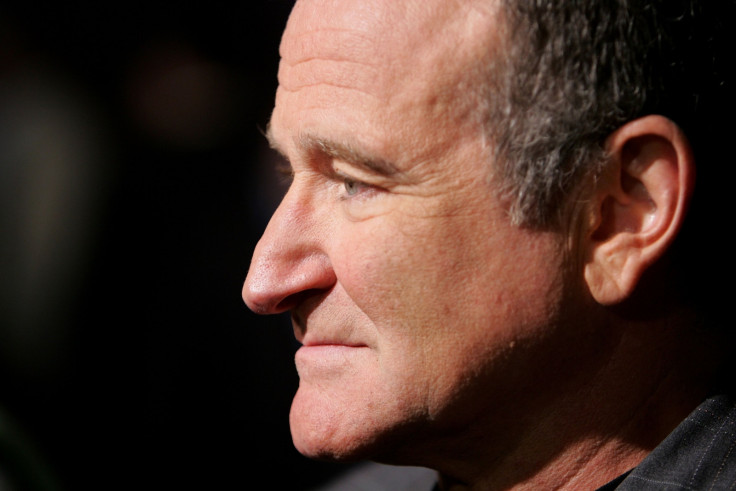

Robin Williams death 1st anniversary: Male suicide and mental illness is a 'silent epidemic'

To say Robin Williams's death came as a shock is an understatement. Those of us with ordinary lives found it difficult to fathom that someone as iconic, effervescent and electric as the comedian and actor could want to end their own life. But as the news sunk in, Williams's death left behind another legacy – it sparked a long-overdue public debate about men, mental health and suicide.

Suicide is a predominantly male problem. It is the biggest killer of men aged between 20 and 49 and of the 5,981 suicides that occurred in Britain in 2012, 4,590 were men. In February, the proportion of men taking their own lives in the UK reached its highest level for more than a decade – with 19 deaths by suicide for every 100,000 men in 2013.

Yet despite these figures, male suicide has been described as a "silent epidemic" because of its substantial contribution to male mortality and due to the reluctance of men to seek help for mental health problems. Women are more likely to suffer from depression but men are far less likely to talk about it.

Mind, a leading mental health charity in the UK, has published research that revealed just 23% of men would see a GP if they felt low for more than a fortnight, compared with a third of women. This could be biological, but it could also be because when asked, women are more likely to report symptoms of common mental illness.

One in four women will require treatment for depression at some point in their lives, compared with one in 10 men. And even if men do seek help from a GP, depression may be misdiagnosed as something else because they present different symptoms to a doctor.

Highest risk of suicide

Joe Ferns, executive director of policy, research and development at the charity Samaritans, says middle-aged men were the group at highest risk of suicide in the UK. He said: "In our Men and Suicide report, our research showed that working-class men aged 45 to 54 are at greatest risk of taking their own lives, with alcohol misuse, economic deprivation, including joblessness and debt, as significant contributory factors. The risk of suicide rises by 10 times for this group."

To turn the problem around, he says we need to encourage men to talk. "To change this situation we need to make it easier for men to speak out and reach men who may be less comfortable about opening up and talking about their problems," Ferns said. "Samaritans is there round the clock, every day of the year, to listen and offer confidential support to those struggling to cope."

But why are women more likely than men to seek help for depression or mental illness? A fundamental reason is the enduring and archaic male stereotype and the concept of masculinity, both of which dictate the way men are brought up to behave and the roles and behaviours society expects of them. Many of these unattainable expectations put incredible pressure on men, as do gendered stereotypes and societal expectations of women.

Masculinity is associated with power and control, which simply does not fit in with liberal post-war culture and the changes to the roles of men and women in modern society. It is the social construct of masculinity that seeps into many of the factors that contribute to high male suicide rates in Britain and the United States, where the suicide rate has been around four times higher for men than women.

According to the Samaritans, men are more likely to commit suicide after the breakdown of a relationship and are more likely to use drugs or alcohol "in response to distress".

Many assumed severe depression was the sole cause of Williams's suicide. But as the Samaritans report explains, suicide is an individual act that can rarely be attributed to one cause but is the "tragic culmination of mental health problems, feelings of defeat, entrapment, that one is worthless, unloved and does not matter".

Williams's struggles

The news that Williams was suffering from the early stages of Parkinson's disease made his death easier to accept, as there was a tangible reason why he no longer wanted to live – a degenerative disease that would gradually make his body frail.

But even before this revelation, there were signs of sadness in his life. He had previously struggled with alcoholism and drug use, sought treatment for depression and anxiety and is reported to have had Bipolar disorder. His death was down to a complicated combination of factors, circumstances and emotions.

Williams's death prompted a worldwide outpouring of grief for the actor who brought alive every role he took on, from voicing the Genie in Aladdin and playing a cross-dressing divorcee in Mrs Doubtfire, to the isolated technician in One Hour Photo and the the comedy radio DJ in Good Morning Vietnam.

But the shock of his suicide opened our eyes to a problem that had been overlooked for years and sparked discussion about men, mental health, stigma and suicide. Talking about the problem is a step towards addressing it, if it means men are free from the constraints of stigma to seek help.

"One in four of us will experience a mental health problem each year. For men in particular, it can be an awkward subject to talk about and research shows that where mental health is concerned, the attitudes of men are changing at a slower rate than those of women," said Kate Nightingale, of the anti-stigma campaign Time to Change run by charities Mind and Rethink Mental Illness. "All too often mental health issues are seen as the elephant in the room. But we don't need to be experts to talk about mental health."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.