In focus: How Detroit is rising from the ashes

Detroit is a city in flux. Its journey from motoring powerhouse to bankruptcy, and lately to regeneration, has been neatly summed up by a local tour company that has entitled one of its city walks: rise, fall and renewal.

This description is also embedded into Detroit's very fabric; iconic buildings that were once symbolic of a vibrant economy before becoming vacant and left to rot are being bought up and renovated in increasing numbers. Alongside investment from billionaires are small businesses, start-ups and a flourishing art scene that are all contributing to Detroit's new lease of life.

But as the city attempts to recapture the success enjoyed in its heyday, when Motown and mass car manufacturing put Detroit on the global map, a tale of two Detroits is emerging.

What went wrong?

The decline of the automobile industry, a falling population, high levels of borrowing and inefficient tax collection were just some of the reasons given for the $20bn (£12.9bn) black hole in Detroit's finances that led to the biggest municipal bankruptcy in American history in 2013.

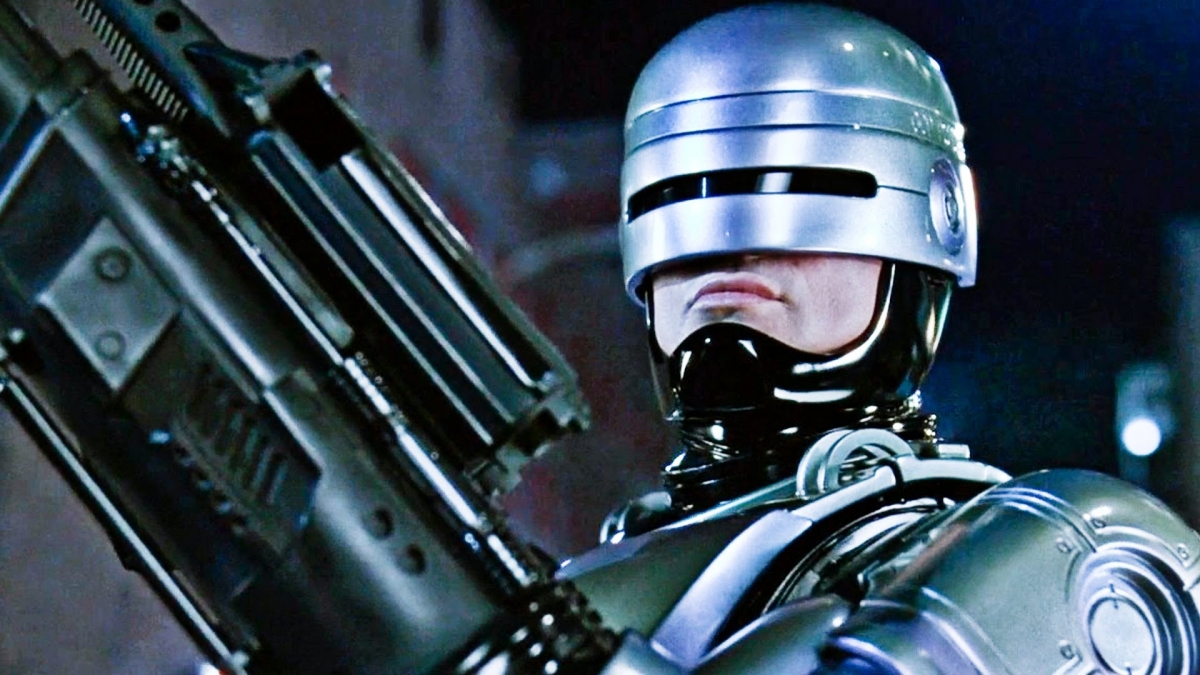

The city continues to bear the open wounds of the disaster on its streets. Thousands of abandoned buildings and neighbourhoods, unlit roads and rotting cars, emblematic of dystopian urban decay on a grand scale. Over 84,000 wrecked structures and vacant lots remain and, according to the Detroit Removal Task Force, cleaning them up could cost $2bn, money it does not have.

Beyond the external scars the buildings wear, their internal emptiness is illustrative of Detroit's biggest problem. Its population stood at 1.8 million in 1950 and the city was built in anticipation of population growth. Instead, it has declined dramatically and now stands at 700,000. An average of 2,000 people left every month between 2000 and 2010 and anyone walking through Detroit will be struck by just how empty the streets have become.

The only way for the city to recover is by repopulating it with tax payers, and last week mayor Mike Duggan claimed that people are beginning to come back.

