What is IBM Watson? An evolution in artificial intelligence and why technology won't kill us all

IBM tells IBTimes UK about the future of cognitive computing and how AI isn't something to be feared.

In 2011, IBM sent its supercomputer Watson onto the popular American TV quiz show Jeopardy where it succeeded in matching wits with and beating two of the TV show's most successful players.

That was over five years ago, but if you ask members of the public to describe IBM Watson, those in the know will say that it's a huge great black mainframe computer that's incredibly smart. Yet according to IBM, that's where you'd be wrong – the computing giant is adamant that the future of artificial intelligence will not be one big scary digital brain, and technology is definitely not going to kill us off one day.

"When IBM Watson first came out, we used to think about it as a giant brain in a jar, but it's not that," John Cohn, an IBM Fellow in the IBM Watson Internet of Things (IoT) division tells IBTimes UK while showing us around IBM's new global IoT headquarters in Munich, Germany.

"It's a bunch of tools that you can use to compose systems that interact naturally with humans, learns from their situation, adapting and then applying that knowledge. It's not an easy philosophy to apply, but it can bring benefits to so many different industries."

Cohn, an inventor in the semiconductor industry, has been at IBM for over 35 years, and he says that computers are finally starting to reach the potential that was first envisioned for them back in the late 1970s due to the fact that technology and processing power have improved exponentially.

"The father of artificial intelligence, Marvin Minsky, was thinking about how you build systems that start to resemble real intelligence [back then], and finally all of the deep learning methods are now possible because of improvements in processing and memory," said Cohn.

He explains that the technology that drives graphics engines today on smartphones, video game consoles and computer animation software derives from IBM's purpose-built computers that dealt with a specific type of vector processing between the 1970s to 1990s.

"It turns out that in the last couple of years, things like recognising objects, all of those things we did for graphics processing [have] turned out to be a really, really good basis for doing what we now call 'deep learning'. Things [like image recognition] that were just pipe dreams five years ago, like recognising faces from photos, are now almost commonplace [on services] like Facebook and Google," he explains.

"Really low-cost electronics with super computing power, lots of bandwidth and an amazing computer science revolution... you can now put computing into anything. When people look back, they will see this as the tipping point. I'm talking as an old guy. I've been around for a long time and I've not seen this kind of evolution before."

Detecting patterns to help us make better decisions

So if Watson isn't a giant artificial brain that will be used to power our robot overlords, what is it then? IBM says it's all about cognitive computing. It's the ability to take completely "unstructured data" – i.e. data where there is currently no relevance or any reason to connect it to anything else – process all that data and detect new patterns so that humans don't have to figure it out all by themselves.

Big data analytics, whereby humans look at statistics from different aspects of their business all at once and then use it to make decisions, is already commonplace. But let's say you throw in something completely unexpected, such as a power surge or a major political event. This changes the data, and suddenly the computer doesn't have great advice to give.

