The history of Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany told in a novel way

The Third Reich in 100 objects, from the swastika and Nazi salute to a Hitler action figure and the Fuehrer's personal moustache brush.

A new book by historian Roger Moorhouse takes a novel approach to telling the story of Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1930s and the dictatorship that followed. He has chosen 100 objects, each representing a different aspect of life in the Third Reich. When put together, these items and the stories behind them provide a broad approach to the complex history of the period.

The objects range from extraordinary historical artefacts to mundane household items. From the swastika flags and stiff-armed salutes still used by fascists around the world today, to the Star of David badges, 'striped pyjamas' and gas canisters used to classify, persecute and kill millions of Jews. The book also features quirkier items such as a Hitler action figure for children, Eva Braun's lipstick case and the Fuehrer's personal moustache grooming kit. Each object is accompanied by an essay providing both vital historical context and fascinating bits of trivia.

IBTimes UK presents 15 of the 100 objects, together with edited extracts from the book.

Object 1: Hitler's moustache brush

This 7 cm horn-backed 'moustache brush' was Hitler's own and was taken from the bedroom of his Munich apartment after his death, by his housekeeper Anni Winter. According to the recollections of Hitler's entourage, it was an integral part of Hitler's toiletry bag, which travelled with him wherever he went.

It is not clear precisely when Hitler adopted the toothbrush style moustache that would become his trademark. During World War I, he sported a fuller 'Kaiserstyle' moustache', so the change must have come after the end of the war. Hitler was extremely image-conscious and worked hard, with his photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, to hone his public image in the 1920s, to create a 'look' that would appeal to his audience. It may well be, then, that his choice of moustache was a part of that process.

Hitler's distinctive look was a key visual element to the success of the Nazis. Just as the swastika has come to symbolise fascism, all you need to represent Hitler is a neat black moustache and limp forelock.

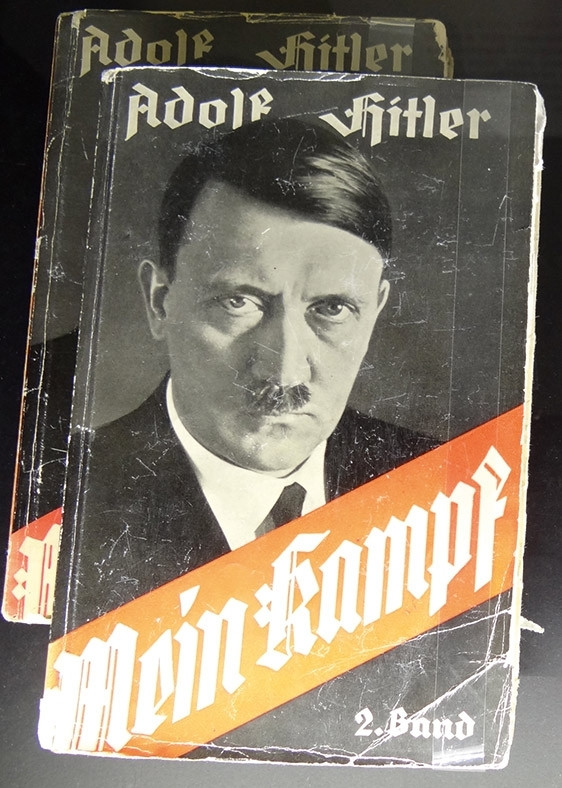

Object 2: A copy of Mein Kampf

Part Nazi manifesto, part rose-tinted autobiography, Mein Kampf expounded Hitler's theories on race, anti-Semitism, anti-capitalism, anti-Bolshevism and current affairs. It was verbose, pretentious and overblown, reflecting the author's intellectual insecurities as much as his prejudices. It was the work of someone so desperate to be taken seriously that he appeared to cram every argument, every supporting piece of evidence, every clumsy metaphor possible, into his text, in the hope that by sheer weight of words alone he would convince his reader.

Review after review criticised the book, attacking not only its content and its glutinous style, but even questioning the mental stability of its author.

