Viktor Orbán and Hungary's dark path towards dictatorship

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been accused of destroying press freedom, attacking human rights and rewriting the history books. But could his popular 'illiberal' style of politics spread through the EU?

If there's a microcosm for what liberals in Brussels fear most about Hungary's future, it's Asotthalom.

A small village near the country's border with Serbia, it has a population of just 4,200 but has managed to make headlines across the world.

It was in November that its mayor, László Toroczkai, passed decrees prohibiting Muslims from wearing any Islamic garb in public and banning the opening of any mosque in the village.

In keeping with his right-wing nationalist Jobbik party's idea of "preserving Hungarian traditions", he went on to mimic Russian-style legislation by outlawing the "propagation of gay marriage" and public displays of affection among same-sex couples.

"No Muslims and no gays" effectively became the policy – punishable by fine – of a town in the heart of the European Union.

Were it not for the parallel actions of Hungary's radical right-wing government, Asotthalom would be dismissed as a blip on the continent.

But since Prime Minsiter Viktor Orbán's Fidesz party was elected to power with a two-thirds majority in 2010, it has been on a mission to kickstart what it calls an "illiberal" revolution to save Hungary from the EU - and even Europe from itself.

Inspired by the supposed successes of fellow illiberal states like Russia, Turkey, China, and Singapore, it's a mission that took centre stage during the height of the migrant crisis in 2015 when thousands of people fleeing conflict and poverty crossed Hungary's border into the EU.

In a speech rallying against the "crime and terror" he said migrants brought to Europe, Orbán ignored Brussels' open door policy and erected fences, built migrant camps and promoted the country's own volunteer border patrol militia.

"Today Europe is as fragile, weak and sickly as a flower being eaten away by a hidden worm ... the masses arriving from other civilisations endanger our way of life, our culture, our customs and our Christian traditions," he told a crowd of supporters.

Given the slowness of other EU leaders to react to the crisis – and their subsequent but now withdrawn open-arms policy – Fidesz supporters believe Orbán has been vindicated by his border protection policy.

But the Hungarian leader has gone beyond anti-mass migration in his blueprint for a new kind of nativist, populist and Christian Hungary, one that puts nationalist goals ahead of the cosmopolitan agenda of raising individual liberty.

Orbán, a former liberal who gained prominence nationally with his fight to rid Hungary of Soviet troops while in his mid-20s, has been accused of using his time in power to dictatorially remove the checks and balances of democracy.

Since being elected seven years ago, he has passed a swathe of laws centralising control over the media, education and civil society, while also installing allies in key positions in the courts.

It's just the beginning of what some political analysts in Hungary say is a long-term strategy to bring radical right wing politics back into Europe.

"If you go back to 2009, before Orbán returned to power, he said his idea is that he wants to create a so called central government force that can govern for 20 years at least," says Professor Péter Krekó, a political scientist and director of the Political Capital think-tank.

"And of course if you want to govern for 20 years you have to be an illiberal, you have to weaken the constitutional system, you have to silence your opposition, you have to break down the NGOs ... this is the price if you want to stay in power for 20 years."

It's a price that has led some of Orbán's more alarmed critics to claim the EU is watching its first dictatorship in the making.

It was a sentiment summed up at a 2015 EU summit in Riga, where a smiling European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker dispensed with diplomatic protocol to greet Orbán with a "Hello, dictator."

While Juncker made his remarks with a puckish smile, the first victims of many dictatorships – minority groups – say they are not laughing.

Suffering the fallout of this "revolution" have been small, under-financed NGOs, the often vulnerable people they try to help and the freedoms they try to protect.

Critics say a recent legal crackdown on foreign-funded NGOs has seen them branded "foreign agents", while an increasingly state-controlled media leaves critical journalists publicly maligned as "traitors". A relentless anti-Brussels advertising campaign by the government, meanwhile, tries to leave Hungarians with no illusion about who the "real" dictator is.

But the Fidesz government's supporters say the Hungarian people are finally being listened to, and hope this rapid restructuring of Hungary is just the start.

Despite governing a population of just 10 million people, Orbán's illiberal call to arms has reverberated throughout eastern and central Europe.

And he hopes it could pose a serious challenge to German Chancellor Angela Merkel's vision for the future of the EU.

Silencing NGOs

In what has become one of the more far-reaching of his government's reforms, Orbán has been accused of trying to silence his critics by demanding NGOs backed by money from abroad re-register as foreign agents.