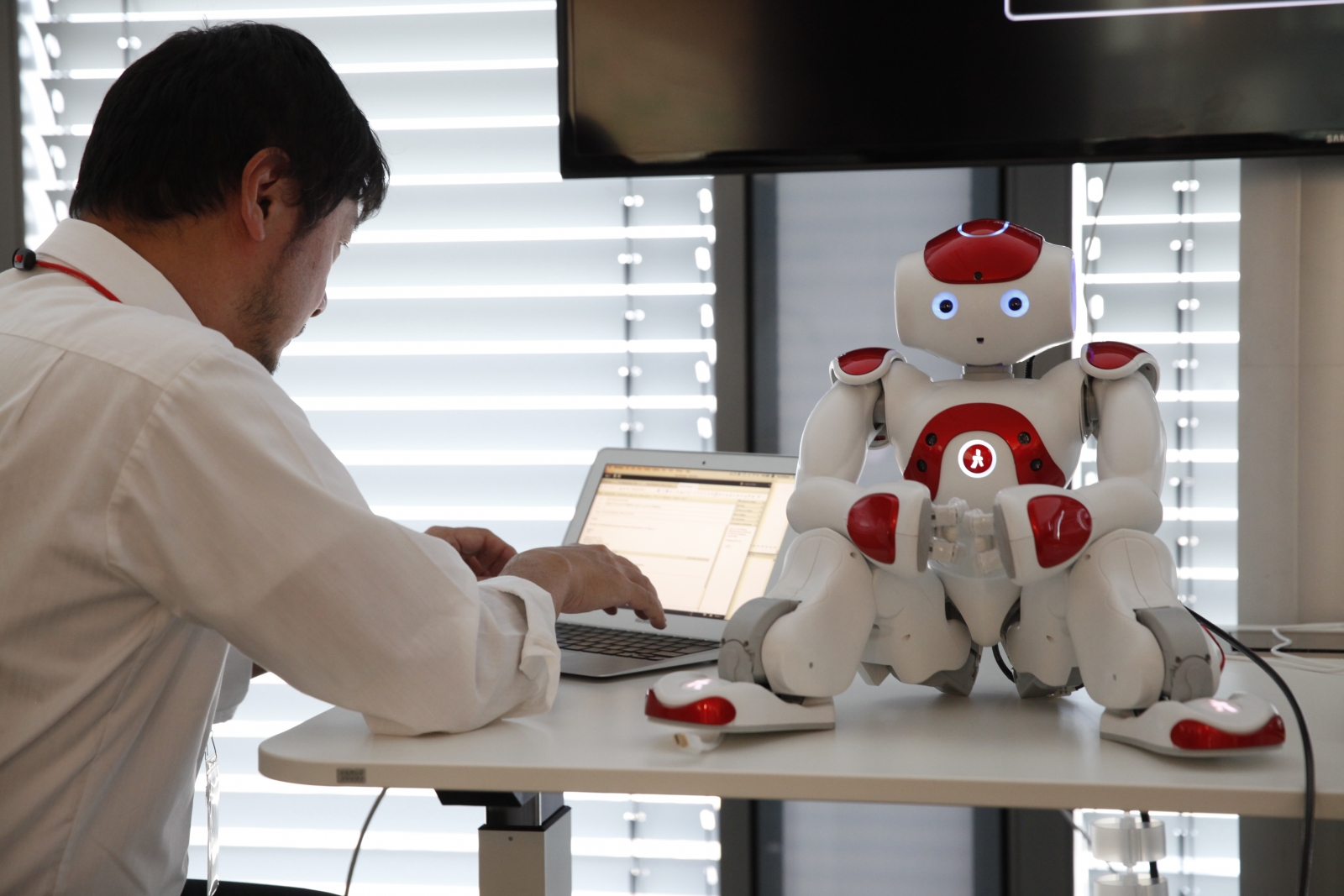

"Imagine that I'm working in a factory and I've got a robot that's working on something. I can have a human aide that the robot can ask for help. That can get the product into market half a decade faster. Humans are uniquely able to [process] unstructured data – all this crazy mixed up stuff where you don't know how things relate," says Cohn.

"Watson was the first system where anyone went out and tried to do deep learning on unstructured data. Focusing on the unexpected and being able to, in a very scientific way, [point out] what relates to what and under what conditions, is something that is distinctly human, but it can be automated up to a point. That's the basis of our approach."

The idea is that Watson is a set of tools sitting in the cloud that can be plugged into any dataset to figure out these nifty patterns. The data isn't stored by IBM – it sits in the customer's own data centre and Watson's job is to look at it and apply machine learning techniques, whether it's medical records or data being streamed from millions of smart devices.

What can you actually do with cognitive computing?