Sales were initially sluggish, but as Hitler rose to power and won over the hearts and minds of the nation, the book flew off the shelves. In total, Mein Kampf would sell a remarkable 12,450,000 copies over its author's lifetime. Nonetheless, it is doubtful that many of Hitler's readers – now or during the Third Reich – ever actually read much of Mein Kampf .

Object 3: The Hitler greeting

The use of 'Heil Hitler' with the right arm outstretched, was one of the most iconic and ubiquitous features of everyday life during the Third Reich. The origins of the salute are widely thought to be Roman, and it came to prominence through its adoption by Mussolini's Fascists in the early 1920s, from whom the practice was borrowed by the Nazis.

After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the 'German Greeting' was gradually rolled out to encompass ever larger sectors of German society. In July of that year, all state employees were ordered to use it, and it was stipulated to be used by all those present during the playing of the German national anthem and the Horst Wessel Song.

The use of the 'German Greeting' became a test, a public show of loyalty to the Nazi regime – like displaying a copy of Mein Kampf , or a photograph of Hitler – which many Germans dared not fail, whatever their political convictions. Hitler himself used the greeting only intermittently. In most situations he acknowledged it simply by raising his right hand with the elbow bent and the palm facing forwards.

Object 4: The Hitler Youth uniform

First established as the Nazi Jugendbund or 'Youth League' in 1922, it was originally viewed as a scheme to train boys for a future role in the Brownshirts. The uniform combined the brown shirt and swastika of the Nazi militia with the scouting movement's neckerchief and woggle.

In 1933, with the Nazis in power, the Hitler Youth was finally granted state recognition. Soon all other German youth organisations – from rowing clubs to poetry circles, Boy Scouts to football teams – were forcibly absorbed into the Hitler Youth, boosting membership. By 1939, over seven million young people had joined its ranks.

When war broke out, the Hitler Youth was deployed as an auxiliary force on the home front, helping the postal and fire services as well as assisting anti-aircraft crews. When the German Army faced a crisis in manpower in 1943, Hitler Youth cadres were directly recruited, forming the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend , comprised of 17 and 18-year-olds.

And in 1945, as Germany was invaded from the east and west, youths as young as twelve were enlisted and instructed in how to use the Panzerfaust recoilless gun against enemy tanks. They remained among the most fanatical of Nazis even as the Third Reich crumbled, and many of them would die fighting in a war already long lost.

Object 5: The Autobahn

The German motorway system – or Autobahn – was not a Nazi invention; Italy under Mussolini had the Autostrada from 1925. However, with Hitler's appointment as Chancellor in 1933, motorway-building met with the approval of central government.

The Autobahn project was a classic piece of Keynesianism: the state intervening with a large-scale, labour-intensive, public works programme, thereby providing employment and stimulating a stalled economy. The strategic advantages also seemed obvious. Hitler's planners suggested that by the end of the project, 300,000 German troops could be transported from one side of the Reich to the other in just two days of driving.

Hitler's Autobahn was a propaganda triumph, exploited by the Nazi regime to propagate the image of the Third Reich as a technologically advanced, forward-looking state, with economic centres linked by high speed roads.

By the outbreak of war in 1939, over 3,000 km had been completed. However, the expected strategic advantage also failed to materialise, as for much of the war, the fighting took place far from Germany's frontiers, and most supplies and troops were still moved more easily around the country by train.

Object 6: Heinrich Hoffmann's Leica camera

This rather unassuming looking camera – a Leica IIIa from 1935 – sparked something of a revolution. In the early 1930s most professional photographers were still using plate cameras, cumbersome contraptions on wood and brass tripods. The Leica changed all that. Using 35-mm camera film instead of glass plates, adding a rangefinder for sharper focusing and benefiting from the development of colour film, the Leica was easily portable, robust and reliable. Effectively the first 'point and shoot' camera, it revolutionised photography and even made a new career possible, that of the photojournalist.

