Alastair Campbell interviews Prince William about Diana: 'She smothered Harry and me in love'

"I still feel very angry that we were not old enough to be able to do more to protect her."

"So what's a nice future King like you doing with an old leftie Republican like me?" It seemed like a good enough question to start with. I was, after all, surprised to be there, in Kensington Palace, interviewing Prince William. I had already been similarly surprised by being asked a few weeks earlier to take part in a campaign spearheaded by William, his wife Catherine, and his young brother Harry.

"To be honest," he replied, "I really don't care where people come from. And this is a good opportunity to talk about something that is very close to your heart, and very close to mine."

Having had mental health problems myself, I was asked by The Young Royals to take part in films for their campaign, Heads Together.

So there we were, sipping tea together, and talking about his life and times, and a good deal more than mental health.

As well as testing his commitment to this cause, I wanted to see how close to the public persona the more private man in his own habitat might be. Would he speak with the same stilted style that seems to characterise his public speaking? He didn't. Would he have a sense of humour? He did. Would he stand on ceremony? He didn't. Was there any real passion behind the shy exterior? There was.

There was another connection though, that perhaps tempted him to agree to the interview, which was for GQ magazine, namely that I knew his mother, the unforgettable, unforgettably beautiful, unforgettably sad, unforgettably mischievous Princess Diana.

I had met her several times when I was working for Tony Blair in Opposition in the mid-90s, and as my published diaries record, despite all the things I wrote about her in my Daily Mirror days – alas, she remembered – I was smitten. How on Earth could I not be, when her very first words to Tony Blair were to ask what I was like, and whether we might meet – about as big a boost to the male ego as could be had?

We did so a few hours later when I went to collect TB from their private meeting, and she came out for a chat in the street where we had parked, remarking "wouldn't this be a great picture?"

She often talked about pictures, about the media, about her profile. "They can take everything from you, but they will never take your pictures," she once said to me, not entirely clear who "they" were. But my accounts of these meetings meant William knew he would be talking to someone who shared not only an interest in breaking down the taboos of mental health, but a fondness for his mother, whose death in Paris twenty years ago this week was one of the defining episodes of modern history, and of course of William's life.

Looking back, the outpouring of grief and emotion was very touching but it was very odd to be in that situation.

A fair part of our conversation was about grief – not just the searing emotional pain and his difficulty in coming to terms with it, so that only now does he really feel able to open up about his mother, but also his evident anger at the role of the media, their hounding of her in life and their chasing her to the very end in the tunnel where she met her death; and the torture he went through in walking behind his mother's coffin, things of which I was aware at the time, working then for newly elected Prime Minister Tony Blair in 1997, and seconded to support the Palace team planning the funeral. That, for a Republican, was an experience even more bizarre than sitting talking to the future King.

"It was one of the hardest things I have ever done," he admitted of that long walk behind the coffin, alongside his brother Harry, his father Prince Charles, his grandfather Prince Philip, and his uncle, Diana's brother, Charles Spencer. "But if I had been in floods of tears the entire way round how would that have looked?" That is easily said, and of course the 'stiff upper lip' is very much part of upper class British thinking. But, I asked, as a teenager mourning your mother, whom you clearly loved so much, "how can you not be in floods of tears if you feel like being in floods of tears?"

"In the situation I was in, it was self-preservation," he replies. "I didn't feel comfortable anyway, having that massive outpouring of emotion around me. I am a very private person, and it was not easy. There was a lot of noise, a lot of crying, a lot of wailing, people were throwing stuff, people were fainting. Looking back, the outpouring of grief and emotion was very touching but it was very odd to be in that situation."

Along with most of the senior Royals, he was up at Balmoral Castle in the Highlands of Scotland when tragedy struck. He and Harry had taken a call from Diana a few hours before she went out, for the last time, and both now say they wished they had spoken to her for longer. As the world came to terms with the news, the Queen and Prince Charles decided Balmoral was the best place for the boys to absorb and deal with what had happened, and that they should stay there.

