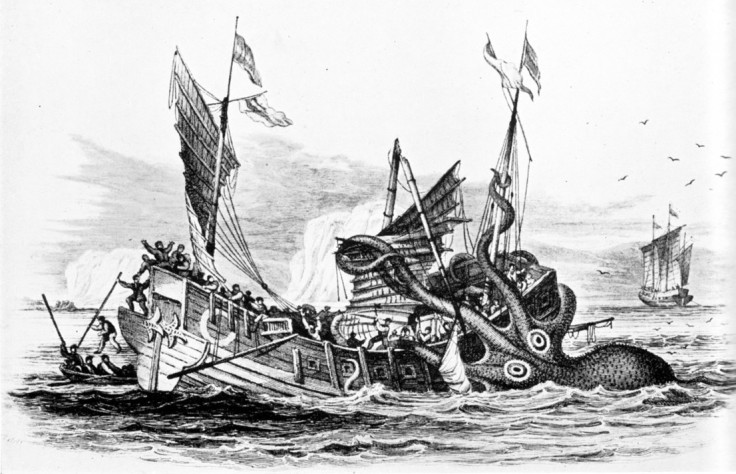

Does an arrangement of nine fossilised Ichthyosaur remains prove the Kraken's existence?

The Kraken has caused sailors and pirates fear since the 13<sup>th century, but evidence for it so far has been word-of-mouth. However, in 2011, scientists discovered circumstantial evidence that the mythological ocean-dwelling beast could have in fact once been real.

It had long been thought that ichthyosaurs of the Triassic period, known as Shonisaurus popularis, were the top of the food chain in their day some 215 million years ago. The large marine reptiles could grow up to 15 metres and were one of the most ferocious predators of the ocean at the time.

In the 1950s, Charles Camp of UC Berkeley wrote about the remains of nine ichthyosaurs in the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada. However, the site has confused scientists since its discovery.

"Charles Camp puzzled over these fossils in the 1950s," said Mount Holyoke College palaeontologist Mark McMenamin, who presented his work at the Geological Society of America in 2011. "In his papers he keeps referring to how peculiar this site is. We agree, it is peculiar."

After long deliberation, Camp concluded that the ichthyosaurs probably became stranded in shallow waters or that they had eaten toxic plankton. However, more recent work from the site suggests that the waters they died in were deep and that, in fact, that the animals didn't die at the same time.

"I was aware that any time there is controversy about depth, there is probably something interesting going on," said McMenamin. "It became very clear that something very odd was going on there. It was a very odd configuration of bones."

Furthermore, McMenamin believes that the bodies had been rearranged posthumously. "Modern octopus will do this," he said. From this he theorises that an ancient, large octopus – much like the Kraken – could have been the culprit. "I think that these things were captured by the Kraken and taken to the midden and the cephalopod would take them apart."

However, could an octopus have taken down such large predators? Yes, is the short answer. Several years ago, the Seattle Sea Aquarium set up cameras in its large tanks after it noticed that sharks had been dropping dead.

What they discovered was that an octopus had been killing them, essentially eliminating the threat before the sharks came for it. "We think that this cephalopod in the Triassic was doing the same thing," said McMenamin. The fossils showed signs that their necks had been twisted or their ribs broken.

McMenamin goes onto say that there wouldn't be evidence for the large cephalopod because they are soft-bodied, meaning that they wouldn't fossilised. He notes that the evidence is purely circumstantial, but that he is prepared for doubters. "We're ready for this," he said. "We have a very good case."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.