Heinrich Hoffmann, a Munich photographer who had helped Hitler to develop his image through the 1920s, acquired a Leica in 1935 and used it to capture some of the most seminal moments of Hitler's odious career, many of which were published in hugely successful picture books, such as 'Hitler in His Home' (1938), and 'The Face of the Führer ' (1939). Hoffman's images were essential components of the Nazi propaganda campaign. Reproduced in countless newspapers, magazines and postcards, they were the images that Hitler's regime showed to the world.

Hoffmann survived the war and died in Munich in 1957. His camera, looted by Allied soldiers in 1945, resurfaced in France in the 1980s.

Object 7: The swastika flag

The swastika – or Hakenkreuz ('hooked cross') in German – was common throughout the ancient world and was most closely associated with India, where it is sacred to the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist faiths. Around the start of the 20th century, mystically-minded German nationalists – most notably the Thule Society – began to claim the swastika as a symbol of the Aryan race, a group they believed to have migrated to Europe from India in prehistory to become the forefathers of the Nordic and Germanic people. It was most probably in this context that the swastika would have first come to the attention of Adolf Hitler.

In the early days of the Nazi Party, Hitler was keen to match the impact of his political opponents' flags. He knew that the Nazis needed a distinctive visual identity. According to his later account, Hitler set about designing his own flag. He copied the red of the Communists and also took inspiration from the old red, white and black Imperial German flag, and incorporated the swastika. A dentist named Friedrich Krohn has also been credited with making a major contribution to the design, having submitted a design which was 'very similar' to Hitler's own.

By the time it was adopted as the national flag in 1935, the swastika had come to dominate the Third Reich. Thereafter, it would become Nazi Germany's face to the world.

Object 8: Arbeit Macht Frei gates

Of all the slogans employed by the Nazis, the common inscription on the gates of the concentration camps was perhaps the most infamous. First used at Dachau in 1936, it would also be used on the entrance gates at Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen and to the ghetto at Theresienstadt.

'Arbeit macht Frei' – or 'Work sets you free' put a positive propaganda gloss on the concentration camps, portraying them as instruments of mass re-education, where – redeemed by their labour – prisoners might ultimately become fit to rejoin the 'national community'. Consequently hard labour became an essential component of concentration camp life, with prisoners providing labour to the SS and to German businesses large and small, from huge industrial concerns to local butchers and bakers.

Of course the idea that a concentration camp inmate might find 'liberation' through his or her labour was utterly fanciful. Prisoners were often released from the camps – before the outbreak of war at least – but the decision was entirely on the whim of the SS or Gestapo, and thus entirely independent of the amount, or the quality, of an inmate's work. 'Arbeit macht Frei', therefore, was nothing but a cynical, empty promise.

