You or the pedestrian: Ethics of autonomous cars making emergency decisions to save lives

The complexity of programming a self-driving car pales into insignificance when compared to the ethical issues they raise - chiefly, what the vehicle should do when faced with a no-win situation. Should it crash and injure or potentially kill its owner to save a pedestrian?

This scenario is one developers of autonomous cars must tackle before they can be let loose on public roads, and while the ultimate goal of having a road network populated exclusively by self-driving vehicles could be accident-free, this is little more than a fictional utopia.

An ethical minefield

For now, autonomous cars will have to fit in with regular drivers; drivers who may be tired, drunk, lost, or simply not paying attention. These, mixed with barriers, lampposts, trees and buildings - and equally distracted pedestrians - make for a physical, legal and ethical minefield.

Researchers are beginning to tackle the crux of the matter - if an autonomous car is faced with a no-win situation which it cannot avoid without impact, what should it do?

An autonomous car is likely able to react more quickly and stop in a shorter distance than a human driver; it is also likely to have a better understanding of road and traffic conditions at that precise moment, and it will not get tired or distracted. But what about its reasoning?

Should it react to save its owner and passengers at all costs, or should it choose to hit a wall to save the life of a child in the road? Should it take into account the number of potential injuries or deaths, and who they are? Should it calculate the forces involved and seek out the softest target to protect its owner? Who should programme the vehicle to act this way, and should it be allowed to learn from its own experiences to change future decisions?

Tackling the issue is Ameen Barghi, of the University of Alabama. "Ultimately, this problem devolves into a choice between utilitarianism and deontology. Utilitarianism tells us that we should always do what will produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people."

As a real world example, consider travelling along a country road used by all manner of vehicles and with trees and walls along its sides. A group of children run out from behind a row of trees along the roadside and into the autonomous car's path; the only two options are to hit the children, or swerve and hit either the tree or an oncoming truck. An utilitarian approach would crash into the truck or tree to cause the fewer injuries.

On the contrary, vehicles programmed to take a deontological approach would not swerve into harm's way because that would be the car actively choosing to injure or kill its owner. The driver has been deliberately killed and they had no control over it, but who is responsible?

If a utilitarian approach is taken, this is split into rule utilitarianism and act utilitarianism. The former, Barghi explains, "says that we must always pick the most utilitarian action regardless of the circumstances." This means counting up the number of lives at stake and taking the action which will result in the least deaths; in the above example, that would mean killing the driver to save the children.

Alternatively, act utilitarianism "says that we must consider each individual act as a separate subset action," and it would be impossible to programme a computer to know how to act in every possible eventuality.

Autonomous cars could use their dozens of sensors to calculate the weight, speed and momentum of vehicles around them, thus always having an escape plan if a no-win situation arises; the plan would involve taking the path of least resistance, such as hitting a smaller car instead of a truck. But what if this means avoiding a larger, safe, modern car to hit an older, smaller, less safe vehicle and injuring its passengers?

'Similar to military weapons systems'

Dr Patrick Lin, director of ethics at California Polytechnic State University, wrote in 2014 that developing such a system "seems an awful lot like a targeting algorithm, similar to those for military weapons systems... this takes the robot-car industry down legally and morally dangerous paths.

Lin suggests that autonomous car makers would programme their cars to hit vehicles with a good safety record - like Volvos - and to hit motorcycle riders with helmets instead of those without.

"Crash avoidance algorithms can be biased in troubling ways, and this is also at least a background concern any time we make a value judgement that one thing is better to sacrifice than another thing."

Lin says such a system would give bikers a reason to not wear helmets and persuade car buyers away from models which are more likely to be hit because of their safety record.

A random decision - feeling lucky?

Even more terrifying is the thought of autonomous vehicles giving themselves a 50/50 choice in the event of an unavoidable collision. "A robot car's programming could generate a random number," Lin suggests. "If it is odd, the car will take one path, if it is even, the car will take another path. This avoids the possible charge that the car's programming is discriminatory against large SUVs, responsible motorcyclists, or anything else... a random decision also better mimics human driving, insofar as split-second emergency reactions can be unpredictable and are not based on reason".

Herbert Winner, head of automotive engineering at Darmstadt University of Technology, agrees, telling the Financial Times that a "random outcome generator" could be a solution to no-win situations. "If you don't wish to advantage a particular group, [this] is the most fair option," he said.

But with 90% of car accidents blamed on human error, programming autonomous cars to react like we do in emergency situations perhaps isn't the best approach.

Winner added: "When an accident does finally happen, someone will say; well, a human wouldn't have caused that accident. People accept that we all make mistakes, but robots are expected to be infallible."

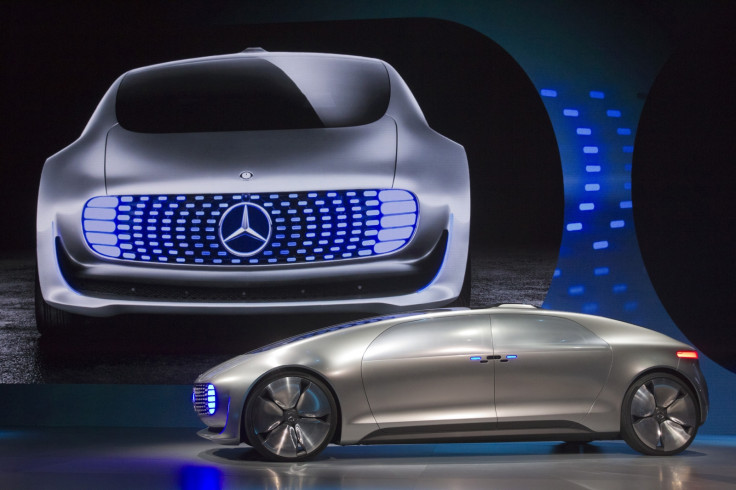

For now, these robots are unable to control cars enough to result in the collisions outlined above - even automatically swerving around a suddenly slowing car on the motorway is not yet legal, despite Ford and others having already created such systems. But Google, Mercedes and many others see a future where entirely autonomous cars will drive in city centres and on motorways - and on every road in between, in all types of weather - but until they can, ethics will play a part significantly more valuable than sensors and processors.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.