Mooncake Mid-Autumn Festival 2014: The History Behind This 3,500-Year-Old Tradition

The Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as the Mooncake Festival or Lantern Festival, is one of the most important festivals of the year for the Chinese peoples around the world, and dates back over 3,500 years.

Held on the 15<sup>th day of the eighth month of the Chinese calendar, the festival is held to celebrate the harvest as well as to worship the moon, and the customs are also observed by Vietnamese people (who were colonised by the Chinese in 111 BC).

People celebrate by giving mooncakes filled with lotus paste and a salted egg yolk to their friends and neighbours, while children attend lantern parades holding colourful lanterns, either made from paper or more recently, electronics, and families attend big lantern parades and exhibitions.

Some Western media over the years have tried to elude that mooncakes are primarily given out today as bribes for corrupt government officials, but this is a clear misunderstanding of the rich traditions and cultural symbolism behind the festival.

Join us as we take a look at the origins of the festival and the reasons why mooncakes are so synonymous with the celebration.

What are mooncakes and why do Chinese people eat them?

Many traditional customs practiced by Chinese people today all over the world are based on events and rituals that have been passed down through thousands of years of Chinese culture, and many originate around remembered events of great crisis or strife.

Similarly, the tradition of giving mooncakes to friends, relatives and colleagues during the Mid-Autumn Festival is a reminder of the rebellion which succeeded in overthrowing the Mongol dynasty, which ruled China from 1271-1368 AD.

The Mongols had attempted to invade China many times in ancient times and eventually succeeded under the leadership of Kublai Khan during the 13<sup>th century.

Khan set up the Yuan dynasty and created a new social order which favoured Mongols, West and Central Asians, with Chinese subjects (particularly those from the fallen Song dynasty) in the bottom tier.

During the century that the Mongols were in power, their rule was oppressive, forbidding Chinese subjects to gather in public or own weapons, as well as levying heavy taxes, while making bad land management decisions that led to poor crops yield.

Mongol guards were posted outside the homes of all Chinese subjects.

One knife was given to ten Chinese families to use during meal times to cook, after which the implement was taken away again.

The families also had to support their Mongolian guards by giving them food and wine, and even their daughters. Chinese people were not even allowed to handle bamboo, in case they used it to manufacture bows and arrows.

The story goes that Liu Bowen, the confidant of the rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang, suggested that the rebellion be timed to coincide with the Mid-Autumn festival.

Zhu applied for and got permission to distribute thousands of mooncakes to Chinese residents in the Mongol capital as a blessing to the longevity of the Mongol emperor. Inside each cake was a piece of paper saying, "Kill the Mongols on the 15th day of the eighth month".

The plan succeeded, since Mongols did not eat mooncakes, and they were overthrown, retreating back into Mongolia, while Zhu founded the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD).

Although some Chinese historians are sceptical that the cakes were used in this way, mooncakes have historically been made with specific moulds and always include three to six Chinese characters imprinted into the top.

Today, the Chinese characters usually refer to what flavour the cakes are, as it has become trendy to make mooncakes with a wide variety of fillings, including traditional ones like sweet bean paste, jujube paste and five kernel (a filling made from five types of seeds and nuts mixed with maltose syrup), as well as unusual flavours like chocolate, yam, orange and pandan leaf.

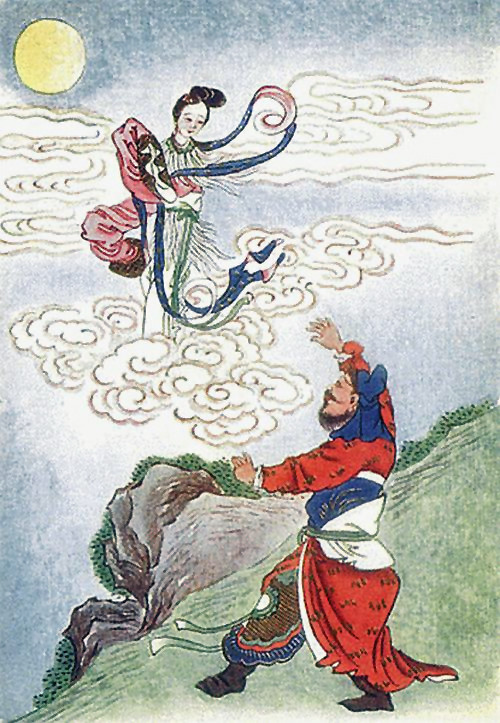

The Legend of Chang'e and Houyi

Going back even futher before the Yuan dynasty is the Romeo and Juliet-esque legend of Chang'e, the moon goddess, and her consort Houyi, which dates back to literature from the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BC).

There are three popular versions of the tale of Chang'e and Houyi. The most popular version states that Chang'e and the archer Houyi were once immortals, a married couple living in heaven.

One day, the ten sons of the Jade Emperor in heaven transformed into ten suns, which caused the Earth to scorch and all the plants to die.

The Jade Emperor summoned Houyi to stop his sons from ruining the Earth, so Houyi shot down nine of the Jade Emperor's sons, leaving just one to be the sun.

To punish Houyi for killing nine of his sons, the Jade Emperor banished Houyi and Chang'e to live as mortals forever on Earth.

Chang'e was incredibly upset at losing her immortality so Houyi went on a long quest to find the Pill of Immortality/Elixir of Immortality.

In one version of the story, Chang'e consumes the pill/elixir to prevent Houyi's evil apprentice Feng Meng from getting hold of it, while in another version, she finds the pill out of curiosity and consumes it by accident.

In all versions of the legend, Chang'e becomes immortal and flies to the moon, where she has only the company of a jade rabbit.

She and Houyi are separated forever, although some retellings claim that during the Mid-Autumn festival, Houyi can cross the milky way and get closer to Chang'e as the distance between them is lessened by the new moon.

The tradition of holding lanterns is thought to be people on Earth holding and waving the lanterns near where Houyi is crossing the milky way, so that Chang'e knows where to look for him.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.