Srebrenica massacre 20th anniversary: Europe's worst atrocity since the Nazis [Photo report]

It is 20 years since the Srebrenica massacre, Europe's worst atrocity since World War Two. In July 1995, Bosnian Serb forces killed more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys in the eastern Bosnian enclave of Srebrenica, a designated United Nations "safe haven". About 15,000 men and boys managed to escape and fled through the woods, but many were murdered by the Serbian army who ambushed them, disguised as UN soldiers.

War had broken out in Bosnia in April 1992. The Bosnian Serb army swept eastwards. Srebrenica, a town of 36,000 where Muslims made up 75 percent of the population, was taken over by Serb troops but Muslims regained it after several weeks.

Early in 1993, Serbs started an offensive on Muslim-held areas. Srebrenica and Zepa became isolated enclaves deep in Serb-held territory. Muslims from the area flocked to Srebrenica and the population swelled to 60,000. They had little food, water or medical supplies.

In April, Srebrenica, Zepa and Gorazde in eastern Bosnia were declared three of six UN "safe areas". The United Nations Protection Force deployed troops and the Serb attacks stopped. But the town remained isolated and only a few humanitarian convoys reached it in the following two years.

Then Bosnian Serb President Radovan Karadzic ordered that Srebrenica and Zepa be entirely cut off and aid convoys be stopped from reaching the towns.

On 9 July 1995, Karadzic issued a new order to conquer Srebrenica. Troops surrounded the enclave and attacked the observation posts of Dutch peacekeepers, taking about 30 soldiers hostage.

The following day, Serbian forces started shelling Srebrenica. The Dutch threatened the Serbs with Nato air strikes if they did not withdraw by morning.

Another day later, Nato planes bombed Serb tanks outside Srebrenica. The Serbs threatened to resume shelling and kill the captured Dutch soldiers. Air strikes stopped and in the evening of 11 July, Bosnian Serb commander General Ratko Mladic entered Srebrenica.

An estimated 30,000 Muslim refugees packed around the Dutch peacekeeping base in Potocari, just north of Srebrenica, after Bosnian Serb forces seized the "safe area". Mladic sought to calm them, telling the crowd they did not have to be afraid.

Bosnian Serb forces put the frightened refugees on to buses to leave. Many of the refugees were evacuated to Kladanj, 50km (30 miles) away on the edge of government-held territory.

The UN noticed that most of the refugees arriving from Srebrenica were women, children, and the elderly, and became concerned about the fate of the men.

Over the week that followed the fall of Srebrenica, a total of about 8,000 men and boys from the enclave are estimated to have been killed by Bosnian Serb forces in detention or while trying to flee through the woods.

Men were crammed into warehouses, schools and barns in the area outside Srebrenica.They were shot and buried in mass graves.

Identification of the bodies is difficult: bodies were broken up by excavators that bulldozed them into mass graves. Bodies were also moved from the original graves to secondary locations to conceal the crime.

Forensic experts painstakingly work through what is left of the bodies found in the hundreds of mass graves that have been discovered in the area.

Every year on 11 July, the remains of those who have been identified over the past year are buried at the Memorial Centre in Potocari.

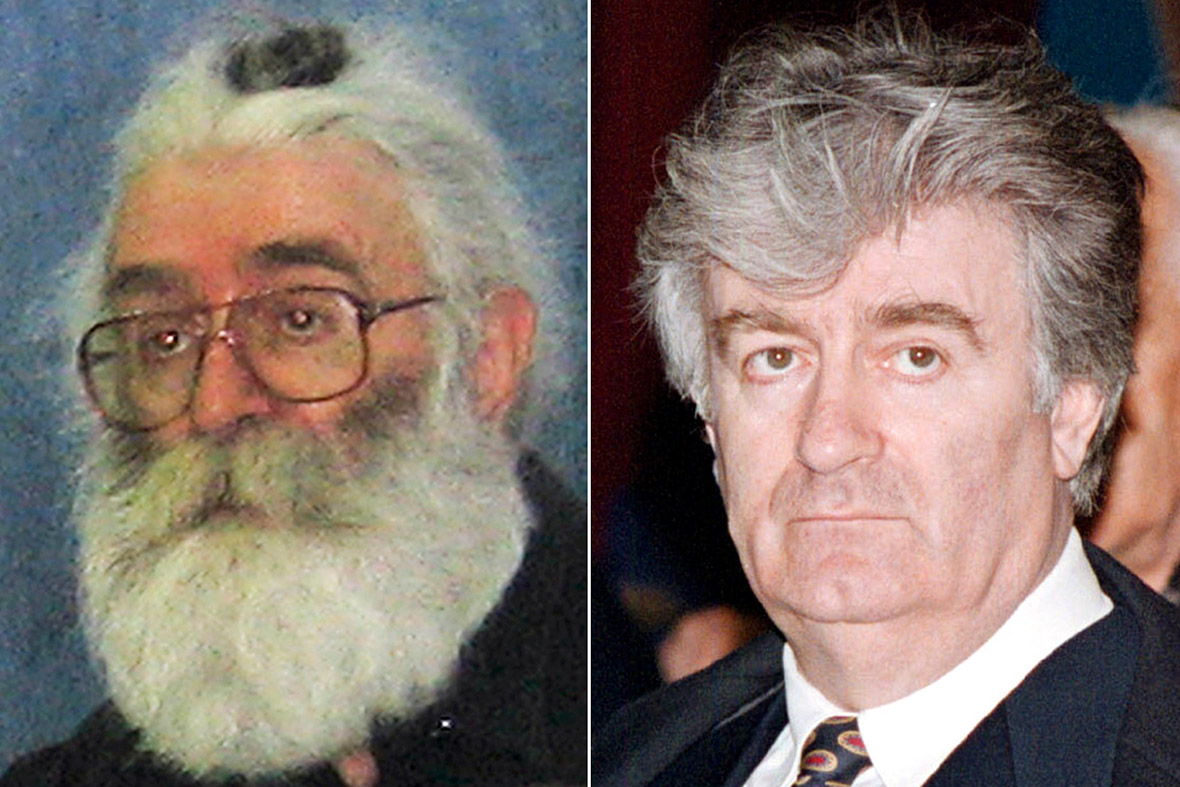

After the war, Karadzic went on the run and remained a fugitive for 13 years until he was arrested in Belgrade in 2008. He had evaded the authorities by working as an alternative medicine practitioner in a private clinic under the false name of Dragan David Dabic.

Mladic managed to evade justice with the help of Serbian army comrades and the Serbian state. He was finally arrested in 2011 after the election of reformist president Boris Tadic. Both Karadzic and Mladic are still standing trial at the United Nations war crimes tribunal in The Hague.

Twenty years on, the forests and farmland around Srebrenica are still yielding bones, but more than 1,000 victims have yet to be found.

Bodies were tossed into pits then dug up months later and scattered in smaller graves by Bosnian Serb forces trying to conceal the crime. Investigators believe at least one more big grave still eludes them.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.