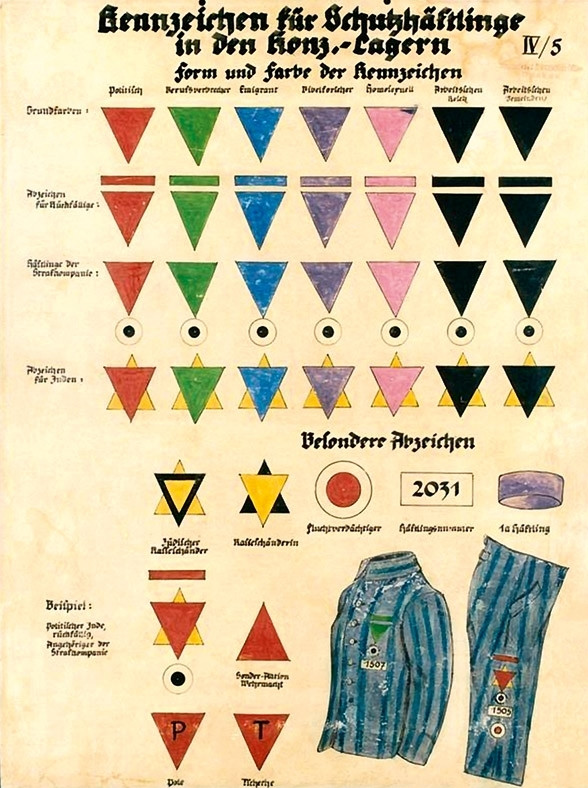

Object 9: Concentration camp badges

A system of coloured badges that allowed SS guards to visually ascertain a prisoner's status and background was introduced at the concentration camps in 1936. Sewn on to their prison uniform under their prison number, the colour of the triangle denoted the nominal reason for the prisoner's incarceration – red for political offenders, green for habitual criminals, blue for 'emigrants' (those who had been expelled from Germany and had returned), purple for Jehovah's Witnesses, pink for homosexuals and black for 'asocials'. Those prisoners who were Jewish had an inverted yellow triangle added to their designation, thereby forming a Star of David.

Bars and circles could be added to denote repeat offenders, would-be escapers and those on punishment details. After 1939, initials would also be used to denote nationality: F for French, B for Belgians, P for Poles, T for Czechs (Tschechen in German) and so on.

Political prisoners made up the largest single category, in large part because it served as a catch-all for most opposition activity. However, particular camps could have a larger proportion of a particular category at certain times: Sachsenhausen, outside Berlin, held a larger proportion of homosexual prisoners than most other camps.

The system could dictate how a prisoner was treated, and thereby decide their fate. Jewish prisoners could always expect harsh treatment from the guards, but 'politicals' were also prone to random persecution, as were homosexuals and repeat offenders, who were much more likely to be consigned to a punishment detail, with predictable results. At Dachau, for instance, the death rate among homosexual prisoners was consistently higher than for heterosexuals.

Those with green triangles, meanwhile – criminals – were often favoured by the camp authorities to serve as Kapos; the trusty prisoners who took charge of each barrack block, in return for improved conditions. The fact that they were merely 'criminal' and not 'political' or 'asocial', evidently elevated them in the eyes of some of their SS overlords.

Object 10: Hitler action figure

Like any regime with totalitarian ambitions, the Third Reich sought to bring Germany's children under its nefarious influence as early as was possible. In the battle for young hearts and minds, toys were a useful weapon, particularly those with a military or political theme – such as this Hitler figure. They were

highly sought-after by German children during the Nazi period.

The Ludwigsburg firm O&M Hausser produced a selection of Hitler figures, featuring him seated, standing or speaking at a podium hung with a swastika. Some of them had a hand-painted porcelain head; others – as in this example – even had a movable right arm, so that he could be made to salute.

They were part of a huge range of figures which included Mussolini, Hermann Göring and Francisco Franco. More elaborate models included artillery guns that fired a small projectile and rifles that released a puff of smoke.They would originally have sold for around five Reichsmarks each, and with the average weekly wage in 1938 at around 30 Reichsmarks, they were certainly not cheap.

Ironically, the sale of the figures was halted in 1943, when the shift to a 'total war' economy in Germany put an end to almost all non-military production. By that time, of course, many of those Germans who had been raised playing with toy soldiers in the 1930s were already fighting for real on the battlefields of Europe.

Object 11: The Volkswagen Beetle

Hitler recognised the political and propaganda potential of a small, affordable, car, and announced his intention to motorise the German nation at the Berlin Motor Show in 1933. He gave designer Ferdinand Porsche the task of developing a car that could transport two adults and three children at 100 kmh, with fuel economy of no less than 32 miles per gallon, and all for the price of 990 Reichsmarks – a fraction of the cost of other models. For the first time, it seemed, motoring was within the reach of the ordinary man and woman.

The Kraft durch Freude-Wagen ('Strength through Joy Car') – abbreviated to KdF-Wagen – was an air-cooled, rear-engine car with the characteristic, aerodynamically efficient 'beetle' shape. Huge sums of money were pumped into the project and the first prototypes – the Type 60 – were produced in the autumn of 1935.

