400-year-old bones solve mystery of what the dodo really looked like

16th and 17th century sailors differed wildly in their descriptions of the dodo's appearance.

The life cycle of the dodo has been unveiled from analysis of 22 bones from the long-extinct flightless bird. The findings could explain a long-standing mystery of why there were so many contradictory descriptions of the bird's appearance.

For a dodo, life really kicked off in August. This was when female birds ovulated, becoming fertile and interested in mating. They then laid their eggs around September and incubated them for several weeks. Tiny dodo hatchlings would have appeared around the end of September.

After that, a race against time began for the baby birds to grow large and strong enough to withstand the harshest months in Mauritius – the austral summer, between November and March. This period was filled with vicious storms that would have made foraging and survival particularly hard for the dodo.

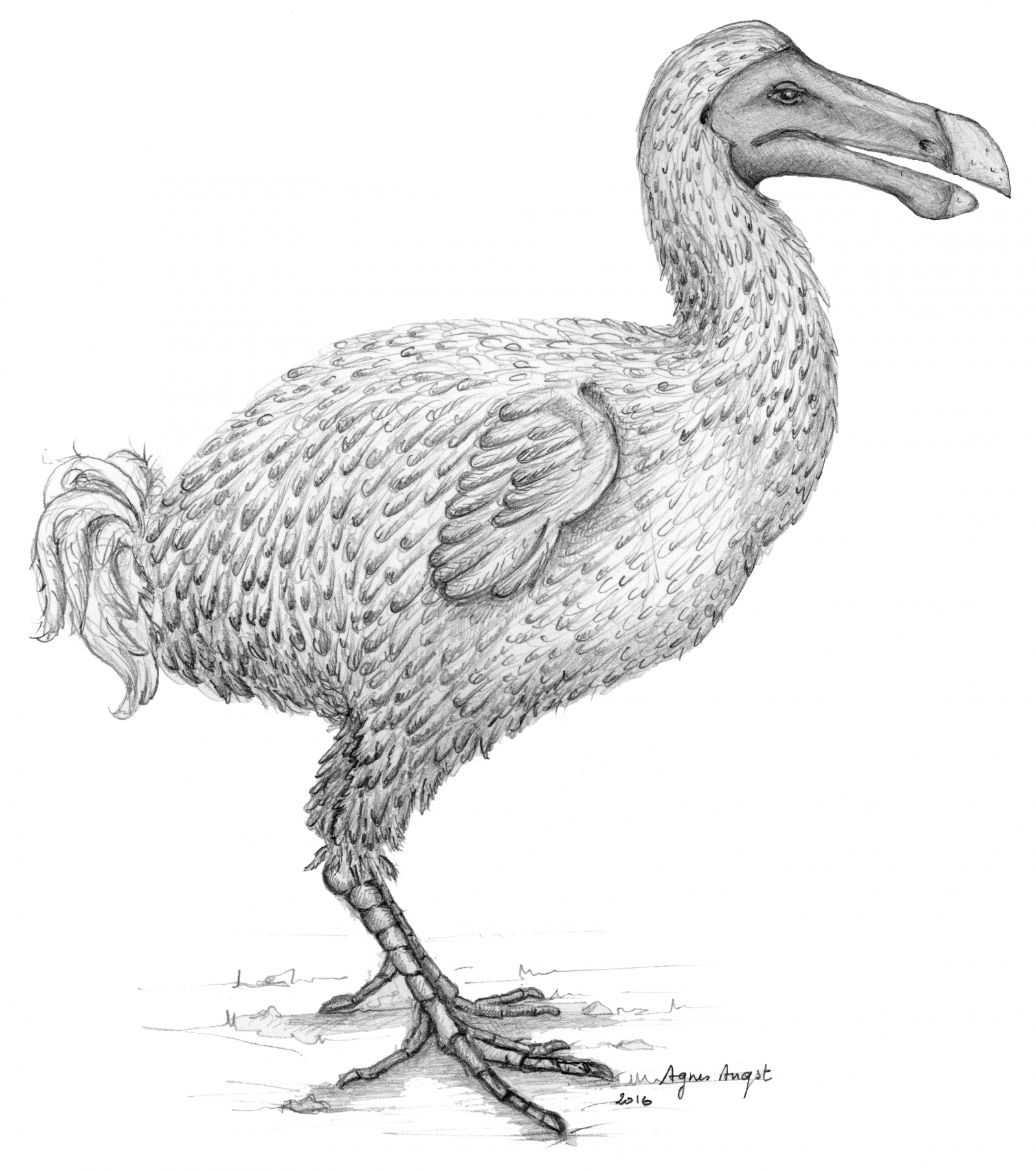

Once the stressful summer was over, the birds would begin to begin to moult, leaving them clad in only a downy layer. It would take them several months to slowly regrow their plumage, one part at a time, until they would be fully covered in fresh feathers by about July.

How could researchers have built such a detailed picture of the bird's lifecycle from just 22 bones of the animals which have been extinct since the 17th century? It's all down to the calcium deposited in the bones, researcher Delphine Angst of the University of Cape Town, South Africa, told IBTimes UK. A study by Angst on the bird bones is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

"When female birds ovulate at the beginning of the breeding period, they produce an extra amount of bone. This is because they have to have a big reservoir of calcium for forming eggshells," Angst said.

Moulting, too, leaves its marks in the bones of the birds. Regrowing feathers also takes a large quantity of calcium. It can lead to large holes appearing in the bone, which Angst and her colleagues also observed in their samples. These marks were then aligned with an annual event that left a regular signature in the bone.

"We observed lines of arrested growth on the external part of the bone. These correspond to a moment when the adults temporarily stopped growing. That's linked to very, very bad environmental conditions," Angst said.

This was the yearly marker of the austral summer. By seeing how much bone had been laid down after this line of arrested growth, the team could work out when the events of ovulation and moulting fit into the dodo's calendar.

As well as painting an unprecedented and detailed picture of the dodo's life cycle, the research sheds light on a puzzle in the historical accounts of the dodo. They were recorded primarily by mariners between their discovery in 1598 by Dutch sailors and the species' demise in the second half of the 17th century. They all described a large trusting flightless bird, but no one could agree on its plumage.

"What we can read in the old documents written by the sailors was some descriptions of dodos with a downy, fluffy, dark plumage. Other descriptions were of dodos with a mixture of downy feathers and real feathers. Others described dodos with only real feathers," said Angst.

Scientists frequently dismissed these descriptions, saying that the sailors had no scientific training and might not be accurately describing the bird's appearance at all. But Angst and her team's research shows that the sailors were right all along.

"The description of the downy feathers corresponds to a month at the beginning of moulting. A little later we have a description of mixed feathers. This makes sense too because when birds regrow their feathers it doesn't all happen at once. And descriptions of dodos from July talk about a dodo with completely normal feathers," said Angst.

When the dates of the descriptions were aligned with the newly discovered calendar for dodo moulting, the descriptions matched up perfectly. The sailors were actually recording the dodo's perfectly normal annual moulting.

"That's why they're such cool birds," Angst concluded.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.