Norse Mythology and Volcanoes: Vikings, Fire Gods and Screaming Zombie Dwarfs

When Vikings first arrived in Iceland in the ninth century, they were faced with an entirely new phenomenon – volcanic eruptions.

Having come from countries across Scandinavia, where there is no volcanic activity, how they would have reacted to fire and molten rock exploding from the ground has become a subject of debate.

As volcanic activity continues at the Bardarbunga and Holuhraun area in Iceland, scientists are able to provide accurate details about the size of earthquakes and lava flow it is producing. Yet despite knowing this information, being in its vicinity would probably still unnerve most people, at least to some degree.

Not the Vikings, however. Or so historical texts would have you believe.

There is only one mention of volcanoes in ancient Norse sagas, which indicate that Icelandic Vikings had a relaxed and non-religious relationship with volcanoes.

But can this really be the case? Mathias Nordvig, from Denmark's Aarhus University, thinks not. Instead, he believes Vikings' feelings about volcanoes are hidden within mythology and stories passed down through generations.

Nordvig initially began researching the relationship between Vikings and volcanoes after a colleague, who was researching human vulnerability to disasters, had asked about early Icelandic reactions to volcanoes.

He said because there is very little writing about it, some people believe this is an indication that Vikings were not interested in volcanoes, or that they just thought they were common storms:

"[However] if we dig into the early literature we can find several instances where the volcanoes in Iceland are very important to the self-conception and the way they perceive the world in general."

Volcanic mythology around the globe

"If we compare with other societies all over the world who live close to volcanoes - just look at Hawaii or New Zealand or Indonesia - you see people have rich mythology, many legends, many stories," Nordvig said, arguing that as other cultures living close to volcanoes have such strong and enduring myths about them, it would be unusual for Vikings not to have generated some of their own.

Most famously, Hawaii mythology tells of Pele, goddess of the volcanoes. Although there are many stories about Pele, one popular story is that she was exiled to the islands by her father because of her temper, and when she was angry, eruptions would occur.

Nordvig explained that in Indonesia, even after the country converted to Islam, stories about volcanoes are still told using Hindu terminology – suggesting that even when society changes, these stories are so embedded in culture that they do not.

Why then, would the Vikings have been immune to the allure and reverence other cultures have for volcanoes? Nordvig says they weren't, but their stories are masked through mythical metaphors.

Icelandic Vikings and volcanoes

He said there is one poem in particular that is used to describe Ragnarok, or the Viking apocalypse, which has "clear indications" that they are talking about a volcanic eruption. In 934, shortly after the Vikings arrived, there was a huge volcanic eruption in Iceland – the Eldgjá eruption, meaning chasm of fire. Lava poured from the volcano and it continued for years, with the effects felt as far away as China.

The only historical account from Viking history was that a man had been living in the area but had to move – not the dramatic account you might expect from a group of people who previously had no concept of volcanoes.

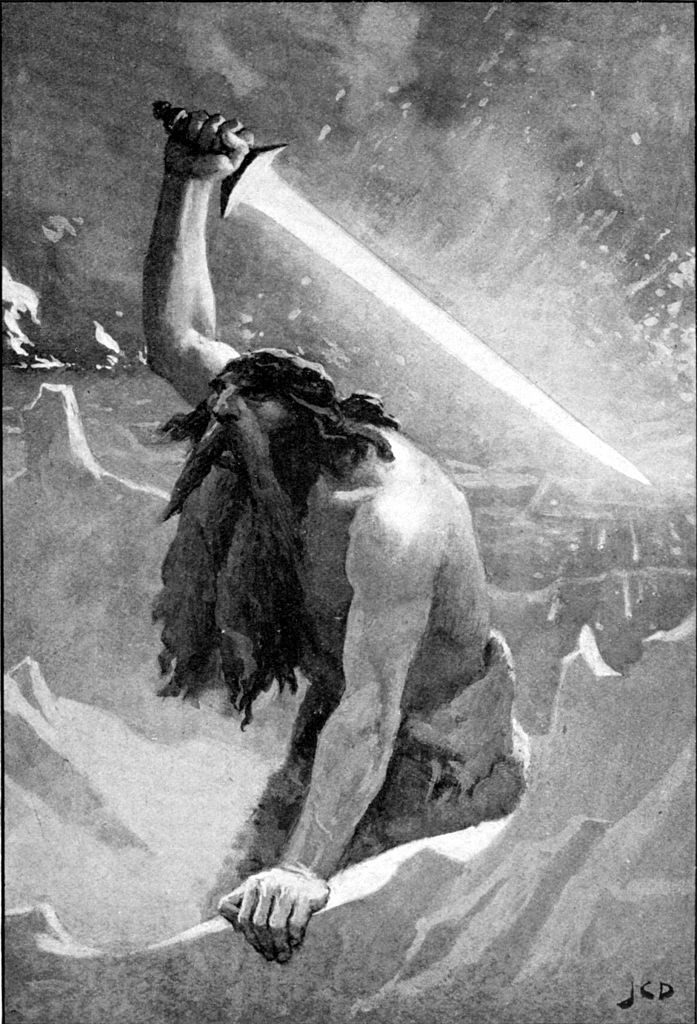

In the poem, however, a giant has woken up and loosens his bonds: "This refers to the idea that the Norse god Loki was tied up underneath the earth and created earthquakes. There was a poisonous snake that dripped venom in his face and whenever he shudders from the pain, he would create earthquakes.

"This actually relates to the experience you have in the beginning of an eruption - there are earthquakes swarms at the beginning of the event – before we see any lava before anything else happens we have earthquakes, and lots of them."

Following this, the fire people of Surtr are said to be following the road to hell, suggesting there is fire moving underground. Surtr – the fire giant – is "very much connected to the volcanic phenomenon", Nordvig said.

Dwarfs, fire giants and the eruption

"The important thing about dwarfs is that they are not these funny bumbling creatures that we think of today. Presumably, in the old Norse context before Christianity, dwarfs were more or less demonic creatures living in the ground. Quite often they're described as corpses, or looking like corpses", said Nordvig.

"What happens is that they stand before the stone doors howling. We know from mythology that the dwarfs are described as living in the ground as maggots live in flesh. So when they stand before the stone doors, they have come out and are making these loud noises. If you've been near a volcanic eruption, you known the sounds are loud, they're very loud hissing sounds that pulsate and roar."

Nordvig explained that the image of the fire giant Surtr emerging from the ground and the dwarfs howling both mirror events that take place before an eruption. The poem then says that men trek the road to hell and that the sky splits apart.

"This is when we have this massive eruption, when the lava bursts out of the ground. If we compare with the notion from this eruption, if these flames or fire fountains they reached more than 1km into the sky, we may have a comparable image with this description."

Nordic mythology

Scandinavia is known for its folklore, with trolls and dwarfs featuring throughout Norse mythology. After first arriving in Iceland, the Vikings had very little in the way of writing and instead, there was an oral culture. This, Nordvig said, means we should expect their stories to be told in poem and song, as with other cultures from the time.

"These Norwegians and other Scandinavians came to Iceland from an area that has no volcanic activity to a place that has a lot and they have to use whatever frame of reference they can to express the sentiments. Naturally they will try to make analogies, for instance giant beings that live in the ground and are made of fire and rock and stone.

"We know a lot of stories about rock trolls from Iceland and the rest of Scandinavia - they use these images to tell these stories. And they are slowly compressed in these easy to remember poems that they tell and retell over and over.

"You might assume that one of the reasons for doing that is to know how to react in these situations when you see the warning signs."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.