They were hidden away, saw no newspapers, no TV. William says he was totally unaware of the vast outpouring of grief around the world, but especially the extraordinary scenes developing over the days immediately after her death in the Mall, outside Buckingham Palace. "All I cared about was I had lost my Mum. I was fifteen, Harry almost thirteen, and the overwhelming thing was we had lost our mother."

I feel very sad and I still feel very angry that we were not old enough to be able to do more to protect her.

Even when the Royals flew south a few days later, amid a growing sense of rebellion among the public, angry that the Buckingham Palace flag was not being flown at half-mast, the Queen's 'loyal subjects' feeling she and the other Royals were not sharing their pain, he said he couldn't really take in all in.

To my question – "did you grieve?" – there was a long pause, before he said: "Probably not properly. I was in a state of shock for many years. People might find that weird, they might think of shock as something that is there, it hits you, and then in an hour or two, maybe a day or two, you are over it. Not when it is this big a deal, when you lose something so significant in your life, so central, I think the shock lasts for many years."

Living that grief, as with every other part of their lives, in the public gaze, does make it more difficult, he says. "It doesn't make you less human, you're the same person. It is a part of the job to have the interest. The thing is you cannot bring all your baggage everywhere you go. You have to project the strength of the United Kingdom – that sounds ridiculous, but we have to do that. You can't just be carrying baggage and throwing it out there and putting it on display everywhere you go.

"My mother did put herself right out there and that is why people were so touched by her. But I am determined to protect myself and the children and that means preserving something for ourselves. I think I have a more developed sense of self-preservation." That's twice he has used the phrase "self-preservation." It is clearly a mindset.

It partly explains why he does all he can to prevent his own children, George and Charlotte, from being as exposed to the media as he and Harry were in their childhood. "I could not do my job without the stability of the family. Stability at home is so important to me. I want to bring up my children in a happy, stable, secure world and that is so important to both of us as parents. I want George to grow up in a real, living environment, I don't want him growing up behind Palace walls; he has to be out there. The media make it harder but I will fight for them to have a normal life outside these palace walls."

He denies that it was Diana's own issues with bulimia that led him and Harry to adopt mental health as their cause, yet there is no doubt the struggles they have had in dealing with loss have given them an empathy and understanding on mental health that helps to bring it alive for people.

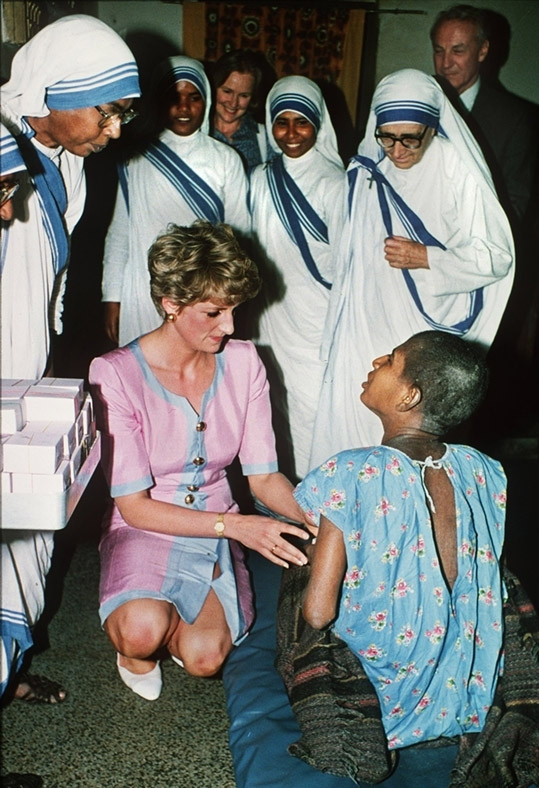

They have continued to maintain contact with a refuge for the homeless she first took them to when William was twelve, and Harry ten. They speak with real pride of the way in which Diana shifted the dial, globally, on issues like Aids, or clearing former war zones of landmines.

He encourages his own staff to be open with him about their mental health, adding: "If I had mental health issues I would happily talk about them. I think the closest I got was the trauma I suffered when I lost my mother, the scale of the grief, and I still haven't necessarily dealt with that grief as well as I could have done over the years. I have always believed in being very open and honest."

