The first Zeppelin raid on Britain and the birth of the Blitz spirit

Bombs should never have fallen on East Anglia on the night of 19 January 1915, during the First World War.

But civilians living in the area were to become the first in Britain to suffer the new terror of an air raid and among the first victims in a new age of total war.

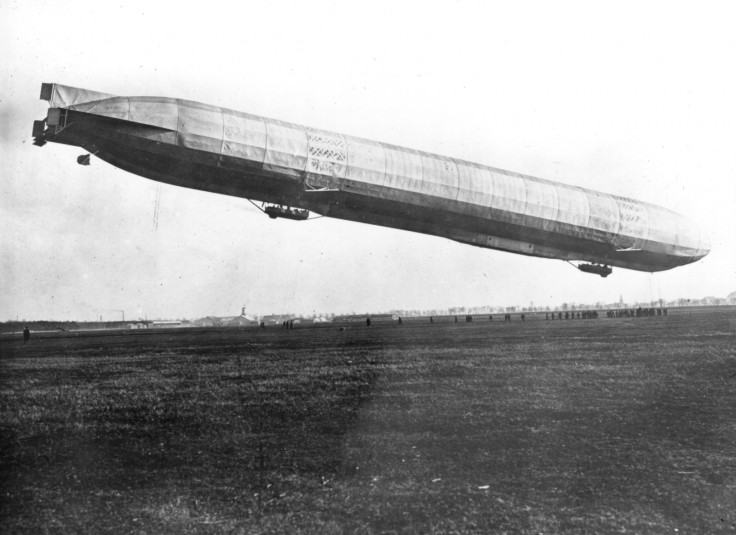

Two German Zeppelins – L3 and L4 – had set off from their base at Fuhlsbüttel, Hamburg, in the morning and slowly dragged their bloated frames through the sky towards England. Their target was Humberside, home to key wartime military and industrial infrastructure.

Both airships were over 500ft long, packed with two-thirds of a tonne of bombs and incendiary devices, carrying enough fuel to fly for 30 hours and capable of a top speed of 85mph.

There were two crews of 16 airmen operating in gondolas underneath the ships, above each of which was an enormous balloon packed with 750,000 cubic ft of purified hydrogen, a highly flammable gas.

A third Zeppelin, L6, had also taken off, but was forced to turn back early after encountering technical problems.

In the darkness over the North Sea, and with poor weather conditions, the German pilots abandoned their original target of Humberside. They headed instead for the East Anglian coastline.

At 6.40pm, two lights were spotted amid the fog above the sea. At first they were thought to be stars. Yet they were moving towards the land. Then it became clear: they were the navigation lights of German Zeppelins.

L3, piloted by Captain Lieutenant Johann Fritz, made its move for the seaside town of Yarmouth and dropped nine bombs on the town's St Peter's Plain area. Houses, a steam drifter and a church were all damaged. Two people – Martha Taylor and Samuel Smith – were killed in the blasts. Several were injured.

"It was just one big bang, one big crush. It could have landed on our house," said Florence Wortley-Waters to the BBC in January 2011 when she was 102.

"We had been to my aunts and was walking home after tea in the evening. There was this sound in the sky and my mum said: 'That's a Zeppelin.' It followed us right to my mother's front door.

"It was frightening, very frightening for us as children."

Wortley-Waters, one of the last surviving Britons with memories of the Zeppelin raids on the country during WWI, died a month after giving the interview.

"They said that a Zeppelin followed a train in at each station, came right over here and followed a roadway," said Cliff Temple, a Yarmouth local, on a 1972 BBC documentary about the raid.

"I was a small boy at the time, waiting up for dad who was coming home on leave. Hearing a nasty drone, drone, drone in the sky we wondered whatever it was.

"So I opened the door and there above us was a huge cigar-shaped object. Underneath we saw two gondolas and men walking about on them."

While L3 unloaded over Yarmouth, L4, under the control of Captain Lieutenant Count Magnus von Platen-Hallermund, floated along to King's Lynn dropping bombs on wherever there were lights on the ground.

The most damage was done to King's Lynn, where two were killed – Percy Goat and Maud Gazeley – as houses were bombed.

Again, several were injured, some of them seriously. The pump house at the docks was destroyed. Damage in King's Lynn totalled £7,000 – or £630,000 in today's money.

"It was about between 10 and 11, I think when this Zeppelin came over and it made a sort of a zoom-zooming noise," recalled 78-year-old Olive Smith, speaking to the BBC in 1972, whose sister was Maud.

