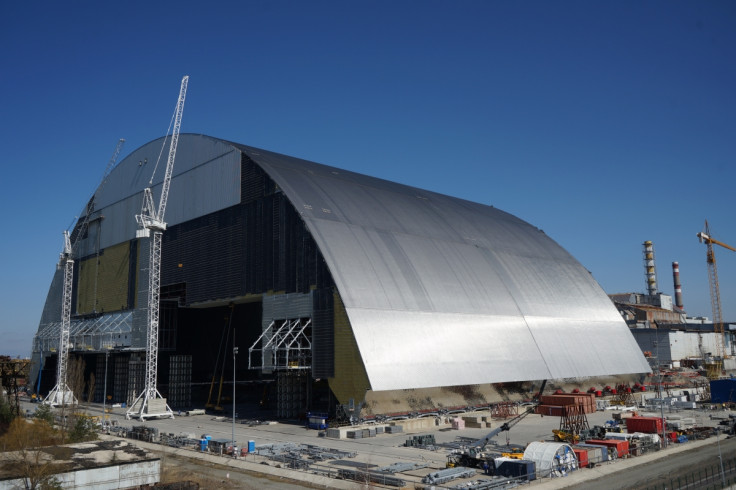

Chernobyl's future with the New Safe Confinement

In the wake of the disaster, the decision to isolate the damaged reactor under a massive steel and concrete structure - "the sarcophagus" - was taken. Designs for the constructions started as early as May 1986. This protective building, also know under the name "shelter" was only intended to be temporary. It was constructed under great urgency, and was particularly vulnerable to degradation and corrosion. In 1997, international and Ukrainian experts devised a new strategy for the conversion of this shelter in an environmentally safe system for the years that would follow.

The most significant decision was to replace the sarcophagus with another structure, called the "New Safe Confinement". Funded by the European Bank for reconstruction and development (EBRD), the projects aims to isolate reactor 4 under a large structure, 110 metres high and 165 metres wide. It has been designed to last for 100 years and is reportedly resistant to temperatures (between -43°C and +45°C), a class three tornado and a six Medvedev-Sponheuer-Karnik -scale earthquake. The structure is due to be completed in 2017.

"The aims of the new safe confinement are straightforward. First, it is to isolate the reactor more permanently, to protect people and the environment. Second, it is a stepping stone to start dismantling the reactor and manage all future potential operations of getting rid of nuclear fuel and radioactive waste" Vince Novak, Director of Nuclear Safety at the EBRD, told IBTimes UK.

A large crane system has been included to support the long term dismantlement of the sarcophagus and the reactor. It can be remotely controlled from afar, and allows experts to monitor what is going on inside the structure.

When the decision to replace the sarcophagus was taken, many ideas were evoked. There has been some criticism of the project, with most critics recommending a more simple approach.

"An option could have been concreting everything so that it became a monolith, then digging a huge pit, putting an enormous cube in there and covering it with earth. Seems elegant and effective, and there'd be nothing on the surface", Alexey Breus, a former operator at Chernobyl nuclear plant, told IBTimes UK.

However, those responsible for the project say such strategies are risky. "There has been about four hundreds ideas about what we should do and how. Covering the structure with concrete was one of them, but the problem is that this does let us monitor the reactor properly. We would be leaving its fate to chance", Novak says.

How to get rid of radioactive waste and fuel?

Another criticism is that the new safe confinement plans to protect the environment for 100 years, but does not come up with immediate solutions to address the problem of getting rid of the radioactive fuel. The confinement merely isolates it, leaving it up to future generations to solve the problem.

"The new confinement is a set dressing. As an acquaintance of mine, a Chernobyl expert who's died, used to say, it's a Hollywood film set designed to cover the problem, but not to solve it. It changes nothing. It doesn't solve the problem of the remaining nuclear fuel inside the sarcophagus", Breus points out.

Yet, the argument of those working to secure the former power plant is that the New Safe Confinement will in fact give them the breathing space they need to come up with new approaches for getting rid of the radioactive waste.

"Along with the safe confinement, an Interim Spent Fuel Storage Facility is also being built to store fuel from reactors 1 to 3. All of this is buying us time, before taking a final decision regarding how we deposit of it all. Where this waste will go is a question that still has to be answered, in the context of a national strategy. But I am confident that the right technologies will be developed to help us in the future", Novak says.

The current solutions being implemented will not solve all of Chernobyl's problems. However, it is a step forward, in making sure the situation does not worsen for the next generations.

"The New Safe confinement is a limited solution as regard to the general environment, it won't reduce radioactive levels or enable people to return in the exclusion zone. But you cannot have a damaged reactor lying around, something had to be done. It offers some protections, even if more questions will have to be answered in coming years" concludes Wakeford.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.