Why Europe is resorting to China for its penicillin supply

With three of the world's four manufacturers for penicillin's core ingredient based in China, countries source from companies that do not always adhere to European standards.

Countries hit hard by shortages of penicillin are increasingly turning to Chinese companies as the majority of the factories still producing the drug are based in the country.

Today, only four companies in the world are responsible for the global supply of the active ingredient in the antibiotic benzathine penicillin G and three of them are located in China.

Benzathine penicillin G is the first-line therapy for syphilis and rheumatic heart disease. However, shortages of the antibiotic have been reported in at least 18 countries over the last three years, including in Europe and in North America.

For ensuring access to this essential drug, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, South Africa and India are some of the countries sourcing benzathine penicillin G from Chinese companies. Others, such as England and Scotland, buy the medicine from European drugmakers made with ingredients from China.

Two years ago, as Portugal was struggling after months of shortage of the drug, Portuguese drugmaker Laboratórios Atral S.A. turned to Asia after its former European supplier made some changes - which Atral says are incompatible with its formulation process.

Atral says none of the companies they evaluated in China had the full set of documents demanded by the European Union, such as a certificate of suitability or the Active Substance Master File (ASMF), where a producer details its manufacturing process.

But the European drugmaker had no other option, so it worked with a Chinese manufacturer to bring together a package of information in line with the EU legislation. Atral says it has audited the Chinese manufacturer to verify its quality standards, but it doesn't want to disclose the company's name, saying this is "confidential business information".

The Portuguese product with the Chinese ingredients is also sold to at least five other nations, including Scotland and England.

But the limited number of manufacturers is not the only problem. A few years ago, one of the four global suppliers, North China Pharmaceutical Group Semisyntech Co. Ltd, was banned from the European Union for bad manufacturing practices, reducing even more the number of producers qualified to sell the drug.

"It is not easy. There are a few producers and, of those that are in the market, one is banned and the others don't have complete documentation," says Eduardo Oliveira, regulatory affairs director of Atral.

In November 2014, inspectors from the France's drug agency who were visiting North China found falsification of documents, lack of data integrity in the quality control laboratory and risk of contamination in the medicines assembled in the plant, located in the city of Shijiazhuang, Hebei province.

The French authority recommended the company to be prohibited from supplying different types of penicillin to EU members. Following the inspection, both Spain and Germany withdraw certificates of good manufacturing practices issued to North China in the past.

Severe penicillin shortage

In less regulated markets though, such as Brazil and South Africa, the penicillin shortage was so severe that both countries allowed North China to supply the medicine to their territory despite the serious quality issues found at the site.

"We have been buying it for 30 years, it's an essential product. It is surprising that there are so few manufacturers left," says Michiel de Goeje, director of quality affairs from IDA Foundation, a non-profit organisation based in Amsterdam that distributes medicines to low and middle-income countries.

Another major issue is that these companies produce only 20% of what they could, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), because benzathine penicillin G is cheap and off patent. The medicine's perceived low margins also keeps manufacturers away from entering the market, perpetuating the problem.

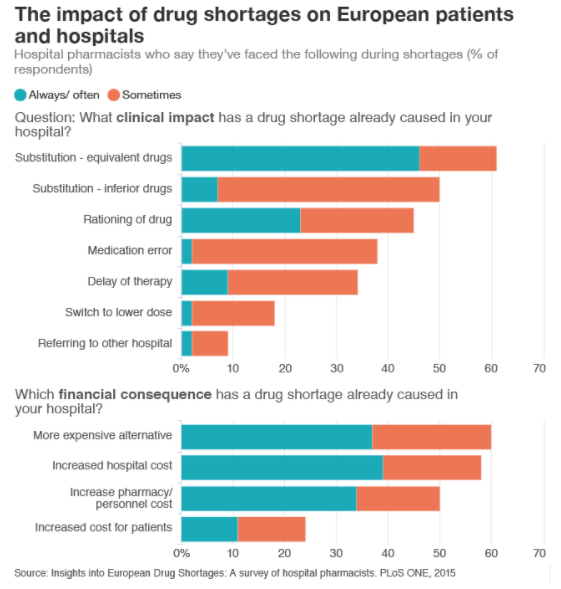

For patients, shortages of essential medicines such as benzathine penicillin G mean they are sometimes treated with less efficient and more expensive drugs. According to a 2015 survey with European hospital pharmacists, half of the professionals said patients were given inferior drugs during shortages. More than a third said shortages had led to a medication error.

And these shortages are not rare. "Hospital pharmacists in Europe will usually face difficulties in sourcing a medicine that is not immediately available in their country," notes Steve Glass, chief commercial officer of Clinigen for North America and Europe, a company that supplies hospitals with medicines.

Shortages are fuelling antibiotic resistance

Benzathine penicillin G is the first-line therapy for syphilis and rheumatic heart disease, but when doctors can't find enough of the antibiotic, they resort to alternative medicines that can be more expensive and less effective. That is in turn fuelling antibiotic resistance, one of the biggest threats to global health, experts argue.

"The shortage of penicillin complicates syphilis treatment. If the medicine is not available, clinicians are forced to use second-line drugs, such as azithromycin," says Lola Stamm, a microbiologist at University of North Carolina, author of a 2016 article on resistant syphilis.

Azithromycin, usually given as an oral antibiotic, has been associated with the rise of resistant strains of syphilis and this is why the infection is becoming so much harder to treat, according to a paper published in Nature last December.

In the case of rheumatic heart disease, that affects 33 million people worldwide, patients need monthly injections of penicillin to control the disease, sometimes as lifelong treatments. When penicillin is not available, doctors resort to azithromycin as well.

However, resistant strains of the bacteria related to the condition have risen in recent years, fuelled by the overuse of azithromycin.

"When injectable penicillin is not available, oral antibiotics are used sometimes, but these are less effective and may have unintended effects on antimicrobial resistance," says Dr Rosemary Wyber, deputy director from global advocacy RhEACH, who coordinated a report on the availability of benzathine penicillin G last year.

This is a major public health threat worldwide. A recent report commissioned by the UK government estimated that 700,000 lives are lost annually to drug resistance. It warned that that resistant organisms will kill as many as 10 million people a year by 2050, with a loss of up to US$100 trillion to the global economy, if the problem is not addressed now.

Ensuring old drugs are available is a way of tackling the spread of resistance. However, there is often a shortage of these medicines, because they are cheap and offer little profit.

A recent study on shortages of old antibiotics in Australia, North America and Europe found that several old medicines were not available in most of the countries surveyed, mainly due to economical reasons. Benzathine penicillin G, which costs as much as US$ 2 a vial, was unavailable in 20 of the 39 nations surveyed.

"When you don't have penicillin to treat syphilis you use second-line drugs, and then the problem of resistance arises. That is not good for the patient in terms of efficacy and it is not good for the world because this selects more resistance," says professor Céline Pulcini, who coordinated the study.

Pulcini says new drugs should be developed but old ones also need to be made available for patients. "There is a very strong focus on new drugs but nothing much is said about existing ones. And that is basically because there is no much money in this market. The price is so low that nobody is interested", she explains.

"It must be a top priority for governments to solve this. We need new businesses models and incentives to have old antibiotics in the market, otherwise we will just lose these drugs," she adds.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.