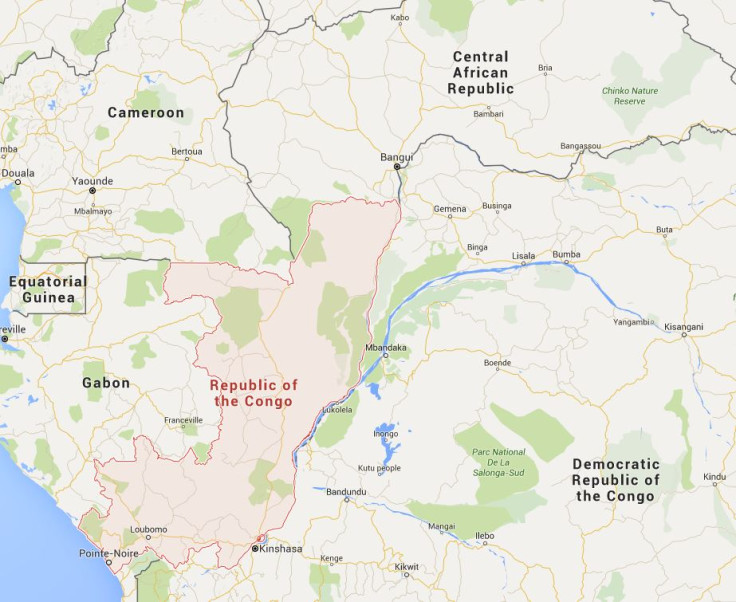

Congo-Brazzaville: Why is yet another African state descending into chaos?

Formerly called the French Congo post 1882, today's Republic of the Congo (also known as Congo-Brazzaville) was declared independent from the French in August 1960.

Although it has been relatively stable since the Second Republic of the Congo Civil War (1997-99), trouble started brewing in March 2015. President Denis Sassou Nguesso – one of Africa's longest-serving leaders – announced he wanted to hold a referendum to modify the country's 2002 constitution, which would allow him to run for a third consecutive term in office.

Similar stories have played out in a number of African states, and following the referendum in October last year, constitutional changes allowed Sassou Nguesso to stand in the March 2016 presidential election, a move condemned by the opposition as a constitutional coup.

Second Republic of the Congo Civil War

Sassou Nguesso's reign has been marred by claims of corruption and violence. Initially gaining power three decades ago, the general lost the top seat in 1992 following the country's first multi-party elections, which saw Pascal Lissouba become the nation's first ever democratically elected president.

During the mid-1990s, Sassou Nguesso, Lissouba and opposition leader Bernard Kolélas each formed a militia – known as Cobra, Cocoye and Ninja, respectively – drawing fighters from the politicians' ethnic and political backgrounds.

Lissouba's government was aided by president Laurent Kabila of the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo. Four months after the conflict erupted, Lissouba named Kolelas prime minister and his Ninja rebels officially sided with the government.

Violent clashes erupted between the factions in the run-up to the 1997 elections, and democratic advances were shattered when Sassou Nguesso and Lissouba began a bitter battle for power.

Unsuccessful talks ultimately prompted the civil war that left between 13,000 and 25,000 dead, with 200,000 internally displaced and 6,000 civilians seeking refuge outside the nation's borders.

Sassou Nguesso's three terms

France and Angola sided with Sassou Nguesso, who also attracted a number of Rwandan Hutu fighters and, with the Angolan intervention, Sassou came out victorious in October 1999. Commentators often highlight how he continued to work closely with a number of Western powers, notably the US and France, and allowing their firms to explore and extract Congolese oil.

His renewed reign was also marred by political repression, and in 2002, he took the top seat with almost 90% of votes and extended his term to seven years when a new constitution came into force. The president was re-elected in 2009 in a poll which the Congolese Observatory of Human Rights described as fraudulent.

Backed by the Congolese Labour Party, Sassou Nguesso, having secured consitutional changes which allowed him to remove age and term limits that would prevent him from standing again, the leader won his third mandate last month. Opposition leaders called for civil disobedience after rejecting the election they said was marred by irregularities.

At the end of March, a general strike was largely observed Brazzaville's southern districts, opposition strongholds, but ignored in the capital's north, where the president finds his greatest support.

The head of the Constitutional Court, Auguste Iloki, published final election results on 4 April, showing that Sassou Nguesso won with 60% of vote, followed by challenger Guy Brice Parfait Kolélas (15%) and Jean-Marie Michel Mokoko trailing with 14%.

First significant outbreak of violence

The announcement was preceded by a significant outbreak of violence in the oil-producing country in which 17 people died after clashes erupted between government forces and so far unidentified gunmen.

Sources described dozens of panicked people fleeing the capital's restive southern Makelekele and Mayana districts towards the north, with two police stations were allegedly set ablaze.

Government spokesman Thierry Moungalla later told Reuters that former Ninja militiamen were behind the attacks, but leaders of the opposition rejected the allegations, describing how hundreds of police and troops, some in armoured vehicles had invaded the city's southern areas in a "warlike operation".

Ilaria Allegrozzi, Amnesty International's Central Africa Researcher told IBTimes UK the organisation was still "collecting information to identify the perpetrators of the violence".

"What is clear is that we don't know what type of abuses were committed, but we recently denounced widespread arrests following the presidential elections and the fact that many have been illegally detained and harassed – including a number of members of the civil society, journalists and members of the opposition parties," she explained.

"For the next few days, we are going to keep monitoring the situation, get a better understanding of what is going on and look into any excessive use of force by police that was deployed across Brazzaville".

On 5 April, Andréa Ngombet, a young Congolese citizen in Paris and founder of Sassoufit – a collective representing Congolese civilians behind the protest movement – told IBTimes UK his group was on the international stage to ensure Sassou Nguesso sat down at the negotiating table, or intervened to end the crisis.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.