30,000 excess deaths linked to NHS and social care cuts

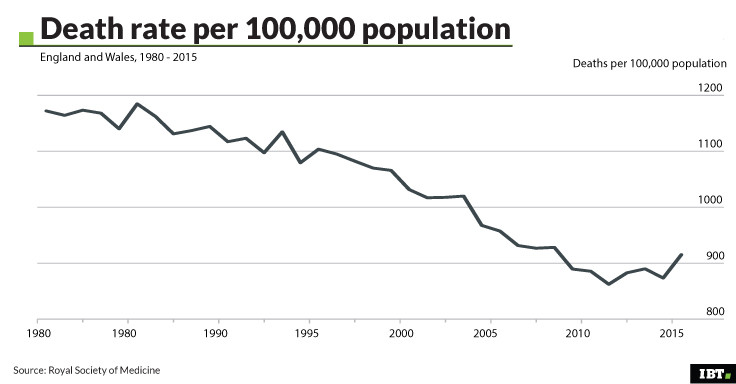

Death rates in 2015 were higher than previous years, with a larger than usual spike in January.

Underfunding of the NHS and social care services in England and Wales have been linked to the highest annual excess death rates in 2015 since the Second World War in two new studies.

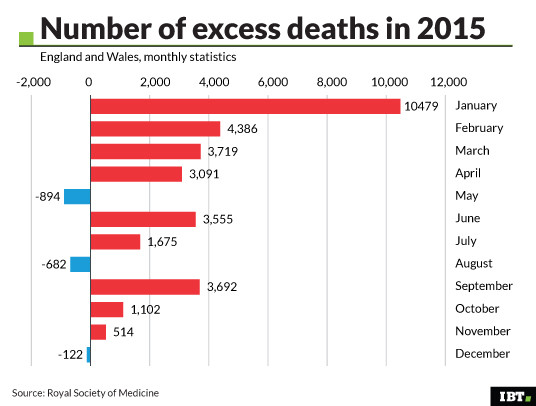

The pair of papers published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine find that there were 30,000 more deaths overall in 2015 compared to 2014, and that the winter spike in deaths in January 2015 was much larger than usual. Overall, death rates of older people were up to 12% higher in 2015 than in 2014, the study found.

The spike in deaths in January – which happens most years, associated with cold weather – was much larger than usual, they found. The total number of weekly deaths in the second to fifth weeks of 2015 were well above the five-year average for that time of year.

The UK's ageing population is likely to have contributed in part to higher death rates. There are increasingly more elderly people, which leads to gradually increasing death rates. However, this factor alone cannot account for the sudden spike in deaths in 2015.

The authors also looked at the death rates of individual yearly ages where the data was available, to calculate the death rates for people of each age and how they changed in 2015. This allowed comparison between, for example, the death rate of 70 year olds in 2014 and those in 2015.

Bad case of flu?

This heightened death rate in the 2014/15 winter has been noted before. An Office for National Statistics report published in November 2015 said that high levels of influenza, particularly of strains that most affect the elderly, were thought to be behind the heightened death rate for the year.

The new pair of studies finds that cases of flu were not particularly high in the UK or the rest of Europe that winter, however the flu vaccine that year was not very effective. This may also have made a slight contribution to the spike. Other common causes of higher mortality rates such as very cold weather were ruled out as it was a mostly mild winter in the UK.

"The baseline death rate is shifting up compared with much of the rest of Europe and the spike in January in particular is getting massively exaggerated in a particularly warm winter, when flu moving around Europe was not very high," study author Danny Dorling, a social geographer at the University of Oxford, told IBTimes UK.

Martin Mckee, professor of European public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, also an author of the study, said that the increase was "very remarkable" as one of the largest increases in deaths in the UK since the Second World War.

"The two other comparable increases were global flu pandemics. There was no flu pandemic in 2015. We know we're looking at something that's exceptional," McKee said.

"When you've eliminated other causes, what's left is the most likely. Although we can't say exactly what was happening, we can say there is a very strong argument for looking in detail at what's happening."

Strains on services

After ruling out bad weather and disease epidemics, the authors draw a link between the increased death rates and cuts to health and social care budgets in the 2010-15 period. The majority of the excess deaths were in older people with Alzheimer's or dementia, who are particularly reliant on health and social care services.

"These are people who are frail and weak. When care becomes worse, it's that group who dies first," said Dorling.

The study focused on NHS 111 calls, ambulance dispatches, admissions to A&E departments and A&E waiting times. They found lowered marks of performance, such as greatly increased numbers of patients waiting more than 12 hours in A&E. Although no direct causal links can be drawn from this data, the authors say it calls for more research into the cause of the heightened death rates.

"If you don't look at these patterns, you may become used to a much poorer quality of care and falls in life expectancy. This is what we appear to be moving," said Dorling.

'Arithmetically impossible'

The Department of Health disputed the claims made in the studies and rejected the suggestion of a link between strained health and care services and increased mortality.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health said: "This report is a triumph of personal bias over research – for two reasons. Every year there is significant variation in reported excess deaths, and in the year following this study they fell by nearly 20,000, undermining any link between pressure on the NHS and the number of deaths."

However, these figures use mid-year to mid-year calculations rather than calendar year calculations in the two new studies.

"In our new papers we look at calendar year to calendar rises, which were less dramatic and from which there has not been such a fall," said Dorling. "Maybe one reason the situation is now so bad in terms of deaths in England is because people in the Department of Health do not understand these numbers."

The Department of Health spokesperson said that there had been an overall increase in the NHS budget of almost £15bn ($18.7bn) between 2009-10 and 2014-15, so a link between health and social care cuts and increased mortality was "arithmetically impossible".

They added that from April NHS trusts would "be asked to review potentially avoidable deaths in order to learn and improve the safety of care". A Scottish government spokesperson said that it would be looking into the analysis, although it did not include data on the Scottish population.

Where to look next

Peter Goldblatt, a senior advisor at UCL's Institute of Health Equity and former Chief Medical Statistician at the Office for National Statistics who was not involved in the research, said that the study was "well done and the conclusions were fairly balanced". The studies do not draw a clear causal link between underfunding of health and social care and increased mortality.

"They are saying that none of the usual explanations provide the whole picture, and that's why you need to look at the kind of factors to which the elderly are most sensitive," said Goldblatt. "Health and social care are key factors in the circumstances."

However, he cautioned that the UK's ageing population may play a bigger role in the figures than is accounted for. He said there was a need for further research into how this adds pressure on health and care services.

The first problem to consider was the direct impact of inadequate social care on the functioning of the NHS. "Essentially the failure to get people who are medically fit out of hospital with care packages. There's a lack of beds in the NHS so that does block the system, which feeds back into A&E and ambulance response times."

Pressure on care homes is the second major factor, Goldblatt said. "Again, there's a lot of evidence here that many of these deaths were people who had been in care homes. If funding for care is being reduced there are more pressures on care homes, then again perhaps people aren't getting the attention they need."

System-wide search

In addition to further academic research on the potential link between health and social care cuts and mortality, McKee called for the Chief Medical Officers of the UK to address the spike in deaths.

"As far as I know they have said nothing about this. In whose remit is it to look at the care and social system as a whole and ask, have we reached a point where inadequacies are resulting in us having life expectancy no longer rising for older people?"

The Chief Medical Officer for England, Sally Davies, was said not to be able to comment as it was outside her area of expertise. The Chief Medical Officer for Wales did not respond to a request for comment.

"When individual hospitals go wrong, you get an investigation in a particular hospital," said McKee. "When the system as a whole goes wrong because it's underfunded, there isn't anyone who does an investigation in the whole system."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.