Patagonia's glaciers are melting at an alarming rate due to global warming

Near the tip of South America lies an unbroken mass of ice about 350km long, covering an area of 12,363sq km. The Southern Patagonian Ice Field is the third largest reserve of fresh water on Earth (after the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets.) However, the ice is melting at an alarming rate as the planet warms up. The giant ice cap has retreated by 1km since the early 1990s, and 10km since the late 19th century.

Almost all of the 47 large glaciers in Patagonia's Los Glacieres National Park have retreated over the past 50 years due to warming temperatures, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). Studies show that glaciers in Patagonia are receding at a faster rate than anywhere else on Earth.

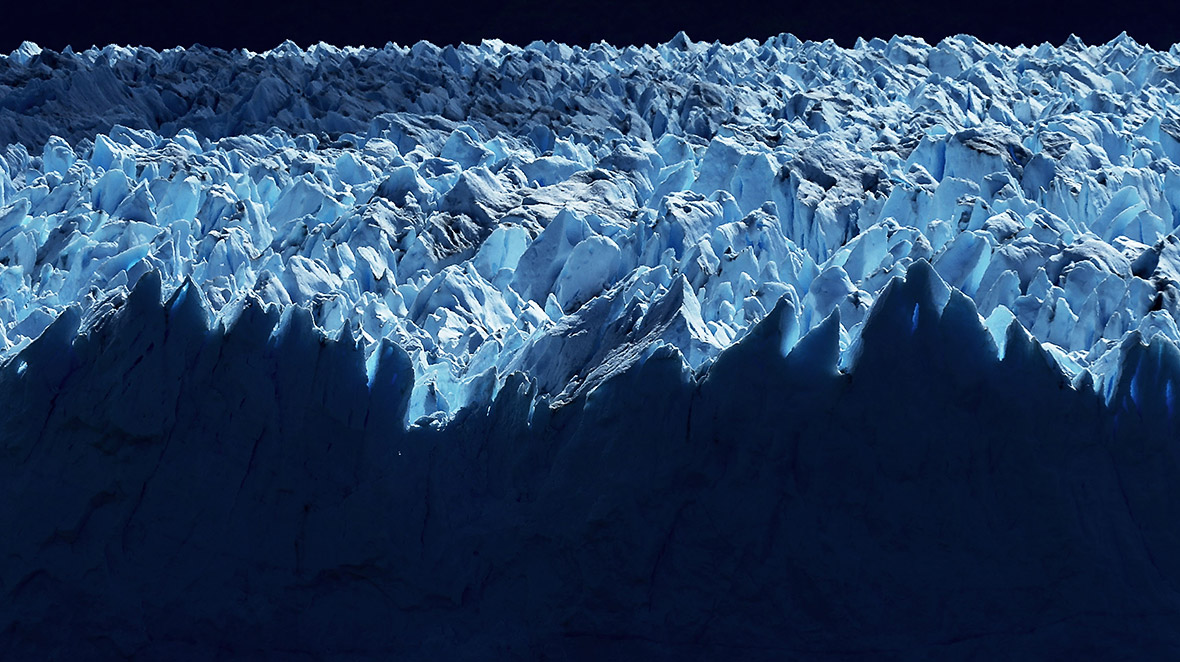

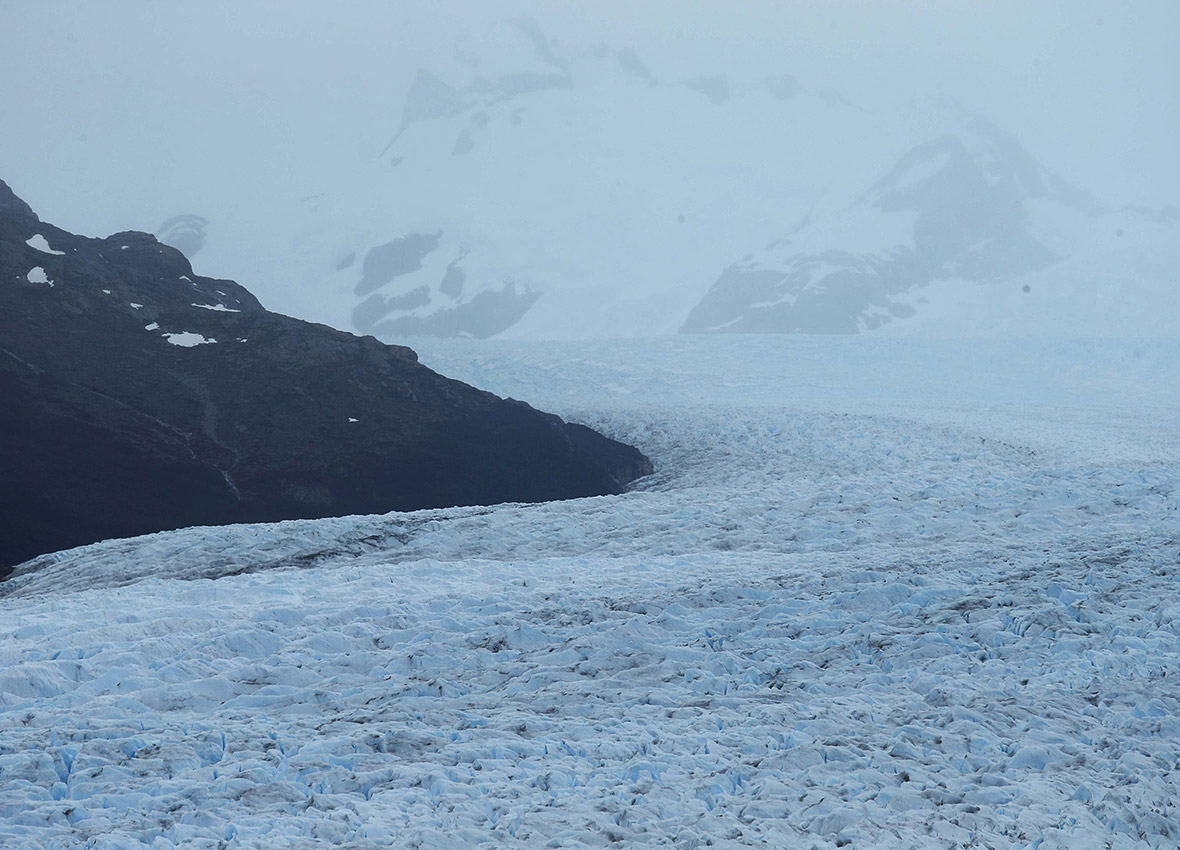

These pictures by Getty Images photographer Mario Tama capture the incredible scale of these glaciers. They also reveal the surprising beauty of this frozen landscape, with its jagged ice fields, towering cliffs, bright blue icebergs and turquoise pools.

The nations of the world are attending the COP21 UN climate change conference in Paris, which runs from 30 November to 11 December. It is hoped that by the end of the summit, the world will have come to an agreement to limit emissions in order to prevent global warming exceeding 2C above pre-industrial levels.

The last time that the nations of the world struck a binding agreement to fight global warming was 1997, in Kyoto, Japan. Things have changed dramatically over the past 18 years. The differences can be measured in degrees on a thermometer, trillions of tons of melting ice, a rise in sea level of a couple of inches.

Global warming since 1997: the cold facts

The average glacier has lost about 39ft, or 12m, of ice thickness since 1997, according to Samuel Nussbaumer at the World Glacier Monitoring Service.