"This city is on the high road and we want the rest of the world to come here and see it, everybody in the world has a soft spot for an underdog. We are seeing, for the first time, people coming back."

Duggan knows that employment and investment are the best ways to attract large numbers back, and this has started to flow.

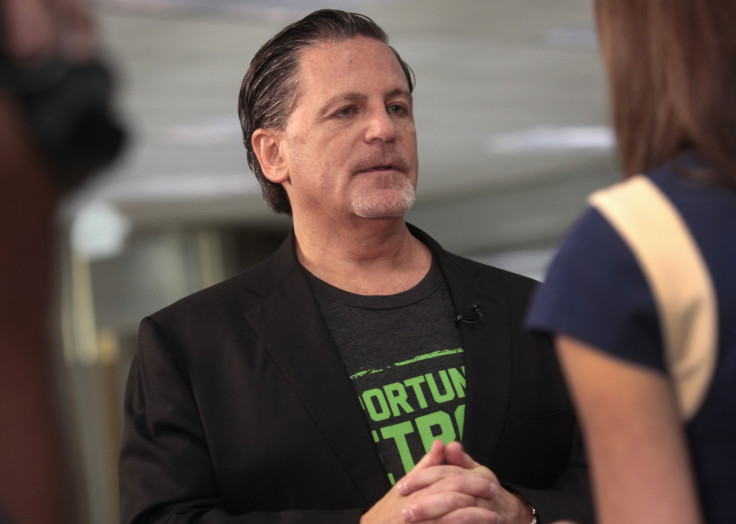

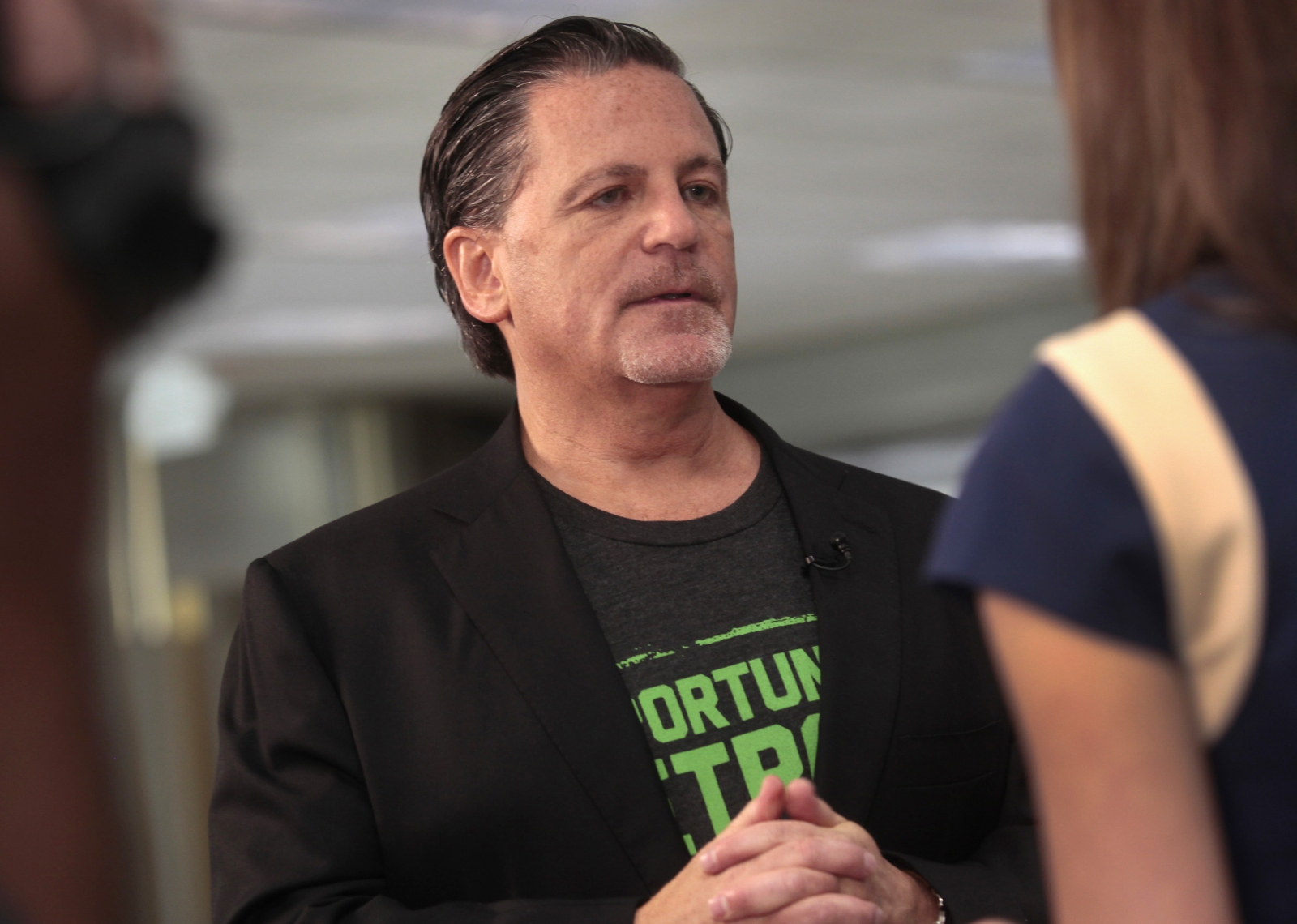

Dan Gilbert

Investors, convinced that they are buying at the bottom in anticipation that the only way is up, have been snapping up real estate at rock bottom prices. Dan Gilbert, a Detroit born billionaire, has become the poster boy of such investment. Hailed as Detroit's saviour in some quarters, he has pumped $1.7bn into buying up 70 major buildings and has promised to restore several to their former glory.

Quicken Loans, the mortgage firm Gilbert owns, has moved thousands of employees downtown and the tycoon is now encouraging other businesses to follow suit through his "Opportunity Detroit" scheme.

Speaking last week to an audience of entrepreneurs, Gilbert spoke of his vision for the city. "We have to create an environment, a garden for small businesses to grow. It's hard to go to New York and make a splash, and we use that as a sell line. Here you can impact a great American city."

There is no doubting that Gilbert's money has helped rejuvenate parts of the city, and Detroit desperately and visibly needs investment that the local authority cannot provide. But Gilbert's involvement is not without controversy. Investigative journalist Steve Neavling has uncovered a string of uncomfortable issues ranging from Gilbert's extensive use of CCTV cameras to donations to Duggan's mayoral campaign. Perhaps most damningly, Neavling points to Gilbert's alleged role – by issuing "improper mortgages" – in helping cause the property blight Detroit has suffered from.

Last week billionaire Richard Branson also got in on the act, travelling to Detroit to celebrate Virgin Atlantic's new route from London. He aims to attract business travellers, pointing to the changing picture of the city.

"Detroit is beginning to boom again and we want to play our part in helping the mayor make this city great again."

Gentrification

Parallel to Gilbert – and sometimes in conjunction with him – trendy cafes and restaurants have been springing up in increasing number as budding entrepreneurs enjoy cheap rents and low start-up and staffing costs.