Mimicking moves taken by Vladimir Putin in Russia, NGOs receiving more than €23,000 (£19,900) a year from foreign sources will have to identify to the public as an "organisation receiving foreign funding".

They will also have to disclose a list of foreign donors and be subject to further bureaucratic checks.

Orbán says the measures, passed on 13 June amid strong condemnation from Brussels, are needed to stop foreign meddling in the country's politics.

"Hungary cannot afford to allow organisations that remain in the shadows – not declaring who they receive their money from and for what purposes," he said in a radio address in February.

His Fidesz government also claims foreign-backed NGOs lack "democratic legitimacy" and are prone to money laundering.

But several human rights groups speaking with IBTimes UK have warned the move will lead to their campaigners being unfairly stigmatised and will have a chilling effect on civil society – one of the last free and critical voices they say is left in Hungary.

Goran Buldioski, director of the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE), which provides about €4m to around 50 NGOs in Hungary every year, even suggests Orbán's crackdown could spark a contagion, as other EU leaders eager to silence their critics do the same.

"It creates a precedent where other leaders – in particular Slovakia, Romania, Poland, to list just a few – may follow suit because they could see this as establishing a certain control of sovereignty in their countries," Buldioski tells IBTimes UK from his office in Hungary's capital, Budapest.

"My worry is first contagion – that the civil society space will shrink and will not be as open as it were. But I also have an additional worry. Today it's civil society – will other entities be next?"

It's a sentiment shared strongly by the European Commission, which began legal proceedings against Hungary over the NGO law last month.

Open Society has found itself centre stage in the row now engulfing the government.

Orban's so-called chief villain in his battle to supposedly protect Hungary from menacing outsiders – a tactic he used in the peak of the migrant crisis to popular effect – is the group's founder, Hungarian-born billionaire George Soros.

"The following year will be about the squeezing out of Soros and the powers that symbolise him," Orban said in no uncertain terms in December. Szilard Nemeth, vice-president of the ruling Fidesz party, went further, calling for Soros-backed NGOs to be "swept out" of Hungary.

Continuing its "enemies everywhere" style of rule for the run-up to the 2018 parliamentary elections, Fidesz this month unleashed a billboard and television advertising campaign attacking Soros as a risk to national security.

It was criticised by local Jewish groups and Israel's ambassador to Budapest as having anti-Semitic overtones – a charge Orbán's supporters say is ridiculous given his recent meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu when he publicly pledged his support to the Hungarian Jewish community.

Soros, 86, grew up under Nazi occupation and later communism as a Jew, before he left Hungary and eventually settled in the US. A financier with deep pockets, Open Society says he has since donated more than $12bn to help protect his country and others from authoritarianism.

But Orbán tells his country's people and its increasingly-regulated media a different story.

Soros, the Hungarian leader says, is a shadowy financier, an enemy of the country; he pulls the strings of Hungary's liberal NGOs as they try to prevent a democratically-elected government from pursuing the will of the people.

This includes, Orbán says, his policies against immigration – strongly criticised by the EU and United Nations, but popular domestically – and laws further regulating the media and judiciary.

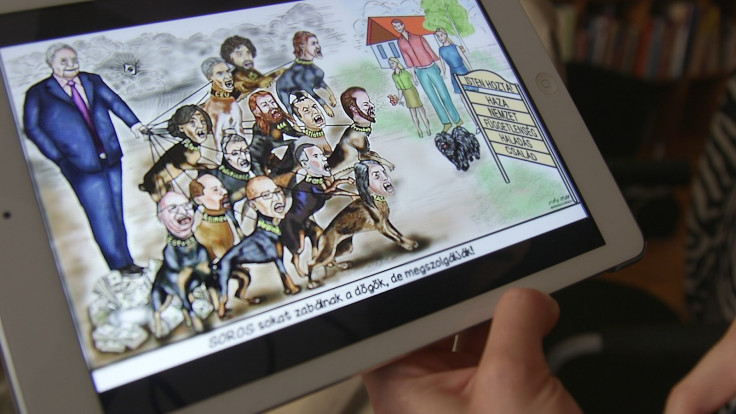

It's a caricature epitomised by a not-so-subtle cartoon recently printed in one of the country's right-wing publications which went viral online among radical right-wing groups.

