Canis lupus: We may be creating a new species of human-dependent wolf

Gray wolf populations in Europe and North America are doing well as they live in close proximity to cities.

As the human population grows and urban areas become ever more expansive, our settlements are coming into closer contact with large carnivores such as wolves, foxes, dingoes and bears. The gray wolf appears to be adapting to this particularly well and is thriving in many areas of Europe and North America.

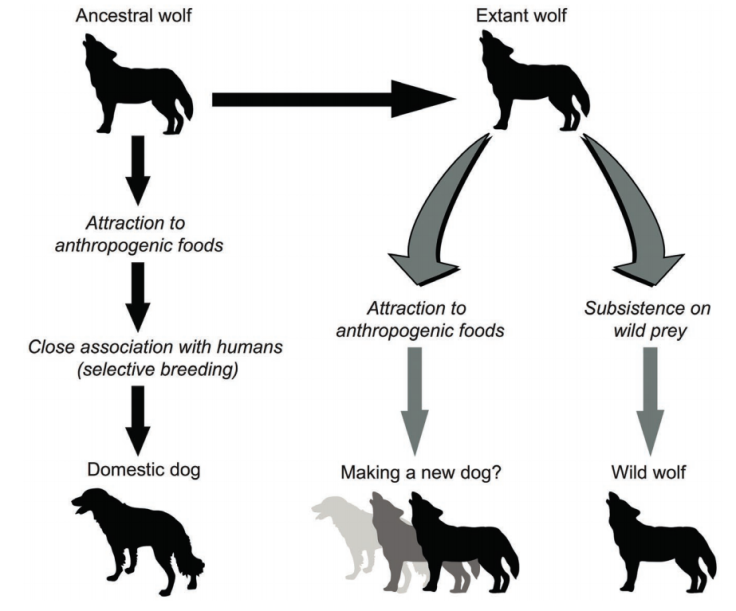

The authors of a study in the journal BioScience raise the question of whether this close interaction between humans and dogs is creating the right conditions for a new species of human-dependent wolf to split off from the wild gray wolf.

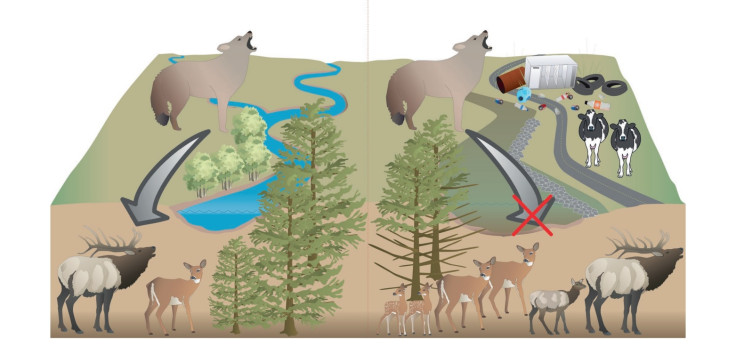

Separate populations of a species that rely on different kinds of resources can often be a precursor to reproductive isolation – in other words, the formation of a new species – study author Aaron Wirsing of University of Washington told IBTimes UK.

"In the very, very long term there is certainly the possibility that you would get certain populations of gray wolf that rely on human resources becoming isolated from wilder populations that rely on natural resources," said Wirsing.

This, if it happens, is likely to be a very long way off. But behavioural and social changes among gray wolves are already well underway. These changes played a role in the original domestication of wolves and the origin of dogs, Wirsing said.

"The dependence of wolves on human settlements led them to lose their fear and avoidance of humans and eventually develop an association with people. This set the stage for humans to domesticate wolves."

A 'new dog' would be more likely to come about by direct human intervention – however inadvisable this may be – rather than gentle genetic drift and isolation over thousands of years, said Claudio Sillero, a conservation biologist at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the research.

"Some crazy people in Europe and the US that are trying to cross dogs with wolves and they keep those animals as pets, although it's illegal in many countries," said Sillero.

The slower kind of speciation event separating human-dependent gray wolves from independent, wild gray wolves is not likely to happen any time soon if it happens at all, he said. There are several factors that stand in the way of such an event, such as the fact that wolves have a great range and so those that interact with humans and those in the wild will often come in contact with one another. Even within a single group of wolves, there is likely to be a range of behaviours.

"Some individuals in a group might profit from killing and eating livestock while others don't," said Sillero. "It's not a simple process where some will hang out with humans and become tamer, and others stay out in the wild."

But some evolutionary diversification between different gray wolf populations may arise because of dependency on human resources, he added.

"If you allow a few thousand years to go by there might be speciation – but it is not a given that we are approaching the dawn of a new dog."

Even without speciation, the development of an 'urban wolf' that is still the same species as the wild gray wolf is much more probable, Wirsing said.

"I think it's quite likely. It's already happened with coyotes. We have a conception of wolves as a creature of the wildness and of the coyote as much more of a generalist. But wolves are like that because we made it so, driving them away from urban spaces."

But all a wolf needs to live is food and space, he adds, and human settlements are already providing those to many gray wolves.

"In the very near future, not in terms of evolutionary change but behavioural flexibility and adaptability, I have little doubt – if humans tolerate it – that we'll see wolves expanding into agricultural areas and the outskirts of cities."

This is what will determine wolves' future alongside humans. Although humans might provide abundant resources in terms of food, relying on it can be a mixed blessing for wolves, Sillero said.

"Living next to humans is a hazard. Humans are likely to kill wolves, by running them over in a vehicle, trapping them, poisoning them – it's not a win-win situation to live close to humans."

But there appears to be a shift in attitudes among many farmers who would historically have killed gray wolves, he said.

"It's partly due to financial incentives and partly due to a generational change, but farmers are becoming less adamant in their aggression or the pursuit of wolves. And wolves are also getting wilier."

In terms of wolf populations, Sillero said, this is great news all around.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.