"Then next thing we heard was this bang. And of course they had had word in the town that they were over at Yarmouth, but they phoned through to the police but the police never took any notice of them.

"So of course the lights were still all on you see. And then when this bang came the lights all went off.

"My father didn't know where my sister was, and my sister had got killed, and he hunted all around. Of course it was pitch dark, you couldn't see a thing, and eventually he found out she was in this house."

Her father had to wait until the morning before he could pull his daughter's body from the rubble of the house.

In the weeks after the raids, the government put up notices to let people know they were entitled to compensation and how they could claim.

On the death certificates of the civilians killed would appear a phrase never before seen for those who died on the British mainland. The cause of death was "from the effects of the acts of the king's enemies".

The war in the air

Britons knew this was coming. The successes of the Wright Brothers in 1903 had made the impossible possible for man: flying.

Alongside this, German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin was developing the airship that would bear his name and rain down horror on to the people of England during the First World War.

As with all technological developments, there are dark sides as well as light. Inevitably, flight would be used militarily and everyone knew it.

What's more, it removed the natural barrier of protection on which Britain had relied on for so many years.

Before, enemies would have to sail to Britain to bring war to the mainland but the Empire was known for ruling the waves with the best navy in the world.

Now they could fly over instead and there was very little the navy could do to stop them. Britain, it appeared, was not an island anymore.

HG Wells, the famed and prophetic science fiction author, drew on these fears for his 1908 novella The War In The Air, a tale of the apocalyptic potential of flying machines that foresaw fears of a nuclear holocaust at the fore of a Cold War world's minds.

"And now the whole fabric of civilisation was bending and giving, and dropping to pieces and melting in the furnace of the war," Wells wrote.

Dr Brett Holman is a lecturer in Modern European History at Australia's University of New England. He is also the author of The Next War In The Air: Britain's Fear Of The Bomber, 1908–1941, a study of the country's perceptions of air raids in the early years of aviation technology.

"It was widely accepted before 1914 that attacks from the air were possible, even probable," Holman told IBTimes UK.

"Small scale bombing had already taken place in wars in Libya and the Balkans, and both science fiction writers and more serious experts speculated freely about what might happen in the future.

"Also, it was well known that the German army and navy were building Zeppelins, which had the range to reach targets in Britain and the capacity to carry a significant number of bombs; but also that Britain had no substantial airship fleet of its own.

"In early 1913 these factors combined with suspicions about German spies and invasion plans to cause an airship panic: people all across Britain thought they saw or heard Zeppelins actually flying in the skies above them.

"These 'phantom airships' or 'scareships' weren't real; but they're a good indicator of just how unsettling the British people found the German Zeppelins to be. And indeed phantom airships were seen again in the first few months of the war, when Zeppelin attacks were thought to be imminent."

The aftermath

Naturally, the press carried photos of the bombing damage and stories of what had happened on 20 January 1915. It drew on all the wartime imagery of the Germans, referring to the Zeppelins as "baby-killers". But the reaction was not as hysterical as it could have been.

The Times, Britain's paper of record, carried no report of the bombings the following day. Instead, it carried a warning about air raids after failed German attempts over the south coast prompted the Metropolitan Police to advise people: "Keep indoors or get there."

On 21 January, The Times addressed the bombings of two nights previous. There was a defiant report by "by our naval correspondent" on page five, titled "Motives of the raid".

"The duties of aircraft are scouting and the destruction by means of bombs of objects of military usefulness and importance," said the report.

"To these the Germans have added a third, which they term 'frightfulness' – raids which by the murder of non-combatants and the destruction of private property may strike terror into the inhabitants of a country in the hope that, by setting up a state of nervousness, an influence may be exerted on the progress and direction of the war.

"In our case, of course, the hope evidently is that the flow of reinforcements to the Continent may be stopped, whereas in point of fact the excursion of Tuesday is more likely to have exactly the opposite effect."