Admitting that in his position it is not always easy to know who to trust, he says: "One of the few strengths I might have is that I am good at reading people, and I can usually tell if someone is just being nice because of who I am, and saying stuff for the wrong reasons. I have not talked to a specialist or anyone clinical, but I have friends who are good listeners and on grief, I find talking about my mother, and keeping her memory alive, very important, and I find it therapeutic to talk about her, and to talk about how I feel."

He adds: "I have never felt depressed in the way I understand it, but I have felt incredibly sad. And I feel the trauma of that day has lived with me for twenty years, like a weight, but I would not say that has led me to depression. I still want to get up in the morning, I want to do stuff, I still feel like I can function. Believe me, at times it has felt like it would break me, but I have felt I have learned to manage it and I've talked about it. On the days when it has got bad I have never shied away from talking about it and addressing how I feel. I have gone straight to people around me and said "listen I need to talk about this today."

He gives me an example, arising from his 'day job' as an air ambulance pilot in the East of England. "Last week, I flew to a really bad case, a small boy and a car accident. I have seen quite a lot of car injuries, and you have to deal with what you see but every now and then one gets through the armour. This one penetrated the armour, not just me but the crew who have seen so much. It was the feelings of loss from a parent's point of view, the parents of the boy.

"Anything to do with parent and child, and loss, it is very difficult, it has a big effect on me, it takes me straight back to my emotions back when my mother died, and I did go and talk to people at work about it. I felt so sad. I felt that one family's pain and it took me right back to the experience I had. The more relatable pain is to your own life the harder it is to shake it off."

I tell him of the times I met his mother, in the mid-nineties, and recall when she said to me "why did you used to write those horrible things about me when you were a journalist?" I said "my God, I can't believe you read that stuff." I was shocked that she had read it and also had remembered it. And it made me think at the time that some people reach a certain level of fame that media and public cease to see them as human beings. I ask him if he thinks that is what happened to her, and does he think it has happened to him ever?

"Not with me, no. I think with her it was a unique case. The media issue with my mother was probably the worst any public figure has had to deal with... the complete salacious appetite for anything, anything at all about her, even if there was no truth in it, none whatsoever."

To this day, he can easily express anger at the way the press treated his mother and, given they were often with her, himself and his brother. He recalls her being spat at, sworn at, pushed physically, photographers hoping to get a better picture out of her reaction. Yet surely, I say, there is an argument that she cultivated her own friends in the media and fed the whole thing, particularly at the time her marriage to Prince Charles was disintegrating?

I think she was possibly a bit naïve and ended up playing into the hands of some very bad [media] people.

"I have been exploring this. Remember I was young at the time. I didn't know what was going on. I know some games and shenanigans were played but she was isolated, she was lonely, things within her own life got very difficult and she found it very had to get her side of the story across. I think she was possibly a bit naïve and ended up playing into the hands of some very bad [media] people. This was a young woman with a high profile position, very vulnerable, desperate to protect herself and her children and I feel strongly that there was no responsibility taken by media executives who should have stepped in, and said 'morally - what we are doing, is this right, is this fair, is this moral?'

"Harry and I were so young, and I think if she had lived, then when we were older, we would have played that role, and I feel very sad and I still feel very angry that we were not old enough to be able to do more to protect her, not wise enough to step in and do something that could have made things better for her. I hold a lot of people to account that they did not do what they should have done, out of human decency."

I tell him that during the week of her death Tony Blair spoke to Prince Charles by telephone and he said to me afterwards "this is going to be a problem, those boys are going to need help, they are going to despise the media, blame them for her death, yet the media will be a part of their lives."

"Yes, they are," he says, quietly.

I ask whether, in Paris a few months earlier, on an official visit, posing for hundreds of photographers outside the Elysée Palace with former President Francois Hollande, he looked at the media's massed ranks and wonder if any of them were among those who chased her that night when she was killed as she went out with Dodi al-Fayed?

"I'm afraid those are the kind of things I have just had to come to terms with. It is so hard to explain, using only words, what it was like for my mother. If I could only bring out what I saw and what happened in my mother's life and death, and the role the media played in that, that is the only way people would ever understand it. I can try to explain it in words but to live it, see it, breathe it, you cannot explain how horrendous it was for her."

