Mysterious nodules on 800-year-old skeleton from Troy contain intact DNA of deadly bacteria

The unprecedented discovery reveals details of the history of maternal health in the Byzantine era.

The death of a 30-year-old pregnant Byzantine farmer in the 13th Century on the outskirts of the ruins of Troy has been traced to sepsis, with the DNA of the bacteria that killed her preserved remarkably intact.

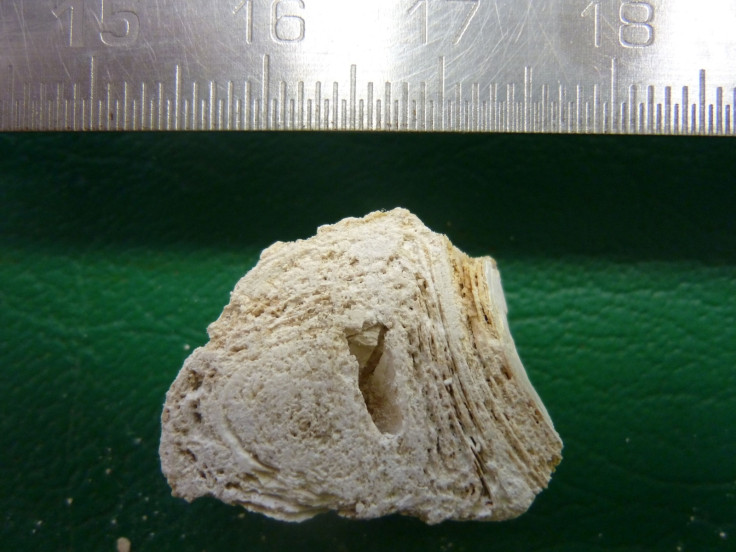

Archaeologists excavating the burial site in Anatolia in present-day Turkey found suspicious-looking nodules at the base of the woman's chest, just below her ribs.

Carbon dating showed that the nodules were between 790 and 860-years-old. From the structure of her skull, the woman was estimated to be 30-years-old at the time of her death.

After ruling out tuberculosis as the cause of the nodules, pathologist Caitlin Pepperell of the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the US cracked them open to find that they contained 'ghost cells' of the bacterium that killed the woman.

These ghost cells, or microfossils, were of Staphylococcus saprophyticus, which usually causes urinary infections, and Gardnerella vaginalis, which can cause pregnancy-related infections. There was also male human DNA preserved within the nodules, suggesting that the woman had been pregnant with a baby boy at the time of the infection.

The DNA was amazingly well-preserved, with DNA from the micro-organisms that killed the woman still intact after close to 1,000 years.

"Calcification made little tiny suitcases of DNA and transported it across an 800-year timespan," said Pepperell in a statement. "In this case, the amount and integrity of the ancient DNA was extraordinary."

Typically only about 1% of the ancient DNA would survive this length of time, she said. But the Staph in these nodules still had between 31 and 58% of their DNA intact.

"There was something really interesting about the way this material was preserved," she said. "The quality of the genetic data is unparalleled."

The mineralisation of the nodules – and hence the preservation of the DNA – is rare, but related to the fact that the woman was pregnant.

"The placenta is very prone to calcification as there is a lot of movement of calcium to the foetus. The biomineralisation process can occur very quickly," Pepperell said.

A gruesome death

Anatolia was a tough place to live in the 13th century. The skeleton had the hard manual labour of agricultural work etched into its bones: the stresses and strains of the daily routine led to early degeneration of the spine and joints.

"People were struggling with physical strains and infectious diseases and only a few lived beyond the age of 50. Many newborns did not survive infancy and almost all skeletons of children show signs of malnutrition and infection," says study author Henrike Kiesewetter, an archaeologist at Tüebingen University in Germany.

It was an especially bad time to be a woman. The bacteria in the nodules are thought to have caused chorioamnionitis, or maternal sepsis. The Staph infected the woman's placenta, amniotic fluid and the membranes surrounding the foetus.

Many women died in childbirth or from complications during pregnancy at this time. But the discovery of a pregnancy-related death in the fossil record is unique, according to study author Hendrik Poinar of McMaster University in Canada.

"There are no records for this anywhere," he says. "We have almost no evidence from the archaeological record of what maternal health and death was like until now."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.