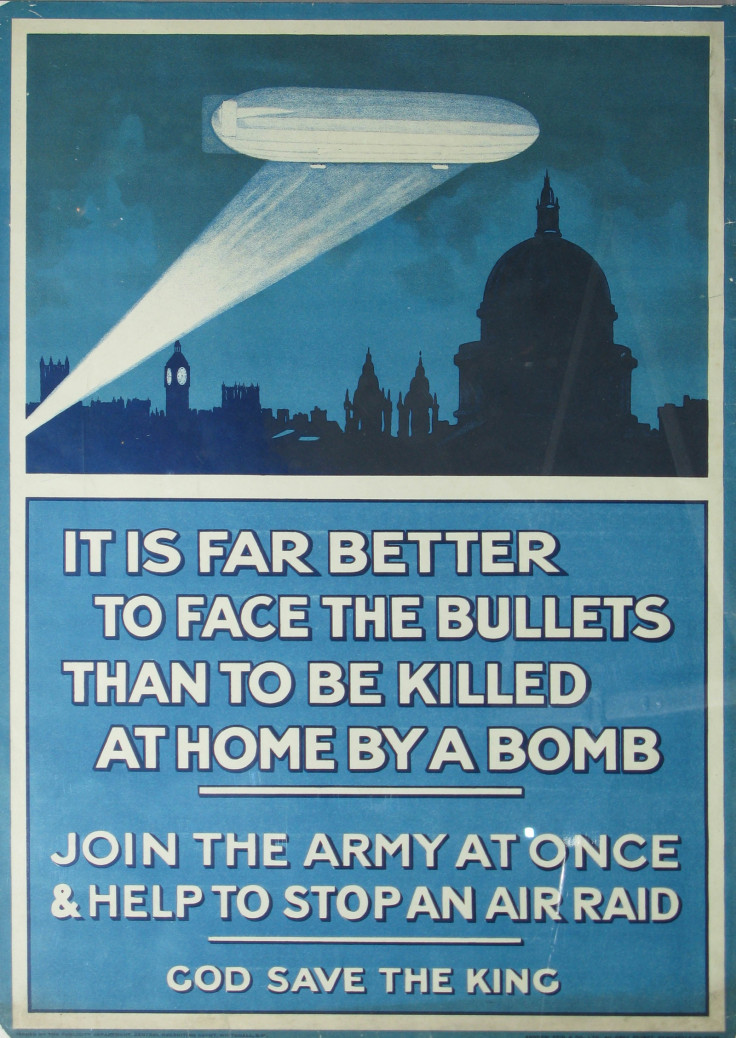

What The Times seemed to be suggesting - perhaps under the influence of the government and secret service - is the concept of "Blitz spirit". That because of the raids, the population would be more likely to increase its efforts against the Germans, particularly by signing up to fight.

In a similar vein, the Daily Mirror front page carried the headline "Every German bomb means another British battalion! The air-huns' recruiting work on the east coast."

Despite the historic significance of the first Zeppelin raids, Holman said the response "actually seems surprisingly subdued, especially when compared with the outrage over the shelling of Hartlepool and Scarborough by German battlecruisers a month earlier".

"This might be because the casualties were relatively small, especially when compared with the prewar expectations," he said.

"But the raid was certainly added to the list of war crimes committed by the German government prepared by the press and other propagandists, lending credence to charges of 'baby-killing' and barbarism.

"Interestingly, though, apart from a few recruiting posters the British government didn't really try to use the first air raids for propaganda purposes to any great extent.

"In fact it asked the press to tone down its reports, first to downplay any suggestion of panic and later preventing the publication of any details which might let the Germans know how effective their bombing was or even where they had been."

Total war

What happened on 19 January was the first of hundreds of air raids on Britain during the First World War by both Zeppelins and planes. Many of them were on the east of England and London because they were closer in range of the bombers.

According to The Western Front Association, there were 4,822 casualties from air raids on Britain during the First World War, including 1,413 deaths.

The Zeppelin missions dropped over 2,700 bombs on towns and cities across the country. The rest were flown by Gotha aircraft, primitive long-range bomber planes.

As for the crews of the two Zeppelins that attacked Norfolk on 19 January, they were awarded Iron Crosses for their grim work. Just a month after the attack, however, they all died after both ships crashed during a snowstorm near Jutland.

"The first air raids confirmed that the British people were no longer protected by the sea, that the air could now be used to attack them," Holman said.

"From one point of view this was just bringing them into line with other Europeans, who had always had to live with the possibility of invasion. But from another it was a harbinger of the era of total war, in which civilians became military targets in and of themselves.

"So people in Britain now began to realise that they were fighting on a 'home front' at the same time as their soldiers were fighting on the 'battle front', and that how they behaved could make a contribution to victory, or defeat.

"In a real sense the Blitz spirit was born not in the Second World War but the First."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.