Hitler's death 70th anniversary: Who let Nazi war criminals escape to South America after WW2?

In November 1945, in the German city of Nuremberg, the first international war crimes trial opened. Three of the top Nazi leaders – Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler and Joseph Goebbels – had already committed suicide, leaving behind 21 defendants as key players in a system that had cost the lives of 50 million.

The responsibility of some was clear. Hermann Goering, a leading member of the Nazi Party, had ordered the organisation and coordination of the "Final Solution" to the "Jewish question". Joachim von Ribbentrop, the foreign minister of Germany, directed diplomatic efforts to persuade Germany's Axis partners to deport their Jews to Nazi killing centres.

Yet many of the key architects of the Holocaust were absent from any kind of trial, escaping justice for decades and in many cases, until death.

Many top Nazis fled to South America as Soviet tanks rolled into Berlin, never to pay for the atrocities they wrought across Europe. So why did so many war criminals escape to the continent?

Official reluctance

"Only a fraction of leading figures in the Nazi state were brought to trial at Nuremberg; 10 of the 24 accused were executed in October 1946," Dr Toby Simpson, of the Wiener Library, tells IBTimes UK. "Many other prominent Nazi figures – such as Adolf Eichmann who was later captured – escaped the Nuremberg trials, with many taking advantage of South America as a place to flee justice."

"In particular the Argentinian Peronist regime was sympathetic to Nazism, saw potential political advantages in assisting Nazi war criminals, and even went to considerable lengths to facilitate their escape and hiding," he adds.

"Argentina was not the only South American nation to harbour such men, however, and in this respect long-established cultural ties between the continent and European countries, including Germany, such as Roman Catholic religious networks, played an important role."

Historians have claimed that in both Europe and South America, government officials, police and the courts were reluctant to search for Nazi war criminals – leading many to evade justice. Assisted by a network of former SS members, Dr Josef Mengele, Auschwitz's "Angel of Death", fled to Argentina in July 1949, hiding in Buenos Aires before moving to Paraguay in 1959 and Brazil in 1960. Despite rumours of his whereabouts, he was never found – prompting historians to state that official reluctance prevented his capture.

Some, including German historian Daniel Stahl, have said Mengele was never caught because French police officers employed by Interpol had refused to carry out searches for war criminals because they were themselves Nazi collaborators. Although the German Justice Ministry advised the Federal Criminal Police Office to conduct a manhunt, without involving Interpol, Mengele was never found. It was discovered he had drowned while swimming off the Brazilian coast in 1979 and was buried under a false name – but his remains were positively identified by forensics in 1985.

Others historians have made similar claims. In his 2002 book The Real Odessa, Argentine researcher Uki Goñi used access to his country's archives to claim Argentine diplomats and intelligence officers, had, at the instruction of Juan Perón, encouraged Nazi war criminals to escape to the country.

Recent discoveries have revealed more damning evidence of official reluctance. In 2011, leaked German intelligence files published in the Bild newspaper showed that as early as 1952, the West German government knew where Adolf Eichmann – one of the top SS officers responsible for organising the Holocaust – was hiding in Argentina under the alias of Ricardo Clement.

"SS colonel Eichmann is not to be found in Egypt but is residing in Argentina under the fake name Clement." It added: "Eichmann's address is known to the editor of the German newspaper Der Weg in Argentina."

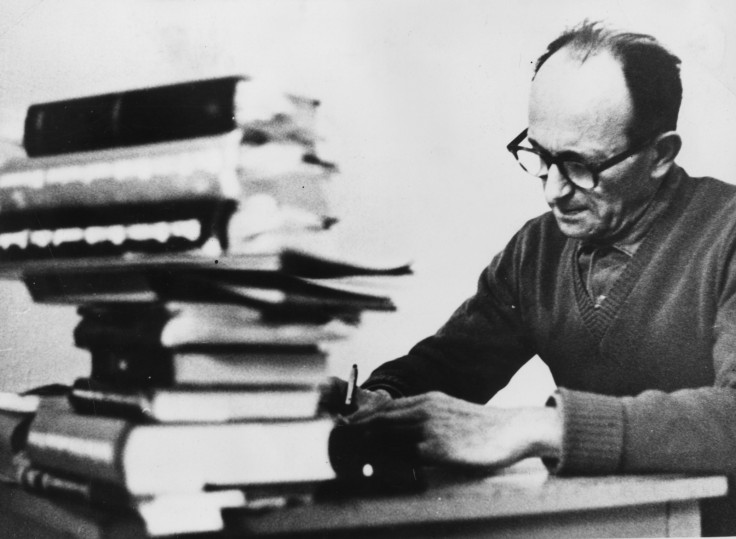

In 1960, Eichmann was tracked down by Mossad and flown to Israel, where he was convicted of crimes against humanity and hanged two years later.

Moral concerns and commercial ties

The chequered history of some South American states led to concerns over their own moral legitimacy, historians have also claimed. According to Stahl, this is the main reason why Gustav Wagner, the "beast" of Sobibor, evaded capture.

After the Second World War, Wagner was sentenced to death in absentia, but escaped with Franz Stangl, a fellow SS commandant of Sobibor and Treblinka, to Brazil. He was admitted as a permanent resident in April 1950 and issued a Brazilian passport in December, living under the pseudonym Gunther Mendel until his true identity was exposed by Simon Wiesenthal.

In the late 1970s, judges at Brazil's supreme federal court refused a request from the West German government for Wagner's extradition – stating alleged inaccuracies in the application.

In his book Nazi Hunt: South America's Dictatorships And The Avenging Of Nazi Crimes, Stahl claims West Germany's ambassador to Brazil at the time explained the Brazilian authorities were concerned Wagner's extradition would encourage opponents of the government to make demands that would compromise their authority. If they were to accept West Germany's request, all crimes in Brazil – even those committed by police and other officials – would have to be brought to justice.

Brazil also had commercial ties with Axis powers – namely Germany and Italy – before and during the war. The country has acquired German aircraft, weapons and armoured vehicles, also getting hold of licenses to manufacture some German-designed aircraft.

Argentina, the hiding place of various Nazi war criminals, also maintained close relations with Axis powers – although it officially remained neutral. The newly-elected president Ramón Castillo drew the country closer to the Axis and in 1942, Argentina approached Germany with a request to buy equipment, including weapons and aircraft. Ultimately, Castillo believed the Axis would triumph in the war – and Argentina only declared war on Germany in 1945, a month before it was over.

According to Simpson, Nazi sympathisers facilitated the escape of members of the SS to Argentina, Brazil and other South American countries. "Without the assistance of Nazi sympathisers from Europe, for example in Spain, Italy and Switzerland, it is unlikely a significant number would ever have successfully escaped Europe in the first place," he says.

"Efforts to bring escaped perpetrators of Nazi crimes to justice were generally not led by state diplomats, but rather by survivors of Nazi persecution in Europe, America and Israel who undertook the painstaking work of tracing perpetrators across borders."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.