Could the South China Sea dispute trigger a Sino-US war? Five charts that tell you who might win

Beijing's sabre-rattling in the west Pacific has brought conflict in Asia closer than for decades.

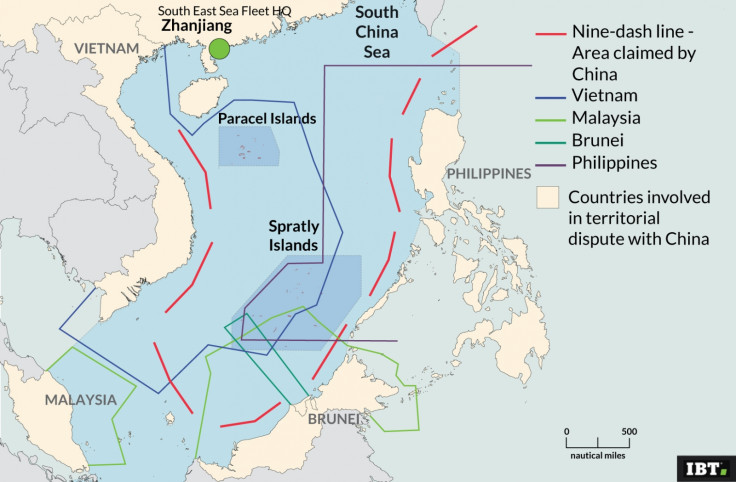

Chinese expansion in the South China Sea is bringing conflict between Beijing and its neighbours – Japan, South Korea, the Philippines and Vietnam – closer than it has been for decades. Vietnam has fortified several islands it controls, while Japan has been publicly rebuked by Beijing over its 'interference' in the sea – most of which China claims. The Philippines has called for "restraint and sobriety" as its own dispute with Beijing rumbles on.

But the South China Sea and a lesser-known spat with Japan over islands near Taiwan has not only brought talk of a regional war in the Pacific to the fore, but raised the prospect of the US being dragged into open warfare with China. Beijing's expansionism threatens not only the interests of US allies in East Asia but also global trade, given that some 40% of all shipping passes through the disputed area of ocean.

"As horrific as a Sino-US war could be, it cannot be considered implausible," warned the authors of the RAND Corporations August report, War with China: Thinking through the Unthinkable.

China and the US remain each other's largest global trading partners and have co-operated on high-profile deals such as ratifying the Paris Climate change agreement while in Hangzhou. In his comments during the announcement of the deal, US President Barack Obama said: "Where countries like China and the United States are prepared [...] to lead by example, it is possible for us to create a world that is more secure, more prosperous and more free."

But in reality US-China relations have been strained for some time, as demonstrated by the scrutiny of Barack Obama's visit to Hangzhou, where American reporters scuffled with Chinese security staff and Beijing was widely accused of snubbing the US president on his final international visit. Chinese hacking of US companies has been widespread, leading to America's indictment of five senior Chinese army officers in May 2014.

Meanwhile in the South China Sea and East China Sea, Chinese expansion has come at the expense of major US allies, including Japan. Japan's ownership of the Senkaku Islands, north of Taiwan, is enshrined in the US-Japan Treaty that was signed after the end of the Second World War. China's increasingly hostile stance towards its neighbour over the islands risks dragging the US into a conflict between Beijing and Tokyo.

This is especially problematic given China's claim of a 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) outside its borders, an area that the US interprets as "international waters". In June, China began sending ships and aircraft to patrol the EEZ, risking a skirmish between the American warships that already patrol the zone. In the East China Sea, Japan and China's claims overlap – raising the prospect of a low-level clash that could easily escalate.

Although admitting that a conflict between China and the US is "unlikely", the RAND Corporation postulated a number of scenarios about how a war would begin and how it would play out. The most likely is that a small skirmish between ships or aircraft in either the South China Sea or East China Sea would provoke a larger conflict between China and one of its neighbours, and the US would be forced by treaty obligations to enter.

"A war between the US and China would be regional, conventional, and high-tech, and it would be waged mainly on and beneath the sea, in the air, in space, and in cyberspace [...]. Unless both US and Chinese leaders decline to authorise their militaries to carry out their counterforce strategies, the ability of either state to control the ensuing conflict would be greatly impaired. Both would suffer large military losses," it said.