About 300,000 German consumers dutifully signed up for their new cars, purchasing 'stamps', at a value of 5 Reichsmarks each, which would be stuck into a savings book and would count towards the cost of the car. Buyers were to be disappointed, however. Though the final prototypes were completed in 1938, they were presented to Nazi dignitaries rather than ordinary customers; Adolf Hitler himself received one on his fiftieth birthday in April 1939.

Then, with the outbreak of war later that year, production at Wolfsburg was switched to making military vehicles such as VW's military variant, the Kübelwagen, and the amphibious Schwimmwagen. No KdF-Wagens were ever presented to ordinary subscribers by the Nazi regime, despite the fact that 278 million Reichsmarks had been paid into the scheme.

In 1945, the Wolfsburg factory was taken over by the British occupation authorities, and production was restarted to provide work as well as a few hundred vehicles for use by the occupying forces. Production swiftly grew, and by March 1946, the factory was producing 1,000 cars per month. Rebadged as the iconic 'Volkswagen Type 1', the KdF-Wagen successfully shed its Nazi past and became a symbol of Germany's post-war economic rebirth.

Object 12: Mercedes-Benz 57 770 Limousine

Hitler was a keen fan of cars, particularly those of Mercedes-Benz. He was an avid reader of car specifications and kept up to date with the latest developments. He even said he had sent sketches to Mercedes-Benz, and thereby claimed 'fatherhood' for some of the marque's later designs. In total, Hitler's Chancellery would order over sixty cars from Mercedes-Benz.

The most remarkable was the 770KW150, the first of which was delivered to Hitler in April 1939. Its addition features included 40 mm bulletproof glass all round, 18 mm steel doors, run-flat tyres and a 10 mm steel reinforced floor; all of these were designed to make the car impervious to attack with handguns and with up to half a kilogram of explosives. All that extra steel and glass made the car hugely heavy, of course, pushing its kerb weight up to 5 tons and giving horrific fuel economy figures of barely 6 miles per gallon.

However, for all the ingenuity of Hitler's security regime, it is doubtful how far such measures might have protected him in the event of a serious attack. After all, Hitler's his habit was to stand in the passenger footwell – in plain view – to receive the adulation of the crowd. In such circumstances, a determined assassin armed with a pistol or a hand-grenade would have been untroubled by the car's bullet-proof windscreen and armoured doors. Hitler evidently

considered being safe was of secondary importance to being seen.

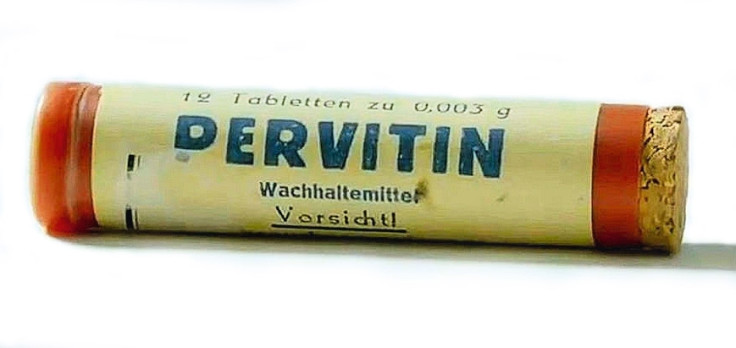

Object 13: Pervitin

Pervitin was an early, low-dose version of what would now be called crystal meth, or methamphetamine hydrochloride. Inspired by the American use of Benzedrine during the Berlin Olympics of 1936, Pervitin was developed by the pharmaceutical company Temmler and first introduced onto the German market in 1938, in tablet form. Marketed as a stimulant, an 'alertness aid' to ease symptoms of everything from depression to lack of libido, it quickly proved popular with the civilian population.

Inevitably, its popularity brought the drug to the attention of the German military, and by the summer of 1939 Dr Otto Ranke of the Berlin Academy for Military Medicine was carrying out experiments to assess its effectiveness on military subjects. He noted that the drug's effects were similar to those of adrenaline: a heightened state of alertness, increased self-confidence, reduced inhibitions and a greater willingness to take risks.