The West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets have lost 5.5 trillion tons of ice, according to Andrew Shepherd at the University of Leeds, who used Nasa and ESA data.

At its low point during the summer, Arctic sea ice is on average 2,123,790 sq km smaller than it was 18 years ago, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Centre.

The seas have risen nearly 2 .5in, or 6.2cm, on average since 1997, according to calculations by the University of Colorado.

The five-year average surface global temperature for January to October has risen by nearly two-thirds of a degree Fahrenheit, or 0.36 degrees Celsius, between 1993-97 and 2011-15, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In 1997, Earth set a record for the hottest year, but it didn't last. Records were set in 1998, 2005, 2010 and 2014, and it is sure to happen again in 2015 when the results are in from the year, according to NOAA.

With 1.2 billion more people in the world, carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels climbed nearly 50% between 1997 and 2013, according to the US Department of Energy. The world is spewing more than 100 million tons of carbon dioxide a day now.

The five deadliest heatwaves of the past century have come in the past 18 years: Europe in 2003, Russia in 2010, India and Pakistan in 2015, Western Europe in 2006 and southern Asia in 1998, according to the International Disaster Database run by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disaster in Belgium.

The number of weather and climate disasters worldwide has increased 42%, though deaths are down 58%. From 1993 to 1997, the world averaged 221 weather disasters that killed 3,248 people a year. From 2010 to 2014, the yearly average of weather disasters was up to 313, while deaths dropped to 1,364. Eighteen years ago, the discussion was far more about average temperatures, not the freakish extremes. Now, scientists and others realise it is in the more frequent extremes that people are truly experiencing climate change.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.