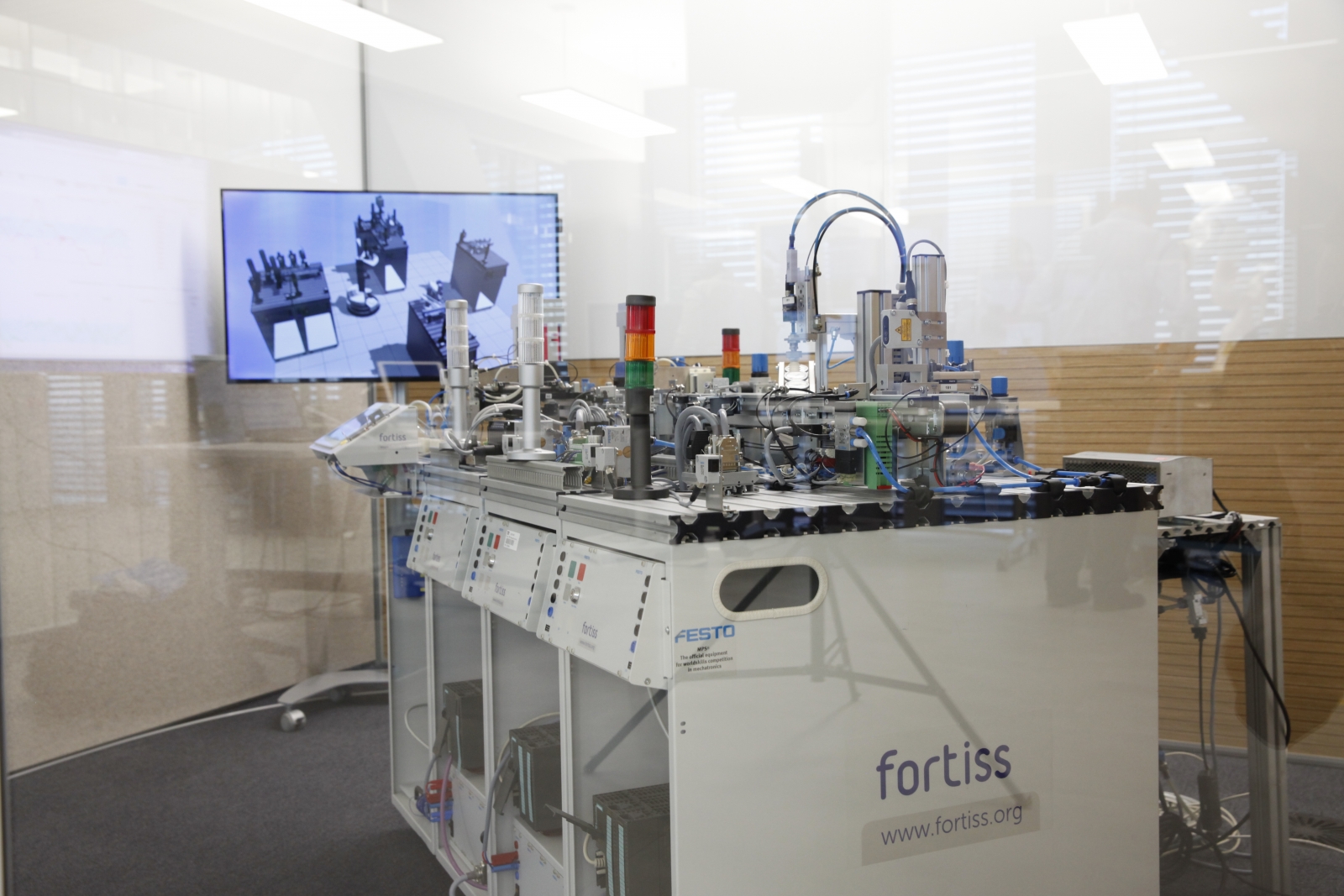

IBM's new IoT headquarters in Munich is basically a huge visual example of how cognitive computing can be useful if you provide it with data from the Internet of Things. The skyscraper is armed with sensors and the building's job is to constantly learn what the office workers want and adapt to their needs.

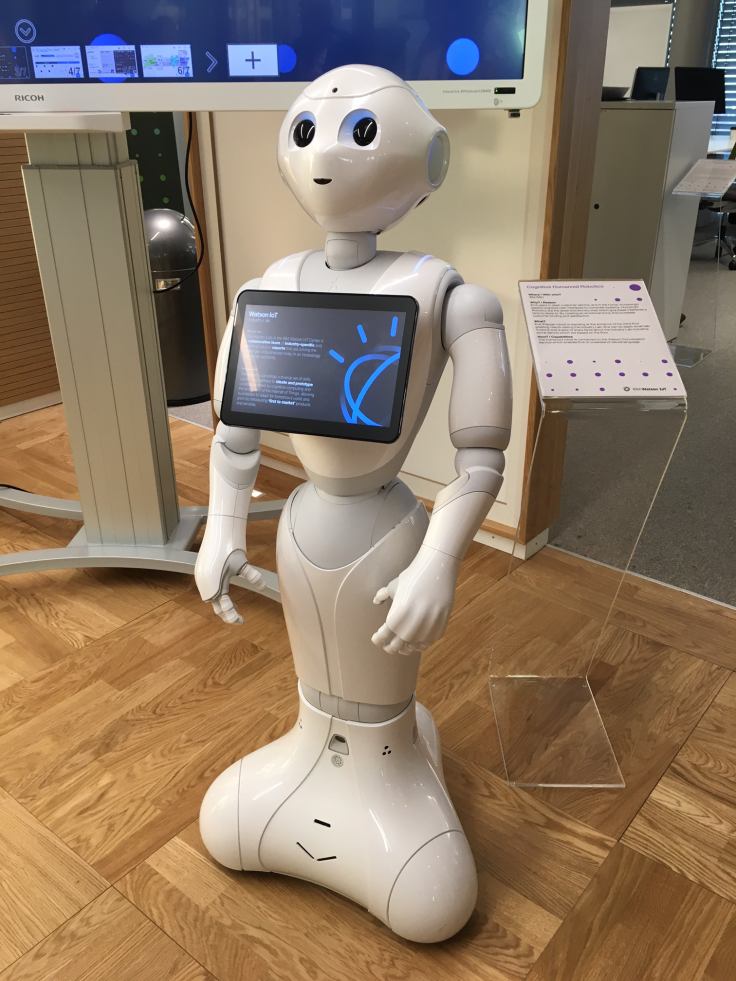

Let's say the sun is too bright between 11am-3pm on the east side of the skyscraper. Watson's human interface is Pepper the robot. An office worker tells Pepper to lower the blinds. Pepper issues the command, and Watson complies. But it also makes a note that the humans need the blinds down during those hours, so the next day, it starts the day with the blinds open, and then automatically closes them when it gets to 11am.

