Thames sewage: UK faces up to prospect of multimillion-pound EU fines

Gasping for breath and nibbling on floating faeces, fish twitch until they lilt on their sides and stop moving. A fisherman attempts to save just one dying fish by ducking it under the water in a vain effort to wash life-saving oxygen over its gills. Piles of dead fish surround him.

Fishermen in the riverfront neighbourhood of Barnes, west London, shot the images in a shocking video (see below) in June 2011 after 400,000 tonnes of raw sewage overflowed into the river from a Thames Water catchment. More than 100,000 fish died on that day alone, estimates the Thames Anglers' Conservancy (TAC), whose members shot the video.

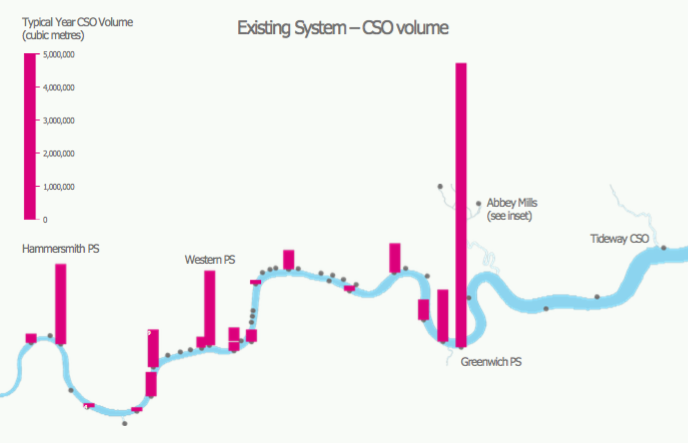

According to official numbers from Thames Water, 62 million tonnes of raw sewage was dumped into the river in 2014, up from 55 million tonnes in 2013. That's considerably more than the annual 20 million tonnes of spillage estimated in a 2005 study and Thames Water's current annual average figure of 39 million tonnes.

"After any sewage overflow, you will find the foreshore littered with condoms, sanitary towels, cottons buds and often human faeces," said David Harvey, chairman of the TAC, an independently funded group of anglers, who has seen the carnage first-hand.

London's sewage system bursting at the seams

To ease the strain, construction is about to start in the summer of 2016 on the £4.2bn ($6.4bn) Thames Tideway Tunnel — a 25km "super sewer" the width and height of three double-decker buses — flowing directly under the river.

But why has the amount of sewage released into the Thames increased so rapidly? And is the tunnel the right solution to fix the problem?

"The tragedy is that this is our premier river running though one of the world's most famous capital cities," said TAC's David Harvey, pointing out the irony of expensive restaurants and tourist attractions standing on one side of the river wall, while the other is covered in sewage.

London's sewage system is a well-built Victorian relic. Designed and constructed between 1864 and 1875 by civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette to waft away the Great Stink of 1858 and alleviate the cholera epidemics that claimed the lives of 40,000 Londoners between 1831 and 1866, it was a visionary structure. The sewer was built to accommodate a population of four million at a time when only two million people lived in London.

But today's population of 8.6 million is much more than planned. It has exploded from 7.4 million people in 2004, and in the next 20 years, the Office for National Statistics predicts London will grow beyond 10.5 million.

The weather plays a large part in the growing amount of sewage spilling into the Thames too. The period between December 2013 and January 2014 was the wettest since 1910. That's a problem when just 1.5 mm of rain flowing into catchments stuffed with sewage can send faeces sloshing into the river.

Climate change is only going to make this problem worse. Extreme rainfall is now seven times more likely as a result of the changing climate, according to Met Office scientists. But the amount of sewage dumped into the Thames in 2013-14 was "unusual" emphasises Phil Stride, a director of the Thames Tideway Tunnel project.

The 20 million tonnes estimated to be spilling into the river in Thames Water's 2005 Thames Tideway Strategic Study was just that, an estimate. "Until we started putting flow monitors on the discharge points in 2010," Stride said, "we weren't actually able to measure what was discharged."

A potentially very costly problem

Yet even under 2005 estimates, the Thames was so polluted that on 21 March that year, the European Commission sent a warning letter to the UK, saying the urban river's condition violated the EU's Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive — a law created to prevent pollution. After putting up a multi-year fight in the European Court of Justice, on 18 October 18, 2012, the UK was ordered to clean up the Thames or face multimillion-pound fines.