Perhaps looking for some good out of it all, he says that he thinks there has been 'some improvement' in the way his own children are treated by the media, and believes the reaction to her death was a big factor in diminishing the aforementioned British 'stiff upper lip' approach to emotional struggle, and that it has changed the way we mourn, for ever, citing the reactions to the deaths of George Michael and David Bowie as examples. "The massive outpouring around her death has really changed the British psyche, for the better."

Not all agree with him, including some close to home. A few weeks after the Heads Together films were released, and Prince Harry had spoken to a mental health blogger about how he had needed counseling to deal with the aftermath of his mother's death, The Sunday Times ran a story quoting anonymous sources that The Queen wished her grandsons to desist from further baring of their hearts and souls. I have enough experience of Sunday paper stories not to be certain if there was any truth in this one. But I hope not. And if there was, I hope they ignore it, because their campaign is making a real difference, by normalising conversations about mental health. That can only be a good thing, because I know plenty of people who find mental illness hard enough, but who find the stigma and taboo – particularly in the workplace – even harder.

"Practically everything in my charitable life in the end is to do with mental health," he says, explaining why he has alighted upon this issue as his current main priority. "Whether it be homelessness, veterans' welfare, my wife and the work she is doing on addiction, so much of what we do comes back to mental health.

"Also, if I think about my current job [with the Air Ambulance service], my first job there was a suicide and it really affected me. Not just the person who lost their life, but the people they leave behind. One of the stats I was given was that just in the area we cover in the East of England – my base is in Cambridge - there are five attempted suicides every day. Yet suicide is still just not talked about. So people have the pain of loss, but also the stigma and the taboo means they are sometimes ashamed even to talk about how a lover, a partner, a brother, a sister, a best friend, how they died. That stat - five attempted suicides in the East Anglia region alone - it blew my mind, I thought "oh my God this is such a big issue.'"

I also know he and Kate have made a private visit to Britain's only suicide sanctuary, The Maytree, of which I am a patron, in North London. "The thing that really made an impression on me, it wasn't just the feelings of the people, the pain they were going through and the care for them, it was that this is the only place of its kind in the UK. It may be the only one in the whole of Europe, and I thought, this is terrifying, it really is, there should be more places like this, where people can go when they're desperate. I have spoken to suicide groups and having been through personal grief myself I had an inkling of what to expect but it was all so raw. When someone does end their own life, so many questions, people feeling guilty, why didn't we see it, why didn't we do more, and all surrounded by this massive taboo. I found it eye opening, so revealing as to what goes on in people's minds."

As for the specific goals and outcomes for the Heads Together campaign, a big one has already been achieved, the 2017 London Marathon having been labeled 'the mental health marathon,' with Heads Together the official cause. He was keen to run it himself, but with the terrorism alert high, his security team had other ideas. In any event, he has bigger goals. "Ultimately smashing the taboo is our biggest aim. We cannot go anywhere much until that is done. People can't access services till they feel less ashamed, so we must tackle the taboo, the stigma, for goodness sake, this is the 21st century. And I have been shocked, really shocked, how many people live in fear and in silence because of their mental illness, I just do not understand it.

"I know I come across a lot of the time as quite reserved and shy, I don't always have my emotions brewing, but behind closed doors I think about all the issues, I get very passionate about things. I rely on people around me for opinions, and I am a great believer in communication on these issues. I cannot understand how families, even behind closed doors, still find it so hard to talk about it. I am shocked that we are so worried about saying anything about the true feelings we have. Because mental illness is inside our heads, invisible, it means others tread so carefully, and people don't know what to say, whereas if you have a broken leg in plaster, everyone knows what to say."

On the twentieth anniversary of his mother's death, as I know from the plethora of bids from documentary makers all around the globe, there will be a lot of focus on Diana, and on her legacy. He admits he is slightly dreading the occasion, though in addition to the interview with me, he and Harry have been interviewed both by the BBC and ITV, and given very personal and loving accounts of their memories of their mother. Some of those interviews feature in a BBC documentary about the final week before Diana's death, called Diana, 7 Days. "I am not looking forward to it, [the anniversary] no, but I am in a better place about it than I have been for a long time, where I can talk about her more openly, talk about her more honestly, and I can remember her better, and publicly talk about her better.

