British Museum's 9,500-year-old Jericho skull was a man with rotting teeth and a broken nose

A micro CT scan has shed light on the bones and face of the man hiding behind the plastered skull.

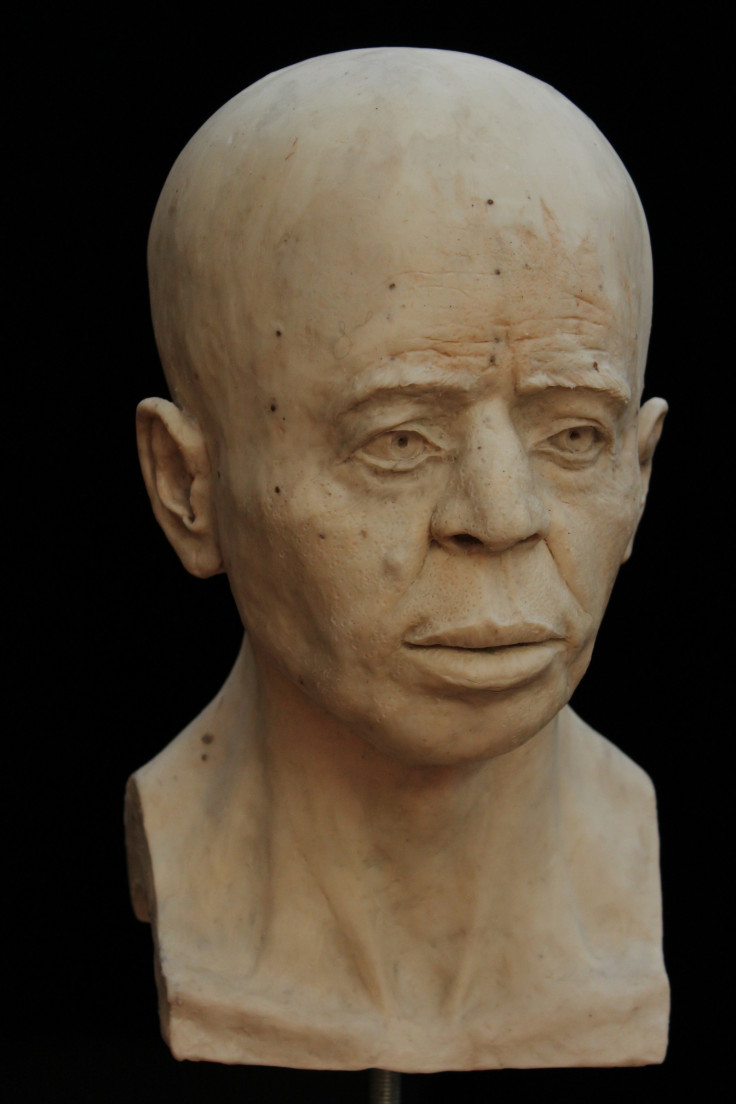

The Jericho skull is among the oldest human remains in the British Museum Collection, and for the first time, scientists have successfully reconstructed the face that this person would have had. In-depth research also indicates that this was a man who was older than 40 years old when he died.

The skull is one of seven unearthed together by archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during excavations in 1953, at Jericho in the Palestinian territories. The skull, now located at the British Museum, is believed to be between 8,500 and 9,500 years old. It is actually a cranium, because the lower jaw has been removed. Like the other seven skulls, it had been decorated and covered with plaster.

For archaeologists, this is an intriguing practice, but it remains a little puzzling. Plastered skulls are believed to have been an important part of Neolithic rites to honour the dead, but it is not known what purpose the tradition served. A hypothesis is that the skulls that went through this process might have belonged to elder males or revered members of the community.

In the case of the Jericho skull, the practice had so far prevented archaeologists from learning more about who the person was, since most of the bones were hidden under the plaster.

Decayed teeth, broken nose

However, recent work using a micro CT scan of the plastered skull has enabled real progress to take place. It has revealed new clues about the individual's identity and has allowed experts from the Imagining and Analysis Centre at the Natural History Museum to reconstruct a model of the skull and the face.

"The point of this work and of our exhibition is to engage better with the British Museum's audience. We want to show that the skull belonged to a modern human that looks a lot like us, even if he lived more than 9,000 years ago, we want to close that gap in time", Dr. Alexandra Fletcher, the curator for the Ancient Near East, told IBTimes UK.

Images from the scan were examined and served as a basis for printing a 3D model of the

bones beneath the plaster. For the first time, researchers were able to take a peak at hidden areas of the Jericho skull, from the cheekbones to the brow and eye sockets.

In-depth analysis of the skull's shape led scientists to conclude that the individual was male, and that he died when he was older than 40. He had broken and decayed teeth. "His dental health wasn't that great and this may relate to the changes in diets that were happening at the time, with the introduction of cereals that may have increased people's sugar intake", Fletcher explains.

There were also signs that his nose had been broken during his life, although it had already healed when he died. Furthermore, there is evidence that the man's head would have been intentionally bound when he was a child, although it is not clear if that was done for aesthetic purposes or if the practice had a deeper meaning.

With all these data, the experts were able to create a facial reconstruction of the man. Details like hair and eye colours are missing, but the researchers are confident that they have reproduced an accurate model of the Jericho skull by using a non-invasive technique, similar to what is used to identify victims in police investigations.

"We are missing some details, and our facial reconstruction may differ a little from what the man may have looked like, but the idea is if he had walked in with this face, family members and friends would have been able to recognise him", Fletcher says.

The reconstructions and the findings from the research can be seen at the British Museum from 15 December 2016 to 19 February 2017.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.