That threat is real. In November, the EU urged the court to fine Greece €15.9m for breaching the same directive. If the UK was asked to pay up now, the lump sum could total £684m, or £228m annually. That's calculated on the maximum daily penalty, which Stride pins at £625,000 per day.

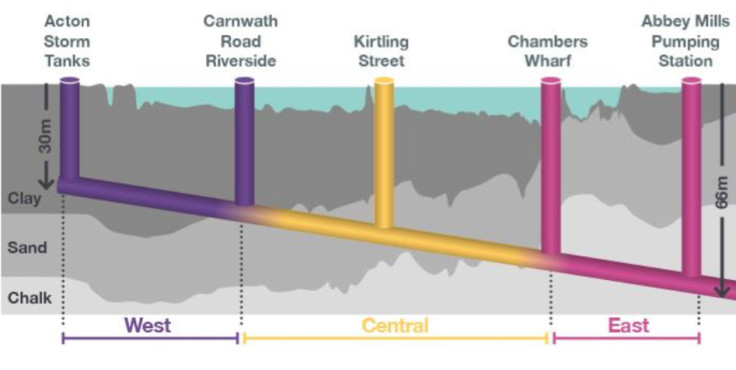

The super sewer is being constructed by several private companies and will begin with the excavation of three large shafts at strategic points across London. One of these is at Carnwath Road Riverside in Hammersmith and Fulham. The locations are "critical" to building the project, said Stride, because each lies at a crux in the geology under the river.

Crews will lower large boring machines into the holes fitted with unique drill bits capable of drilling the 7.2m diameter tunnel through either clay, mixed sand and gravel, or chalk under the riverbed.

In 2010, Thames Water said 7,000 basements in Hammersmith and Fulham and Kensington and Chelsea were at risk of being flooded with sewage during heavy rainfalls. Stride is convinced the Tideway tunnel would eliminate all this entirely. "[The tunnel] is 1.6 million cubic meters in volume. That whole volume will fill in a typical year about seven times," he said. "That's the volume of sewage that would otherwise have gone in the river."

New tunnel may not be the perfect solution

However, not everyone is so certain the tunnel offers value for money. Chris Binnie, the civil engineer who chaired the Thames Tideway Strategy Steering Group that advised the tunnel's construction a decade ago, is convinced there's a better way. Since his 2005 study was published, "several other methods of reducing spill frequency have become technically viable and proven as cost effective", he said.

He envisions green roofs and other water sensitive urban designs — such as water permeable pavement — to soak up rainfall, in conjunction with a Sustainable Drainage System. "My gut instinct is that such a combination would cost less than £1bn, thus saving £3bn," he said. What's more, Binne said, the Lee Tunnel — which will open in early 2016 to carry a mix of sewage and rain water from Abbey Mills pumping station to Beckton further down the river — promises to reduce annual sewage overflows to 18 million tonnes.

Binne's suggestions would be baked into urban planning rules for London. And they mirror alternatives to the Tideway Tunnel put forward in a 2011 study commissioned by the boroughs of Kensington and Chelsea, Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Richmond Upon Thames, and Hammersmith and Fulham.

"Sustainable drainage systems can significantly reduce local flooding, and can also future proof the Thames Tideway Tunnel" by reducing rainwater flowing into the sewer, Stride agrees.

But as the sole solution? "I would argue very strongly against it," he insists. "If we were to put in schemes and technologies that took out half of the storm water, you would still need an area 40 times the size of Hyde Park to put storm water. It's the volume of what we've got to intercept."

After 14.4mm of rainfall on 14 May, Thames Water issued an alert to rowers near Hammersmith that it had just dumped sewage into the river. If the dump happened on 11 April, Oxford and Cambridge's university rowing teams competing in the annual BNY Mellon Boat Race from Putney to Chiswick Bridge would have been mired in faeces.

Getting near the dirty water can lead to infection since it's filled with E.coli and other bacteria. A study of rowers on the Thames between January 2005 and March 2006 found 77% of their illnesses came after rowing in the wake of a sewage discharge.

On weekends TAC's David Harvey goes out fishing from Putney Bridge. But if there has been a concentrated discharge of sewage, there's little oxygen in the water for fish to breath and he won't catch much. He imagines a time soon when the Thames is a healthier place for all kinds of recreation in London. "It's a disgrace," he said, "it has taken this long to realise that something needs to be done."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.