A sneering Soros is shown holding the leashes to a pack of vicious dogs as they bark at a wholesome-looking Hungarian family. Each frothing animal has the face of an NGO leader said to be an enemy of the country.

One of those dogs is supposed to represent Patent, a Hungarian women's rights group part-funded by Open Society that specialises in helping female victims of violence.

It was only under Orbán in 2013 that domestic violence became a specific criminal offence in Hungary. But a subsequent Human Rights Watch (HRW) report found women were being systematically let down by the authorities and still-patchy legislation.

Watch as Hungarian school pupils learn about sex education, feminism and alternatives to traditional 'male-led' family models. Women's rights and LGBT groups also speak out about a rise in discrimination under the current government.

Victims complained they were ignored by police and social services while being repeatedly abused by their partners. This included, HRW says, while being stabbed and chopped at with knives, axes, and swords; kicked and punched in the abdomen while pregnant; raped; beaten with sticks, prams, iron rods, and thick cables to the point of broken bones and skull fractures; locked in sheds without clothes in winter; thrown off balconies; dumped in remote areas in the middle of the night; and subjected to severe psychological violence.

Far from the all-powerful enemy Orbán's supporters suggest exist among NGOs, Patent's volunteers operate out of a tiny Budapest office tucked away in an apartment block south of the River Danube.

They tell IBTimes UK that life for NGOs in Hungary has become undoubtedly tougher over the years – and that the impact on the women they help could be devastating if it worsens.

"I have a big fear of the main women's NGOs disappearing because they face not only government bullying, but also a disappearing of funding," says Noa Nogradi, a volunteer communications officer for Patent.

"We have less and less resources, and less and less energy – and we're constantly being bullied. It's very hard to keep up our work, and I think our work is very, very important. If we don't do it, then there's nothing.

"There are so many women who always give us feedback that 'if you weren't there then there would have been nowhere I could have turned'.

"I'm quite scared about what will happen to us in that sense."

Patent is just one of dozens of NGOs that could be branded "foreign agents" under Orbán's new Hungary, potentially making it harder for them to raise money and continue their work.

On top of legislative changes, the rise to power of Fidesz has also meant the reestablishment of traditional "Christian" notions of family – and all the misogyny these can involve.

It's a policy that has left the LGBT community also in fear.

Halting LGBT rights

On 8 July, Budapest saw what organisers said was its most popular Pride march in history.

About 22,000 people, dressed in leather and drag, waved rainbow flags while dancing to music down the city's historic promenades and towards the capital's parliament building on the River Danube.

That this year's procession managed to do away with the fences erected on previous marches to protect gay and transgender people being violently attacked by far-right activists – a shocking feature of previous Prides – is a limited success in itself.

But despite the record turnout, activists in the country's LGBT community aren't brimming with optimism for the future.

Csaba Tóth, winner of Mr Bear Hungary 2016, talks about what it was like being gay under Communism in Hungary – and how the current government has left him fearing a return to those dark days.

"I'm sure we cannot be so openly gay in Hungary very soon," says Csaba Tóth.

Tóth, 48, grew up under communism in a small community in the countryside where being gay was taboo. "I had to be hidden ... really hidden," he explains.

His move to the more liberal bars and clubs of Budapest allowed him to finally express his sexuality without fear of attack, and meet others in the LGBT community. He went on to become confident enough to participate in – and win – Mister Bear Hungary 2016.

But the Fidesz government has been swift in trying to cement its Christian vision of what a Hungarian family should be – and been determined to halt the push for gay rights in the EU.

In 2012, it changed the country's constitution to include the definition of marriage as between only a man and a woman, in a bid to permanently block same-sex weddings.

It was the first time a country had made such a move since joining the EU.

The Fidesz government later extended its reforms to include a definition of parent-child relationships that excluded same-sex couples, meaning they and their children would never be legally regarded as a family.

Rounding off a torrid period for the country's gay rights activists, Hungary last year became the only state to block a Europe-wide agreement on LGBT rights.

Tamas Dombos, board member of the Hungarian LGBT Alliance, which acts as the country's main umbrella group for gay and transgender groups, has watched with envy as other EU countries expand LGBT rights.

Speaking to IBTimes UK from his organisation's modest office in Budapest, he tells of how roughly 40% of the LGBT community in Hungary has suffered discrimination of some form in the past 12 months alone.

