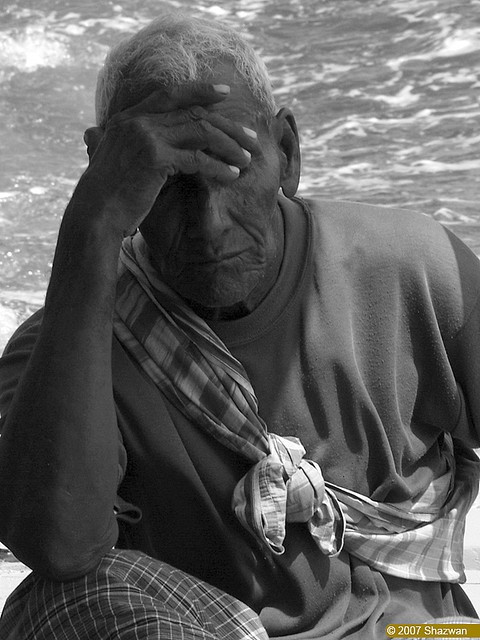

More than a men's issue, paternal depression affects us all

No one is entirely sure whether paternal depression is on the rise. That's because, until recently, no one had thought to ask new dads about their mental health.

The potentially horrific extremes of postnatal depression for mothers are well known, of course, but the medical profession and wider society tended to assume that a new dad would quickly wet the baby's head with his mates down the pub then be merrily back to work and life as normal the next day.

Research published last week by the National Childbirth Trust is the latest to kick such lazy assumptions into touch. While paternal depression should not be confused or conflated with maternal postnatal depression or PND (which almost certainly has unique physiological and endocrine elements) the new findings detail the extent to which the social, physical and emotional stresses of a new baby can impact upon men's mental health.

"It is incumbent on men to take responsibility for their own mental and emotional health, and to understand that a refusal to do so not only puts their own health, happiness and wellbeing at risk, but also that of their families."

More than a third (38%) of new fathers report feeling concerns about their mental health. Other studies have found one in 10 fathers has reactive depression, with peak risk around three to six months after the baby is born. One study in southeast England found that one in 30 fathers had developed at least one major symptom of clinical depression.

That same study found a baby raised in a family with a depressed father was nine times more likely to require medical intervention for speech and language development and seven times more likely to develop behavioural and social relationship problems. If nationally representative, this would be equivalent to around 25,000 children affected every year in the UK, and make no mistake, these children are indeed affected.

A wealth of other research has identified significant associations between paternal depression and negative consequences for children's health, emotional well-being and development.

Why does this happen? Well, most obviously a depressed father will engage less well and less often, meaning babies develop fewer strong, healthy attachments. Just as importantly, however, his wife or partner will be affected by the illness and the stress placed upon her will in turn be passed on to the child.

As research collated by the Fatherhood Institute details here, parents' abilities to cope with the demands of a new baby hinges on the quality of the relationship between them. The quality of mothering provided to an infant has been linked with the support the mother receives from her partner. Women who enjoy the full support of their partners are more closely bonded to their children, and more responsive and sensitive to their needs.

Greater paternal involvement in infant care and other household tasks is correlated with lower parenting stress and depression in mothers. Reducing mothers' sole responsibility for infants and young children through more active paternal care, and supporting mothers to interact with adults outside the child-rearing arena (for example, in employment) are likely to contribute to better mental health among mothers and reduced parenting stress. All of this is severely compromised when a father is struck by depressive illness.

No man is an island

In return, it should come as no surprise that the single biggest risk factor for new fathers developing mental health problems is their female partners having mental health problems. No man is an island, nor any woman or child. It makes little sense to consider the mental health of new mothers in isolation from their male partners or vice versa, and of course the exact same dynamics apply where same-sex couples are raising a baby.

"The study found a baby raised in a family with a depressed father was nine times more likely to require medical intervention for speech and language development and seven times more likely to develop behavioural and social relationship problems."

It is more than a decade since academic researchers began to fully quantify the extent and implications of paternal depression, and as far back as 2008 psychiatrists were recommending that routine heath checks on new mums and babies should include screening the father's mental health, as is always performed for mothers. This remains little more than an aspiration. While the Royal College of Midwives is now moving towards what they call a "whole family approach to care" there is still no systematic approach to ensuring paternal depression is picked up and addressed.

Perhaps the most encouraging aspect to the NCT report, however, has been the sympathetic reporting of the issue. When similar research was published three years ago, one GP wrote scornfully in a British newspaper: "Women have a difficult enough time as it is, trying to get some understanding of what they are going through in the early months of a child's life, without men trying to muscle in on the act and get more attention for themselves."

This remains one of the most staggeringly stupid sentences I have ever had the misfortune to read. As with all issues of men's mental health, the single biggest obstacle for new fathers in accessing support and medical intervention is our own stubbornness and misplaced pride, our refusal to make a fuss or admit to a problem. There are many effective treatments available for depression and other mental illnesses, and they do not include "manning up" and "pulling yourself together". This is something most men know in their heads, but too often struggle to believe in their hearts.

It is incumbent on men to take responsibility for their own mental and emotional health, and to understand that a refusal to do so not only puts their own health, happiness and wellbeing at risk, but also that of their families. However there is a parallel responsibility on the primary health care system to reach out to men, to meet them at least halfway to the place they are. This is never more vital than when cradling a new, dependent life.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.