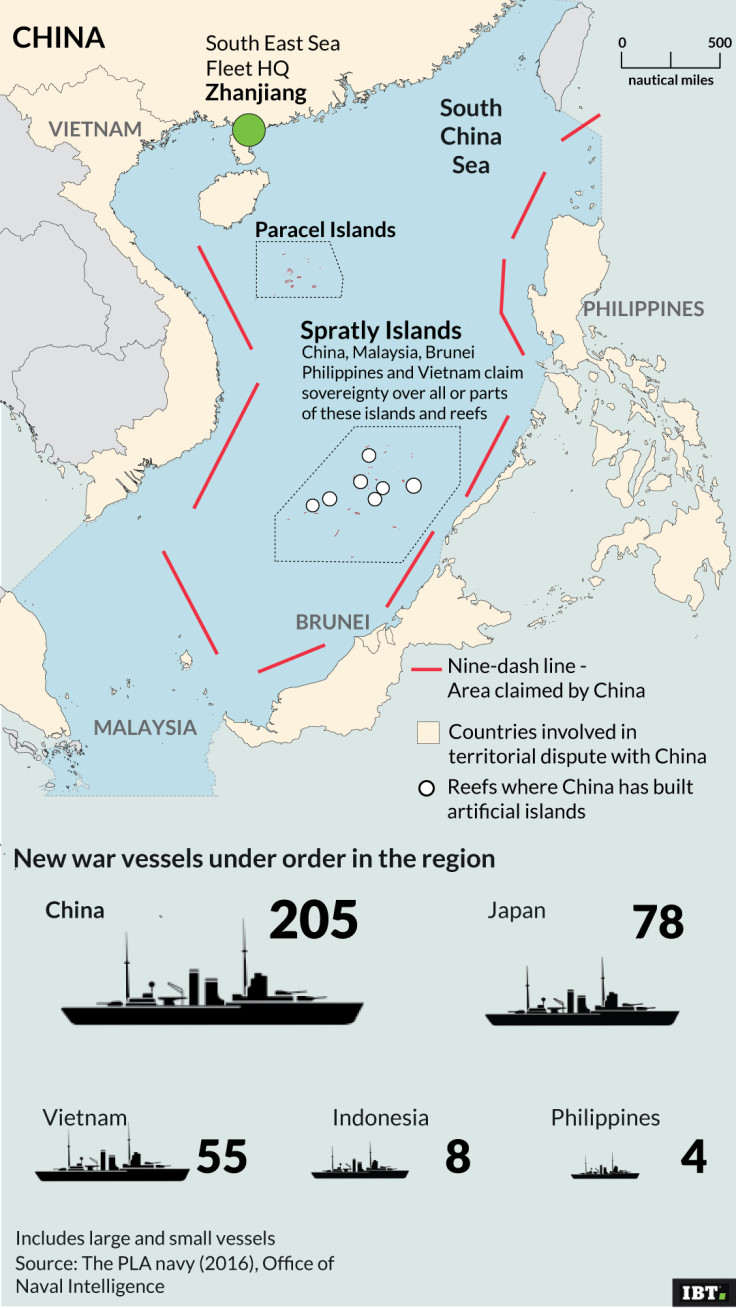

Compared to its Asian neighbours, China has a clear military advantage. It has 205 vessels in the South China Sea compared to Japan's 78 and Vietnam's 55. It also has four nuclear ballistic submarines in its South Sea Fleet at Zhanjiang and a further five nuclear subs between there and Qingdao, its northern naval hub. Its South Sea fleet is by far the best stocked militarily of its three naval hubs, with a total of 121 units.