Similarly, if you were to book a meeting room under your name. Over time Watson figures out that you need the lights to be a certain brightness, and that you prefer a specific temperature, because in the past its sensors have picked up when you start to shiver.

Now forget about the building. Take Watson and apply it to the Internet of Things, and according to IBM, you can then use it to enable a huge number of really interesting and helpful features in existing technologies.

Take for example your car. We don't have self-driving automobiles yet, but your car does have a computer in it. With Watson's help, now if you need help using the car, instead of pulling over to read the manual, you could talk to your car and ask it the question.

The car manufacturer sends the audio file containing your question to Watson, which figures out what you said, then checks for the answer in the manual database and then sends it back so your car can respond to you verbally.

Then there's customer relations. Nowadays companies are finding that customers prefer to use chatbots instead of talking on the phone to customer service representatives, and those chat logs provide a wealth of additional information that is useful to making sure customers stay happy.

In the field of medicine, IBM is trying to process huge amounts of information from scientific literature, and then combine it with patient models and similarities, so that within a few minutes, a doctor can be offered the best possible solution to treating a patient with a particularly tricky condition.

A sneak peek inside Watson's extensive toolbox

Cognitive computing is a loaded word. It sounds cool, but what does it actually entail?

IBM's artificial intelligence experts reveal that they are using many different types of machine learning to get the job done, from deep learning for image and video analytics; graphical networks for genomics; random forests for document ingestion; clustering for patient modelling; generative and adversarial neural nets for modelling chemical reactions; Markov modelling for understanding graphics [such as] technical diagrams; and an array of computer vision technologies for robotics.

"We are using many different algorithms and data analytic streams. The complexity of the problems we get from our customers means we cannot afford to have a favourite machine learning algorithm," says Costas Bekas, manager of the foundations of cognitive computing at IBM Research in Zurich. "There is no silver bullet."

And it's not just all about having an answer for the customer. Bekas stresses that all the answers and solutions Watson produces have to be auditable, because the decisions that are made using its data are so important. Therefore, no answer is allowed to be like a "black box", whereby you throw a bunch of data in and an answer comes out, but the human doesn't know why.

"When we get an answer from a cognitive system, this always comes back with an explanation as to why it gives a certain decision proposal. The reason is we want to have machine learning that is explainable," he says.

"I think that systems that are able to understand seeing and hearing the world as we are, are for the near term. Longer term, we will see systems that can automatically generate knowledge models, but that is beyond the five-year horizon."

Humans aren't going anywhere

Although some people are excited about a technologically advanced future full of robots, others are hesitant. The concern is that artificial intelligence will usher in the singularity, a sci-fi concept describing the moment when every aspect of human civilisation changes so drastically that its rules and technologies become completely alien to previous generations, such as the change from medieval times to the industrial revolution in the early 1900s.

Humans are at the centre of cognitive computing. The system is always helping the human, the human is augmented by the system. Cognitive computing is not to replace people.

But IBM is determined that humans will always have their hands on the reins, and rather than robots taking over our lives, artificial intelligence will serve only as a helping hand.

"Humans are at the centre of cognitive computing. The system is always helping the human, the human is augmented by the system," Bekas insists. "Cognitive computing is not to replace people. It is to make each and every one of us far more productive, to give more tools to the people, so we become free of the tyranny of the data and we have more opportunities for everyone."

What IBM seems to be saying is that artificial intelligence doesn't have to be a curse, despite the increasingly dire warnings that important figures like Stephen Hawking continue to make about technology one day killing off the human race.

"When you starting thinking about it, processes like driving a car, flying an aeroplane, driving a train, assembling a car, diagnosing a human – a lot of those things can become highly automated. There's a level at which something becomes so automated that you can't trust it, but if you allow a human to be at the centre of it, which is what we mean by cognitive, then there's a lot you can achieve," says Cohn.

"Our approach of putting a human where a human should naturally be, and having it interact with a physical system, like an aeroplane, a car, a surgical robot, a house, a factory, makes a lot of sense."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.