"There are cases of people not being hired because their employer finds out that they are lesbian, gay or transgender; cases where children were refused from schools because their parents were lesbian or gay; cases where people were forbidden to enter to bars and pubs or to display their intimate relations in those places. Discrimination is quite common."

Public opinion appears to be on Orbán's side, with a Budapest Pride poll last year finding 56% of Hungarians oppose same-sex marriage.

Dombos says politicians have added fuel to the anti-LGBT fire by increasingly using "very nasty" language in public when referring to the gay or transgender community.

This includes special adviser to Orbán, Imre Kerényi, calling for "stopping the faggot lobby"; Mayor of Budapest István Tarlós describing the Pride march as "unnatural and repulsive"; and Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjén decrying homosexuality as "a deviance" and "aberration".

Concerned members of the LGBT community say Orbán could have distanced himself from such language.

Instead, he chose to welcome and speak at an international conference organised by an American-Christian organisation accused of being an anti-LGBT hate group with links to the Kremlin.

The 11th World Congress of Families (WCF) – under the banner of "Making Families Great Again" – met in Budapest in May and saw the Hungarian leader pitch the future of Europe as dependent on restoring "natural" reproduction.

"Our homeland, our common homeland, Europe, is standing to lose in the population contest of the big civilisations," Orbán told the gathering.

The fear among the LGBT community is that the "go forth and multiply" edicts from the government leaves them at best being seen as a non-contributing inconvenience, and at worst a menace to the future of the country.

"All those repressive tools that have been used in Russia might be imported to Hungary as well," Dombos says, fearing the changes already brought in are just the beginning. "Which means that it might be that our activities might be declared illegal ... I'm not saying it will happen it depends on how Europe reacts to it."

Tóth is similarly downbeat.

"I'm a little bit scared, to be honest with you," he says. "I lived in Communism and I don't want to live in this kind of dictatorship again."

LGBT activists say finding allies within the political system for their causes has been difficult. No gay politician in Hungary is even comfortable coming out in public.

They say they have also suffered from an increasingly pro-government press that is unwilling to publicise their concerns.

Transforming the media

It was October last year that Hungary's largest independent newspaper was abruptly shut down.

Népszabadság, a centre-left daily, was the country's biggest selling broadsheet and had printed countless stories critical of the government.

The owners, Mediaworks, bought the paper in 2014 and claimed the decision to shut both print and online operations just two years later was for economic reasons, saying it followed a 74% decline in sales in the last 10 years.

The government – whose senior officials had around the same time been accused of lavish personal travel spending by the paper – welcomed the news, calling it a "rational economic decision".

But the sudden move was described by its own journalists as a "coup" and sparked fears among Orbán's critics that a media clampdown seen under Fidesz had taken its first scalp.

"We are in shock. Of course they will try and paint this as a business decision but it's not the truth," one reporter, who did not wish to be named, said at the time.

Their fears were echoed by other journalists outside the pro-government press, which has largely been shielded from commercial pressures by state-directed public advertising.

Investigative journalist Pal Daniel Renyi wrote on the independent news website 444.hu at the time: "No-one should be in any doubt that Népszabadság is the victim of a political manoeuvre."

The news also went down badly in Brussels.

The European Commission said it was "very concerned" about the development, while Guy Verhofstadt MEP, the former Belgian prime minister and strong critic of Orbán, simply tweeted: "With its current policies, Hungary would not have been allowed to join the EU in 2004."

Despite government claims that Hungary has a more vibrant and diverse press than many other western European states, the country was this year ranked among the lowest for media freedom in the EU by Freedom House.

In 2009 – the year before Orbán came to power – it was ranked among the highest.

Laws passed in 2010 tightened government control of the broadcast sector and extended regulation to print and online media, creating what Freedom House said were "new avenues for political interference".

In the background, the country has also seen a new generation of government-friendly media barons emerge, taking advantage of lucrative state advertising contracts.

"You get government patronage, you then reinvest some of that in creating friendly media outlets," one unnamed owner told the Financial Times of the supposed new rules of media ownership in Hungary.

Critics say it is now common for the government's position on key policies to be parroted by the country's most popular outlets.

After most mainstream TV and radio stations helped Fidesz to be re-elected to power in its 2014 landslide victory, they also proved crucial in helping the government explain its controversial policy during the migrant crisis.

