Harry Leslie Smith: 'Appalling Calais refugees camp reminds me of war-torn Hamburg in 1945'

At the refugee camp in Calais, walking amid the tents and torment as winter approaches, Harry Leslie Smith is taken back to a place he had been 70 years before. Smith, 92, was stationed in Hamburg with the RAF as a wireless operator at the end of the Second World War.

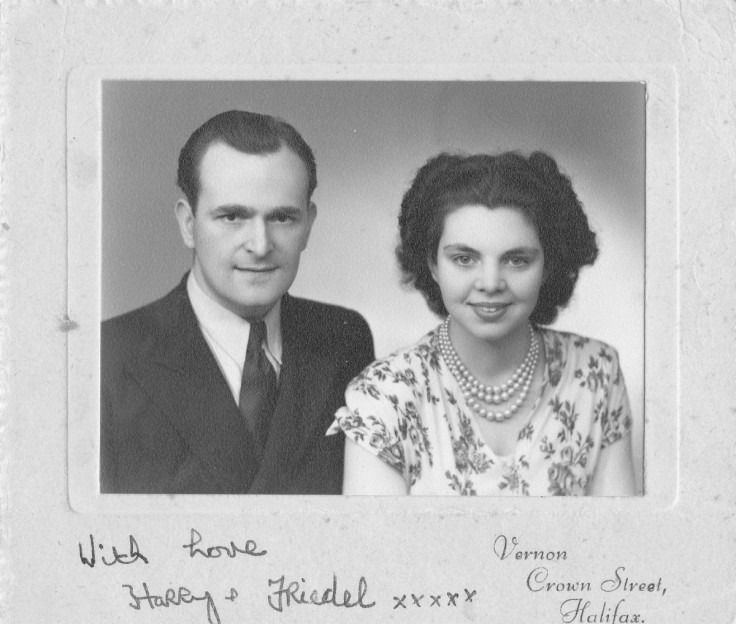

In his new book, Love Among The Ruins, Smith tells his story of life in 1945 Hamburg, where he met his soon-to-be German wife, Friede. The dystopian city Smith describes was smashed and shattered by Allied bombing. Its struggling residents left to beg, borrow and steal to survive under occupation by the British and Americans. The Allies, themselves broken and impoverished by war, could only offer measly food rations.

"It was the first time I saw millions of refugees, streaming through Hamburg," Smith tells IBTimes UK. "It was the first time I saw a camp of refugees there, and it stretched for field, after field, after field all little shacks built no bigger I would say than 6ft by 6ft, made of metal strips, panels, wood that had been picked up. There was no shortage of that because of the bombing of Hamburg.

"There must have been at least 5,000, 6,000 people in this, and it was all arranged in streets, and spaces between the streets. It was pathetic. They were also starving, as were the rest of the German people at that time, because the Brits were allowing them 1,200 calories a day, which was hardly sufficient to keep them alive.

"Because of the bombing, which really I would say 30 to 40 square miles of Hamburg city was devastated with huge mountains of rubble, it was just a tragic scene. Before I went to Hamburg, my thoughts of the Germans was black-booted soldiers scrambling across Europe. I had no great love for them.

"But once I crossed that border, I realised that all civilians are at the mercy of their leaders and they suffer just as much as people they were attacking themselves. I saw children in Germany who were starving just as much as they were in Holland. I saw children living in the huge mountains of bombed rubble and it was almost primitive.

"I was in Calais last Tuesday (3 November) at the refugee camp there and it brought it all back to mind... I am absolutely horrified that Britain and France can allow people to live in such horrific circumstances. I was just completely appalled."

While living in Hamburg and watching the suffering all around him, Smith developed sympathy and pity for the citizens of a country he had been at war with for six years. He soon met Friede and wooed her by pinching RAF supplies to give to her family to help them survive the grueling post-war poverty now engulfing them. Despite a number of barriers to their relationship, including a wartime law against marriage between Britons and Germans, it survived − just as they both had. Smith had ground through squalor and utter poverty during the Great Depression in the north of England, coming out the other end, while Friede had fought her own battles with her illegitimate birth, relentless bombing raids and ominous Nazi suspicions about her racial origins.

Eventually, the marriage rules were lifted and the pair were allowed to wed in 1947. But did Smith's sympathy for the war-ravaged German people, and his new German wife, generate any hostility from friends and family back in England? "I think the main criticism I got was from my own mother, who thought I was a traitor marrying a German," Smith says. "I took no notice of her because we didn't have a very good relationship anyway. That didn't bother me. And when we returned to Britain, I came before my wife because I was sent to the airport in Manchester and I had to wait four months before I could get my wife to join me. But when she did finally get here and we moved back to Halifax, where I was living pre-war, I didn't sense any feeling that there was any enmity to the Germans. And it could possibly be because we had so many refugees.

"People don't realise that when the war ended in 1945, we had 300,000 Polish soldiers living in Britain that had to be taught English and accommodated, because they couldn't go back to their home, it was already under Russian control. And they were just one part of the refugee system that we took charge of. Britain handled it, and everyone was integrated into society without a great lot of hoo-hah that seems to be prevalent today when a refugee crisis occurs."

Love Among The Ruins is, by Smith's own admission, an intense and deeply personal memoir about the most important period in his life. The narrative of an unlikely love story is woven through vivid scenes of Hamburg in 1945 − the broken cranes, toppled buildings, black marketeers and unscrupulous Allied soldiers taking advantage − and broader political developments of the time. It is both autobiography and social history; a powerfully written catalogue of captivating memories at a pivotal moment in 20th century history.

The story ends at the start of the Smiths' long life together. Tragically, Friede died of cancer in 1999. It is obvious from the book just how much Smith adored her. It is even more so when hearing him speak about her passing, the rawness of the pain still clear from his voice even 16 years on. "I was absolutely devastated. I really couldn't believe it," Smith says. "She'd been in hospital for only a matter of a couple of weeks. And then the doctor told me she really didn't have much longer to live. So I arranged for a hospital bed to be delivered to my home, and had it put in front of the window there, and arranged for six nurses to be there for 24 hours to take care of her.

"The moment she died, I was at the foot of her bed, and stroking the lower part of her legs, and I said to her: 'You know, your legs feel pretty dry', and I said: 'Would you like me to put some cream on?' and she said: 'Yes please'. So I said: 'I'll just go to the bathroom and get what I needed,' and when I came back, I was about to put the cream on, and then I saw the blood running through her toes. And I knew that was the end. I'd seen it before. And I stood up, leaned over her, and she knew, she threw her arm around my neck and wouldn't let go.

"In 2000, I went back to Hamburg and saw a couple of her old school friends, talked to them a while, and then I went back to where she lived in the apartment and closed the door. I stood across to it, and tried to relive those days when I would wait for her to come out of the apartment door."

Smith emigrated to Canada in the 1950s and was a businessman selling Oriental carpets for years. But in retirement, and after the passing of his wife, he has had a renaissance as an author, social commentator and activist. In his nineties, he still addresses political rallies and is a fierce critic of the Conservative government, in particular its austerity programme, drawing on his own early experiences in the Great Depression for his powerful rhetorical critiques.

As the old adage goes, behind every great man is a great woman. Smith's devotion to Friede, and his life's successes, suggest it is more than just a tired cliché. "She was the best thing that ever happened to me," Smith says. "Honestly. She had something I never had. She had a bohemian outlook on life. She liked jazz and Goethe, and she finally got me back on track and made me a more civilised person."

Love Among The Ruins is published by Icon Books.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.