In the last year alone, 30 restaurants have opened up and Detroit is now home to the highest concentration of designers in the US. There are also 1,300 urban community farms that produce enough fruit and vegetables to supply 20% of the city.

Art is also flourishing. The Heidelberg project, designed to improve peoples' lives through art, is just one of a number of creative initiatives. Murals, graffiti and street art are spearheading Detroit's beautification.

The city is now seen as on its way to gentrification and, ultimately, resurrection.

Poverty

But this rebirth has been limited to specific pockets of the city, such as the riverfront and downtown. Residents in peripheral neighbourhoods, who are poorer by almost every barometer, have seen little benefit.

The most stark illustration between the two Detroits is to be found in public services and policing. Detroit has the highest murder and violent crime rate of any major city in the US and wealthier business owners and neighbourhoods often club together to bankroll private police forces. Those in poorer neighbourhoods have to make do with the city's overworked law enforcement agencies that can sometimes take hours to respond.

Most recently, the city has even started cutting off the water supply to thousands of homes that cannot afford to keep up with bills.

Duggan surmised the issue of public services when he became mayor in 2014. "How do you deliver service in a city where the unemployment rate is double the state average, and we've got to rebuild a water system and a bus system and a computer system and a financial system?"

His answer has been to allow private investment take root in the hope that Detroit can raise enough tax dollars to eventually be in a position to provide services.

Any other city

Large scale disparities in wealth and services are not unique to Detroit; most major cities function in a similar manner.

As well as the increased tax-take the city stands to reap from investment, proponents of the kind of change Detroit is witnessing argue that with parts of the city improving, it will have knock on affects for the poorer neighbourhoods in time.

But unless there is a conscious effort to ensure that this happens, rather than an assumption, Detroit's revival will simply add to the polarisation, and it will in fact only be a renewal for the few and not the many.

Detroit picture gallery:

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.