"It has taken me almost twenty years to get to that stage. I still find it difficult now because at the time it was so raw. And also it is not like most people's grief, because everyone else knows about it, everyone knows the story, everyone knows her. It is a different situation for most people who lose someone they love, it can be hidden away or they can choose if they want to share their story. I don't have that choice really. Everyone has seen it all."

"How much has the passing of time helped?" I ask. He seems unconvinced. "Well, they do say time is a healer, but I don't think it heals fully. It helps you deal with it better. I don't think it ever fully heals."

"Is there a part of you," I wonder, "that in a way doesn't want it to heal fully because for that to happen might make her feel more distant? So you feel the need to stay strongly attached? If grief is the price we pay for love, maybe you want to keep the grief out of fear that loss of grief means you love her less?"

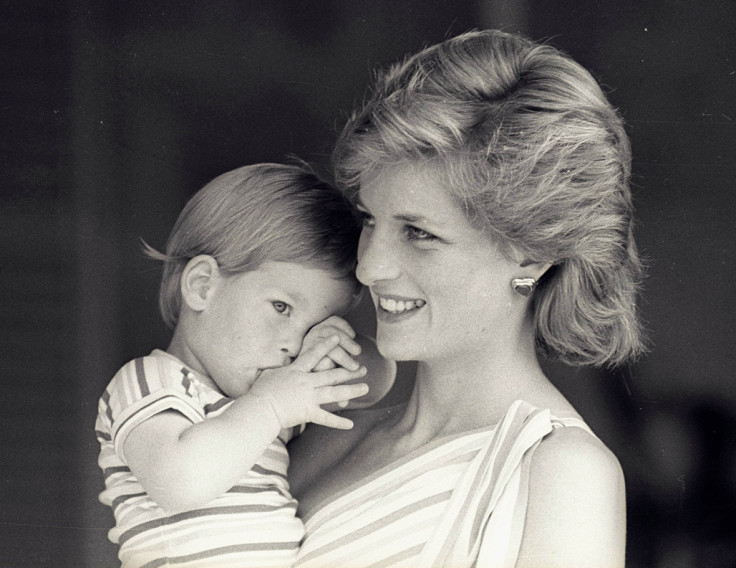

He shakes his head. "One thing I can always say about my mother is that she smothered Harry and me in love. Twenty years on I still feel the love she gave us and that is testament to her massive heart and her amazing ability to be a great mother." It is in large part, both of them have said, what has kept them going through difficult times. "She would not want us to be sad," he says, "she would want us to get out there and live."

I would love her to have met Catherine and to have seen the children grow up. It makes me sad that she won't, that they will never know her.

We talk a little about how different Britain might have been if she was still here – I was thinking more of the cultural and even political impact she might have had. "I have thought about that, but mainly from my own perspective," he says. "I would like to have had her advice. I would love her to have met Catherine and to have seen the children grow up. It makes me sad that she won't, that they will never know her."

Instead, in addition to the millions of photos and the thousands of hours of TV footage of the grandmother they never met, he says he keeps her memory alive for George and Charlotte by telling them stories of "Granny Diana."

As for the public Diana, "I think she would have carried on, really getting stuck into various causes and making change. If you look at some of the issues she focused on, leprosy, Aids, landmines, homelessness, she went for some tough areas. She would have carried on with that."

"She was an extraordinary woman," I say.

"She was," he replies, the sadness that has been such a part of his life for two decades suddenly all too clear; his love for his mother, a love he had to share with millions around the world who thought they knew her, all too clear as well.

To see the Heads Together films, go to www.headstogether.org.uk

The Samaritans provides a free support service for those who need to talk to someone in the UK and Republic of Ireland. It can be contacted via Samaritans.org or by calling 116 123 (UK) or 116 123 (ROI), 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Alastair Campbell is Ambassador for Time to Change mental health campaign.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.