It was easy to conclude that Pervitin would help Germany win the war. So, in the spring and summer of 1940, more than 35 million Pervitin tablets – known colloquially as 'Stuka-tablets' – were distributed to the German military. Users were advised to take one or two 3-milligram tablets, as required, to 'maintain sleeplessness'.

Pervitin's spell didn't last, however. Though its initial benefits to men in combat were self-evident, Wehrmacht doctors became increasingly concerned about the drug's side-effects, the growing resistance evident amongst users, and of course the high incidence of addiction. Some soldiers are reported to have turned violent, committing war crimes against civilians or attacking their own officers. So in 1940 the army seriously cut back its usage of Pervitin.

Object 14: Zyklon-B canister

Hydrogen cyanide was originally developed in the late nineteenth century for use as a pesticide. Given that the Nazis viewed their racial enemies as little more than vermin, it is brutally logical that Zyklon-B would, in time, also be used for the killing of human beings. The first experimental instance of killing using Zyklon-B was in early September 1941 in the main camp at Auschwitz.

The process of killing with Zyklon-B was refined until it was simple and relatively swift. Victims would be ordered to strip before entering a gas chamber, often disguised as a shower block, with a gas-proof door sealed behind them. Then, Zyklon-B pellets would be dropped from a canister through a hatch in the roof or the wall. With exposure to heat and moisture, the pellets would quickly degrade and give off hydrogen cyanide gas. For those victims closest to the pellets, death would occur within minutes; those further away took longer to succumb

In all, around one million people were murdered by the Germans using Zyklon-B, mostly at Auschwitz II-Birkenau. That camp alone would consume over 24 tons of Zyklon-B between 1942 and 1945.

Ironically, the inventor of Zyklon-B, Walter Heerdt, was an opponent of the Nazis, who was removed from all positions of influence in 1942. His rival, the chemical's distributor Bruno Tesch, was less circumspect. Tried as a war criminal in 1946, Tesch would claim that he had been unaware of the murderous purpose to which his deliveries had been put – but his defence was fatally undermined when it was shown that he had visited Auschwitz to brief SS guards on Zyklon-B's use. Tesch was hanged in Hamelin Prison in May 1946.

Object 15: Göring's cyanide capsule

Suicide was widespread in 1945, as a generation of Germans were forced to confront the harsh realities of the collapse of Nazi Germany and the prospect of justice or vicious reprisals at the hands of their enemies. It was a course of action that even had the official sanction of the Nazi regime. Over 3,000 cyanide vials, complete with brass containers made from spent rifle cartridges, were made by the SS, using laboratories in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Each one contained a cubic centimetre of hydrocyanic acid, enough to kill an adult within a couple of minutes.

Around 1,000 of them were delivered to the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, for distribution to the Nazi elite. Hitler and Goebbels killed themselves in the Berlin bunker, and Himmler took cyanide in Lüneburg after he fell into British hands in May 1945. At least a hundred other top Nazis committed suicide.

Hermann Göring broke this glass vial of cyanide between his teeth in his prison cell on the night of 15 October 1946. The Nuremberg Tribunal had sentenced him to death two weeks earlier, having been found guilty on all four counts of crimes against peace, planning wars of aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity. His guilt, the judgment stated, 'was unique in its enormity'.

It is still unclear precisely how he came into possession of the cyanide capsule; some accounts maintain that he smuggled it into the cell himself and concealed it for a year; others suggest that a prison guard, Lieutenant Jack Wheelis, was charmed and bribed by Göring to deliver the poison to him unwittingly. Another account states that Obergruppenführer Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski – who was at Nuremberg as a prosecution witness – managed to hand the cyanide capsule to Göring personally, concealed in a bar of soap.

If you'd like to read more about these 15 objects, plus another 85, order The Third Reich in 100 Objects by Roger Moorhouse, published by Pen & Sword Books.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.