Who was Hannah Arendt, the political philosopher who wrote about the origins of totalitarianism

The work of the Jewish thinker who coined the phrase 'the banality of evil' is enjoying newfound popularity.

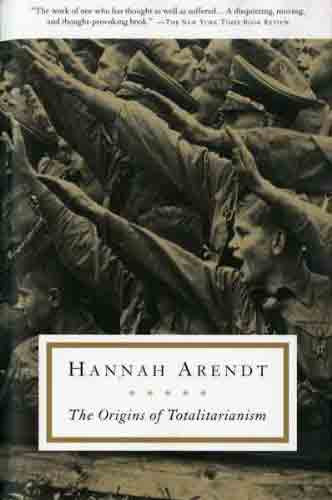

While George Orwell's 1984 has recently become an Amazon US bestseller, readers who seek a more challenging read on authoritarian regimes have turned to German-born philosopher Hannah Arendt, whose work The Origins of Totalitarianism now features in the top 20 bestselling books in politics and government – just below the US Constitution.

In the wake of Donald Trump's ban on seven Muslim-majority countries and refugees, Arendt's understanding of politics is as timely as ever, as she experienced first-hand what it meant for a society to take an authoritarian turn.

Born into a secular Jewish family in Germany in 1906, Arendt was able to witness first-hand the descent of the country under Nazi Socialist rule. Arendt was stripped of her German citizenship during the Second World War. She had left the country in 1933 and had sought refuge in various countries in Europe before arriving in Portugal, from where she crossed the Atlantic and landed in New York in 1941 as a stateless refugee.

It is no wonder that her writing is being increasingly appreciated in the wake of increased nationalism, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia.

According to Roger Berkowitz, director at the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and the Humanities at Bard College, Arendt would have seen Trump's presidency as an element of totalitarianism.

"She thinks that one of the core elements of totalitarianism is that it's based in a movement. A movement doesn't actually pursue achievable policies because if you achieve the policy, the reason for the movement is lost and the movement will lose its energy," he told Deutsche Welle in December, referencing Trump's claims to be part of a "movement", which were repeated during his inauguration speech.

But, Borowitz warned, Arendt would suggest that the worst threat is an increased cynicism towards democracy due to the constant doubt over what is "real" and what is "fake" political discourse. "The real challenge from an Arendtian point of view over the next four years is to insist on the meaning of public discourse and on the importance of public institutions and not allow cynicism to take over," he said.

Having reflected about her experience as a refugee in the 1943 We Refugees essay, Arendt continued her academic work as a visiting scholar. She published two of her most important works in the 1950s: The Origin of Totalitarianism in 1951, which traced back the origins of Stalinism and Nazism to anti-Semitism and imperialism; and The Human Condition, in 1958, which discussed her theory of political action.

Around that time, as the US was targeting communism as a major threat to its way of life, the FBI opened a file about her after the father of one of her students denounced her for being "very dangerous to the best interests of this country". He stated Arendt "was advocating a totalitarian philosophy in her political courses" although "he could not say" whether she was a communist.

In 1961, Arendt was sent to Jerusalem to report on the Adolf Eichmann trial for the New Yorker. It was in relation to the trial that she coined one of her most well-known phrases, the "banality of evil".

Eichmann was a lieutenant colonel for the SS and he was believed to be one of the Holocaust's masterminds. He fled Germany after the capitulation of the Nazi regime, but his efforts to escape justice failed when the Israeli secret services traced him in Argentina and effectively kidnapped him to face trial in Israel.

Arendt came to disagree with the view that Eichmann was a cruel monster. She was actually horrified to discover that he had simply been a man who was following orders, justifying his behaviour by invoking Immanuel Kant's definition of duty to explain his actions, as a law-abiding citizen in a country where the moral and the law resided in the person and orders of Führer Adolf Hitler.

The philosopher was frustrated with the trial, which she saw as a missed opportunity to investigate properly the human responsibility behind the Jewish persecution and extermination. She was particularly critical of the omission of any self-criticism to the failure of Jewish community leaders to understand the threat Nazism posed to them, a topic she had discussed in the Origin of Totalitarianism.

In the book, Arendt suggested that the Jewish people had often been too blind to the threats to their survival and opted for cooperation with authorities as an act of self-preservation, seemingly unaware of the consequences this may bring.

Her controversial view of the trial did not win her many friends. "There are many letters both pro and against Arendt which testify to the depth and the bitterness of the controversy that sprang up immediately after the publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem," noted the Hannah Arendt Center at the New School University.

Some criticised her for implying the Jewish people were complicit in their faith – accusations she flatly rejected. "Nowhere in this book did I accuse the Jews of failing to resist" she said. Her coverage of the trial and the ensuing controversy was also the topic of a biopic on the philosopher released in 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.