Virtual reality sees promise in treatment of patients suffering from depression

Virtual reality has been used in new form of therapy to help treat people suffering from depression. Researchers at University College London used the technology as part of a study exploring whether 'virtual' therapy could help with mental health problems.

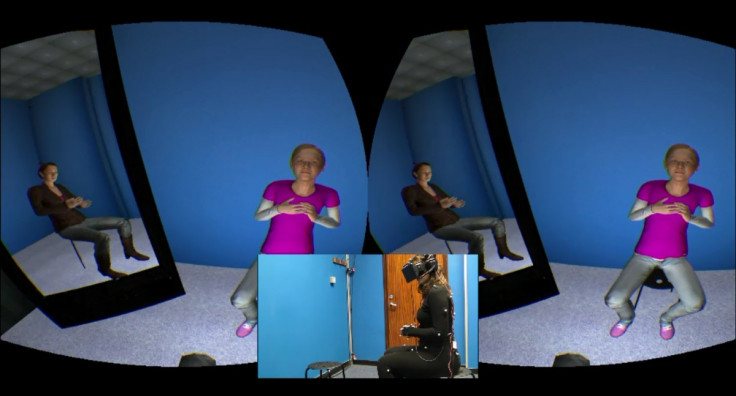

During the study, 15 men and women being treated for depression by the NHS were instructed to put on a VR headset. Through the simulation, the participants were confronted with a computer-generated reflection of themselves that mimicked their movements, before the avatar of a crying child was projected into the room beside them.

The patients were instructed to console the child by speaking compassionately to them using validation, redirection of attention and memory activation techniques, such as asking the child to think of a person that loved them and reminisce on a time when they were happy.

The roles were then reversed, with the participants taking on the avatar of the child and the simulated version of themselves appearing before them. They then heard the same words of comfort repeated back to them by their adult selves.

The eight-minute sessions were repeated three times at weekly intervals, with patients followed up a month after the therapy. According to UCL, the sessions proved effective at reducing symptoms of depression in nine of the participants a month after the trials, with four patients reporting "a clinically significant drop in depression severity".

Study lead professor Chris Brewin said the results suggested virtual therapy could help sufferers of depression be less critical of themselves. "People who struggle with anxiety and depression can be excessively self-critical when things go wrong in their lives. In this study, by comforting the child and then hearing their own words back, patients are indirectly giving themselves compassion," he said.

"The aim was to teach patients to be more compassionate towards themselves and less self-critical, and we saw promising results. A month after the study, several patients described how their experience had changed their response to real-life situations in which they would previously have been self-critical."

Virtual reality has previously been touted for its potential in treating phantom limb pain suffered by amputees as well as for predicting the behaviour of sex offenders.

Report co-author professor Mel Slater said that while the results were promising, more work had to be done in order to determine whether the virtual therapy was responsible for improving patients' symptoms. "We now hope to develop the technique further to conduct a larger controlled trial, so that we can confidently determine any clinical benefit," said Slater. "If a substantial benefit is seen, then this therapy could have huge potential. The recent marketing of low-cost home virtual reality systems means that methods such as this could potentially be part of every home and be used on a widespread basis."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.