Vietnamese refugee 40 years after fall of Saigon: 'I'll never forget'

When the forces of General Van Tien Dung rolled into Saigon on 30 April 1975 – effectively ending the Vietnam War – Anh Tu Nguyen was a 32-year-old journalist for Vietnamese newspaper Morning News, living in the southern capital with his wife and child.

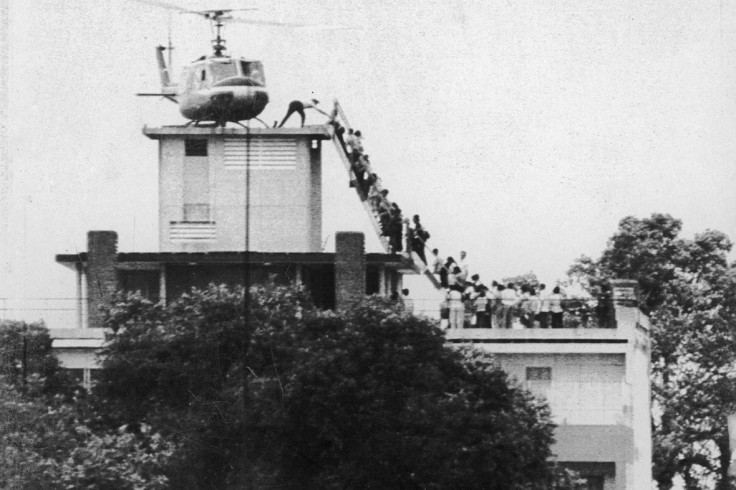

But as his friends urged him to join the 140,000 Vietnamese who were evacuated by the departing US army in the face of the Communist advance, Nguyen decided to stay put, believing the triumph of the north represented an opportunity for a unified Vietnam.

I told my friends that... I had never done anything useful for Vietnam – if the Communists killed me, at least I had tried to do something

"I was happy that the war had finished [and] that there was a chance to reunite our two peoples and [I felt] that together we could reunite our country. I told my friends that... I had never done anything useful for [Vietnam] – if [the Communists] killed me, at least [I had tried] to do something," Nguyen, now 72 and living in London, told IBTimes UK.

Massive ceremonies are being held in Ho Chi Minh City on 30 April and 1 May as Vietnam remembers the success of the north four decades ago. The victory ended a 15-year conflict in which up to three million Vietnamese and almost 60,000 American soldiers died.

But not all Vietnamese will join the celebrations. For the tens of thousands who fled Saigon in 1975 and the hundreds of thousands estimated to have left since, the victory of the Communist north is nothing to be celebrated. Four decades on, those refugees – including Nguyen – and their children refer to 30 April as "Black April".

"We do not celebrate that day," said Nguyen from his office in Deptford, where he helps to run the charity that supports the estimated 6,000 Vietnamese refugees who live in Lewisham. Many of these migrants started their perilous journey to Britain as boat people, leaving Vietnam in rickety vessels and eventually reaching Hong Kong before being granted asylum in the UK.

Nguyen's initial optimism about the new regime post-1975 did not last long. One of the first acts of the new government in the south was to order thousands of families to re-education camps, where they were promised food and a short stay of 10 days or so.

He was lucky enough to retain his job at the newspaper, which in the late-1970s sent him to cover a massacre of Vietnamese villagers by the Khmer Rouge, the Cambodian militia headed by Pol Pot. He filed a report from the scene that documented the gruesome atrocities that had taken place, which even 40 years later he recalls as "beyond barbaric. Like what Isis is doing today".

He said: "The Communists saw the report and they took it to mean I was on their side. They called me comrade and asked me to spy on my colleagues and bosses at the newspaper. I refused. I said I was a journalist [and] spying is not my job [...]. They didn't trust anyone."

I stick by the rules of journalism. I never let anybody change my work except my colleagues and my editor

But the regime did not give in. They continued to approach Nguyen and later posted a secret police official in the newspaper office. Then they began changing stories that journalists wrote to make them more favourable to the Vietnamese leaders.

"I stick by the rules of journalism. I never let anybody change my work except my colleagues and my editor," he said contemptuously.

Finally, when Nguyen wrote a seemingly innocuous feature about a team of southern engineers who travelled to the north to take part in an infrastructure project, he was once again pulled up by party officials who demanded to know where he had heard the news. They told him that his story embarrassed North Vietnam by implying they needed the south to carry out the work.

"I told them that the moral of journalism is to protect the source of the news," he said.

By then, Nguyen said, the game was up. Nguyen and his wife and child boarded a tiny dingy on the Vietnamese coast and paddled out into the Pacific Ocean with a group of other refugees. After four days, they were picked up by a ship carrying wood from Indonesia to Hong Kong, then controlled by the British. Ten days later they were granted asylum in the UK.

The days when the US and Vietnam were mortal enemies seems a long time ago now and in 2014, America overtook the European Union to become Vietnam's largest trading partner. US presidential candidate and former secretary of state Hillary Clinton has visited Hanoi, while thousands of American tourists travel to the country every year.

Vietnam has gone to great lengths to cosset the West, encouraging investment in its burgeoning manufacturing industry and welcoming American investment as a counter-balance to China, which has long sought to dominate its smaller South East Asian neighbour.

Dana Healy, head of the South East Asia department at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, told IBTimes UK that for many Vietnamese, the relevance of the war in their day-to-day lives is diminishing. However, she added, the war remains an important propaganda tool for the government, which still officially refers to it as the War of National Salvation Against the Americans.

"It remains an effective medium through which the Communist Party tries to bolster its legitimacy in the present day. Such commemorations help to preserve memories of the triumphant victory and collective sacrifice under the party's leadership when it is being slowly undermined by the market economy and consumer aspirations," she said.

For Nguyen, the commemoration marks the fact that little has changed in Vietnam since he left almost 40 years ago. He remembers a time before 1975 when health care and schooling was free. Now it beyond the reaches of most Vietnamese. Meanwhile, corrupt officials confiscate land for their own development projects and throw the owners in prison if they complain, he said.

Nguyen said: "Socialism? My God. We will never accept what they call socialism [...]. They do not represent people at all. The regime is a joke."

The 72-year-old does not approve of the flags, banners, jingoistic speeches and military marches that have marked the anniversary in Ho Chi Minh City but the 40-year anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War is not insignificant. Nguyen may not commemorate the fall of Saigon - but he will never forget it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.