Secrets hidden in undelivered 17th-century letters to be revealed with X-ray tomography

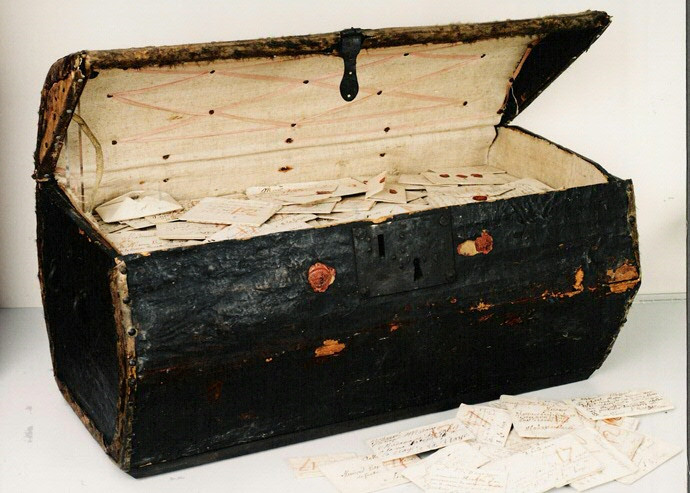

Gossip and scandal of 17<sup>th-century France is set to be revealed through the contents of thousands of undelivered letters found in an old trunk in the Museum for Communication in The Hague. After being granted access to the 2,600 letters, scientists plan to use X-ray tomography (the same technique used to decipher the Dead Sea Scrolls) to uncover the contents of the correspondence.

The letters are the product of a diligent postmaster at The Hague. Simon de Brienne and his wife Maria Germain would hold on to letters when they could not be delivered – be it through the recipient moving, dying or being refused – in the hope someone would come to collect them.

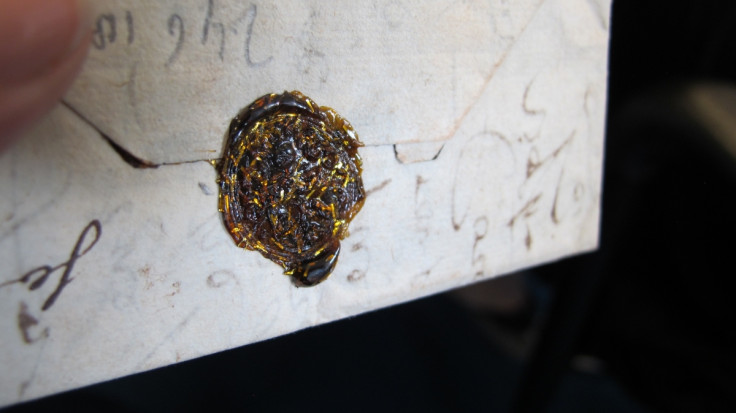

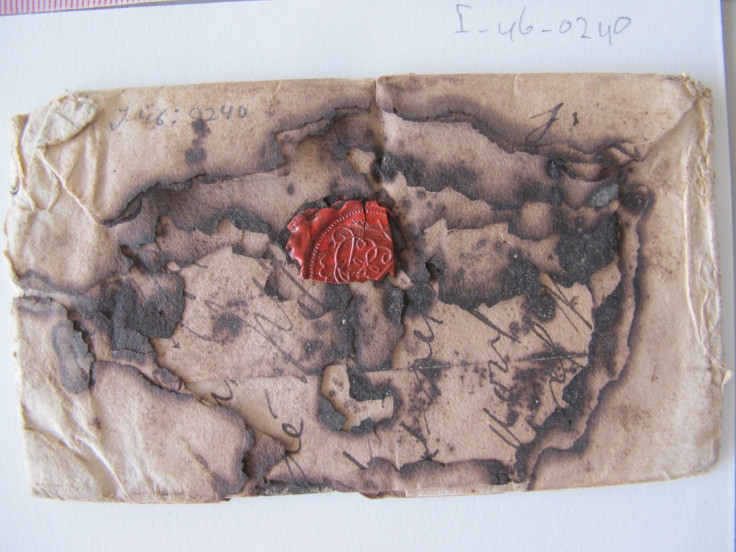

Centuries later, scientists from the universities of Leiden, Groningen, Oxford, Yale and MIT will read the letters to learn about life in early modern Europe. As well as the content of the letters, the team also plans to analyse how the letters were sealed and folded.

Nadine Akkerman, leader of the Signed, Sealed, Undelivered project, said you can learn a great deal about a letter by the way it was folded – similar to a signature. "We call letterlocking: folding and securing letters so no one could secretly read," she said. The team will analyse the letters without opening them. They will use advanced scanning technology to read the letters without breaking the seals – something Akkerman calls a "revolutionary new field of research".

They also say the letters offer an unprecedented opportunity to learn more about life at the time – including families on the run following religious persecution under Louis XIV. David van der Linden, one of the researchers in the project, said the letters show the emotional toll separation had on families at the time.

Another letter in the collection was from a woman writing to a Jewish merchant in The Hague on the behalf of a "friend". She had been a singer with the Hague opera and had left for Paris when she discovered she was pregnant. In the letter, she asks for money to return – but the merchant refused the letter, her fate unknown.

Daniel Starza Smith, a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at Oxford University, said: "Something about these letters frozen in transit makes you feel like you've caught a moment in history off guard," he said. Many of the writers and intended recipients of these letters were people who travelled throughout Europe, such as wandering musicians and religious exiles. The trunk preserves letters from many social classes, and women as well as men.

He added: "Most documents that survive from this period record the activities of elites – aristocrats and their bureaucrats, or rich merchants – so these letters will tell us new things about an important section of society in 17th-century Europe. These are the kinds of people whose records frequently don't survive, so this is a fantastic opportunity to hear new historical voices."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.