More than 90% of the prime time news items broadcast over the country's most watched TV channel – state-owned M1 – promoted the government position and ran anti-migrant material, a study by Hungarian watchdog Mertek Media Monitor found.

A leaked memo also later revealed public television workers had been instructed by a public agency to avoid showing images of women and children migrants as the government prepared a referendum on the issue.

Hungarian journalist Tamás Bodoky, editor-in-chief of investigative news site atlatszo.hu, speaks about the 'biased' reporting on the 2015 migrant crisis by his country's increasingly pro-government press.

Tamás Bodoky has watched the media landscape in Hungary shift significantly while editor-in-chief of investigative news site atlatszo.hu.

His organisation of six journalists relies almost entirely on donations, including from the Open Society.

Speaking to IBTimes UK, he says the post-Soviet days of when journalists were regarded as "heroes" and essential to Hungary's transition to democracy have slipped away – along with independent media.

"In the 1990s but especially the 2000 years, political and economic powers started to grab media power again," he says.

"Over the seven years since 2010, this process [has been] going further. Now in 2017 we are in a situation where we have a huge pro-government press in Hungary ... The mainstream channels are mostly controlled by the government now."

Added to that has been smear campaigns against journalists critical of the government, he says.

"We are a low budget project but still we are targeted by government smear campaigns. So if you read the pro-government press you will see that we are 'traitors' or 'foreign agents' because, while we are more than 50% crowdfunded, the other comes from international donors."

He continues: "I wouldn't call [Hungary] a dictatorship yet because there's no physical harm to journalists [and] there are no journalists in jail, so we can't compare the situation to Turkey or Russia. But the tendencies are very disturbing ... I'm afraid if it does not stop in a relatively short time, so if this government gets another four years in 2018, that it can lead us exactly to where Turkey or Russia are at the moment."

Orbán's opponents say shrinking media diversity has also been joined by an attempted power-grab on another key tenet of liberal democracy – academic freedom.

Attacks on education

One of the most high-profile institutions caught in the middle of the vicious tête-à-tête between Orbán and Soros has been the Central European University (CEU) in Budapest.

Now ranked one of the top academic centres in the region, Soros founded CEU after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1991 as a champion for open democracy.

It has since stood as a bulwark of liberal thinking in central and eastern Europe.

But its worldview of openness and perceived pro-migrant leanings have come to represent the antithesis to the new Hungary Orbán wants to create.

And this year the government delivered what CEU officials said was a hammer blow to its future in Hungary, describing it as the most serious attack on academic freedom in the EU since the Second World War.

In April, a raft of amendments to the country's Higher Education Law placed new obligations on the 28 foreign-registered universities in Hungary.

This included forcing them to open campuses in their home countries – something the New York-accredited CEU does not have – and demanding they offer Hungarian degrees only.

The government insists its new laws are about levelling the playing field, accusing the CEU of asking for unfair advantages over domestic universities because its degrees are recognised in both Hungary and the US.

Denying they want to close down CEU, ministers also say the measures will prevent some of the foreign-registered universities from issuing dubious diplomas.

But given the short deadline to comply, the CEU says the new laws make its continued operation in Hungary "impossible" and would force them to shut its doors.

"If they succeed in forcing us out of Budapest this would be the first time in Europe that a member of the EU had tried to shut down a university – and that's why it's awaken outrage across Europe and a tremendous amount of opposition in Hungary," says CEU President Michael Ignatieff, a former head of the Liberal Party in his native Canada.

The measures have also been condemned by leading academics worldwide, along with the EU and US government who warned the law change "threatens academic freedom and independence".

Despite supposedly benefiting from the level playing field the government says it wants to create, Hungarian universities have also condemned the move.

It's a row where Soros has once again become a convenient enemy for the government.

University staff repeatedly dismiss government officials' branding of CEU as "Soros university", saying the billionaire assists the university with a no-strings-attached endowment and has no involvement in the day-to-day running of the institution.

"I don't take orders from Mr Soros. I admire him, I respect him – I'm frankly disgusted by the attacks upon him – but he's not my boss," Ignatieff insists.

Despite tens of thousands marching through the streets of Budapest in opposition to the new laws, the government has continued on regardless.

It's a resilience Ignatieff says he has come to expect – but one he warns could set a dangerous precedent for the continent.

"[If CEU closed] where would that leave the European Union? It leaves it, in my view, not just in tatters morally but in tatters legally, because these treaties either mean something or they don't.