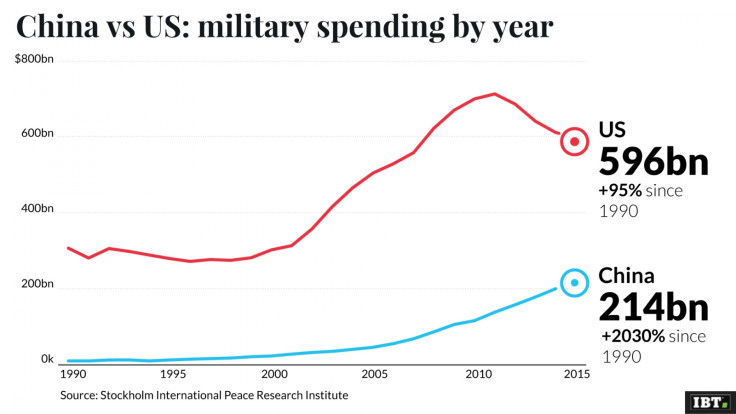

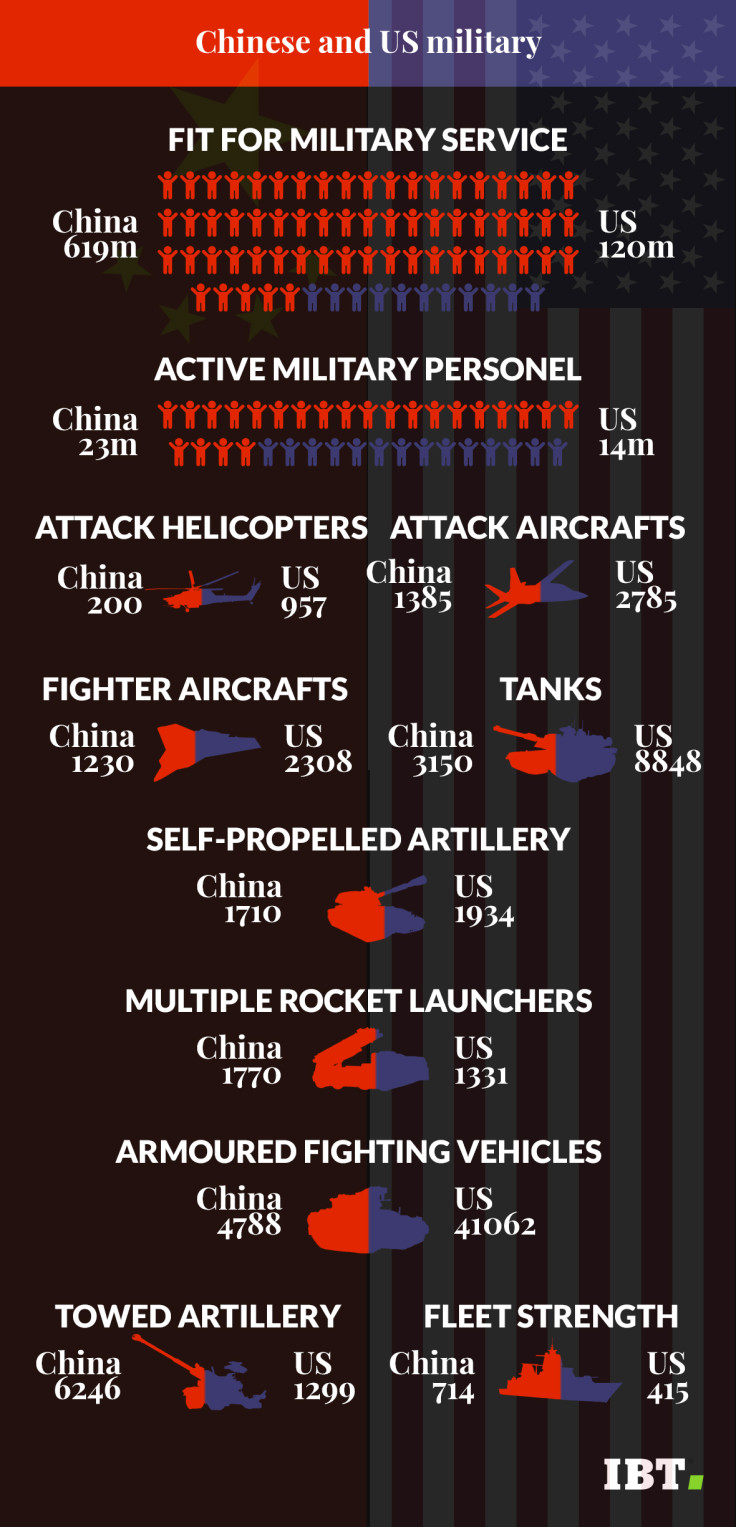

Compared to the US, China has a huge reserve army of some 619 million soldiers compared to America's 120 million, but given that a conflict between the two would be unlikely to involve ground forces, it is naval and airborne military resources that are more relevant. The US has vastly more fighter aircraft than the Chinese (2,308 to 1,230) and spends far more per year on its military, $596bn in 2015 compared to $214bn in China.

But RAND points out that while as of 2015 the US would have the upper hand militarily, by 2025 that gap could have shrunk as China pours more money into developing its military arsenal. While Chinese military spending is dwarfed by the US, it has been increasing at over 2,000% since 1995 compared to 95% over 25 years in the US. That said, the last time China fought an actual war - barring territorial skirmishes - was in 1979. The US has fought at least two full-scale conflicts since 2001.

In terms of economic impact, RAND suggests that China would suffer more from the conflict than the US, with much of the Western Pacific – its key trade route – becoming a war zone. Beijing would lose other allies – such as Europe – that would be likely to back Washington. All in all, RAND estimates that China would lose between 25% and 35% of GDP in a war with the US.

The likelihood is that while China will continue its sabre-rattling in the South China Sea, it is unlikely to push its neighbours so far that a regional war could break out and trigger a Sino-US conflict, but experts increasingly urge both Washington and Beijing to be aware of the costs – if only to deter them further from provoking a conflict that neither side wants.

Nevertheless, in the short term RAND's advice to both sides is clear: if you want peace, prepare for war.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.