"The world is full of people who don't like the freedom of universities ... If the Hungarian prime minister succeeds in driving us out it would give incentive to every other authoritarian leader not only in the region but around the world [to do the same]."

The European Commission has already found the higher education law amendments to be unlawful, violating the right to academic freedom and freedoms to provide services. It started legal proceedings against the Hungarian government in April.

Should the law go unrepealed, however, CEU may be forced to stop enrolling new students as of January 2018.

Rewriting history

While changes to higher education has seen Fidesz accused of trying to sweep out troublesome universities, reforms to the country's schools have also provoked a backlash and thousands to protest.

Schools were taken from the control of local authorities in 2013 and a central body now regulates the system. It has increased teachers' workload and forced teachers to use two government-approved books per subject, per year.

In what is one of the more extraordinary charges against Orbán and Fidesz, ministers are also accused of changing school history lessons to paint themselves in a positive light.

László Miklósi, chairman of Hungary's Independent Association of History Teachers, speaks out about a new set of state-approved school history textbooks which allegedly paint a biased picture of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

László Miklósi, chairman of Hungary's Independent Association of History Teachers, says one state-approved textbook has shown dangerous bias.

Intended for 14-year-old pupils, "History Eight" focuses on Hungary's post-Second World War period.

The book's publisher, Jozsef Kaposi, said Orbán's inclusion was necessary after the government changed the curriculum in 2012 to include a 1945-present course.

But Miklósi says it paints a flattering picture of Orbán not seen before, and gives insulting descriptions of his opponents while welcoming the Fidesz leader as a "foundational figure for modern Hungary".

Furthermore, the book requires students to read their Prime Minister's speech on the migrant crisis, where he explains why former colonial powers accept high levels of immigration due to their "imperialist mindset", compared to Hungary which "will never become such a country".

Miklósi finds the inclusion at odds with the principle of keeping politics out of schools, adding: "At the end, the children must complete a task in which they have to prove, using the content, and not the words, why prime minister Viktor Orbán is right."

Agnes Kunhalmi, Hungary's parliamentary cultural committee chairwoman, and a Socialist Party MP, said amid the row over the new textbooks: "We are at the point in this autocracy where Orbán is featured in a schoolbook along with his opinion on migrants.

"What kind of government writes its own political hate campaign into a history schoolbook?"

It's the kind of government, Orbán proudly admits, that is trying to rewrite how Hungary and Europe thinks about itself.

In his State of Nation address in February, he rallied against "the globalists, the liberals ... and the swarm of media locusts" who had ridden roughshod over popular will, including issues like immigration.

Hungary is surrounded by "large predators swimming in the water," he went on to warn, backed by "the transnational empire of George Soros, with its international heavy artillery and huge sums of money".

Fidesz's mission, Orbán said, must be to win next year's parliamentary elections so it has another four years to face down these "enemies" and continue the illiberal project.

With the left and liberal political opposition parties still weak after decades of scandal-ridden misgovernance while in power, victory for Orbán is likely.

Whether his illiberal revolution can spread to other EU member states, however, depends in part on how Brussels reacts.

Orbán is a master of salami tactics, his opponents warn – cutting away liberal democracy piece-by-piece until there's nothing left but authoritarian rule.

It's a strategy that some complain the EU has failed to tackle.

They urge Brussels to punish the Hungarian government for straying from the liberal pack, and ignoring EU laws and values.

Given the country's economy is heavily bolstered by the billions of Euros it receives from the EU every year, the bloc's bargaining power could be substantial to this end.

It's a move that Orbán's supporters would, however, say proves that the real enemy of democracy on the continent is Brussels, with an "our way or no way" standpoint.

Publicly, the European Commission has been making big of the need for dialogue with Hungary, while also piling the pressure through legal challenges which could lead to heavy fines.

But should the Commission's policy fail, it would likely leave Orbán and his supporters emboldened.

Some fear the worst for where that leaves Hungary.

For the investigative journalist Tamás Bodoky, it'll be a country that gives him and his team no shortage of scandals and corruption to uncover.

But the biggest story of them all - how Hungary is changing under Orbán - could be the most alarming, he says.

"An autocratic state with central powers, no checks and balances and with a central propaganda media and suppressed free press – I think this is a very clear example of the making of an authoritarian state," Bodoky warns.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.