Is the bedroom tax worth its human cost?

Critics argue limited successes of bedroom tax do not justify the devastating impact on many of those affected.

Mandy Talbot needs all the financial help she can get to afford the "bedroom tax", the label for a cut in housing benefit for claimants in social housing with spare bedrooms. She borrows from friends and family, straining relationships, to keep the roof over her head.

The 51-year-old grandmother became unable to work after a lifetime of striving, including 18 years running her own pub and hotel, because of a back injury. She took time off to recover, now relying on the welfare system into which she had paid for many years, hoping to work again soon.

When she asked for extra financial support from the local council, called a "Discretionary Housing Payment" (DHP), allocated to those in desperate need because of welfare cuts, her request was denied — then she had a heart attack. But even that was not enough to secure a DHP from the under-pressure council, despite her need to rest and recuperate on returning home after nine days in hospital. Go and use a foodbank if you have to, the Lancashire council allegedly told her.

"I know how I feel and I've got a support network," Talbot says, aware that, despite her difficulties, she is far from the worst-affected. "What about people without a support network? I have actually sat here at times, particularly after I had a heart attack because I got a bit depressed and thought I don't see the point of my life anymore."

She adds: "I'm a write-off to the government, really. Seriously, I do believe they'd actually like me just to put a rope around my neck because then I'd be one less person they've got to shell out for."

Talbot wants to move out of the two-bedroom house in which she lives alone. But like many others hit by the bedroom tax, she cannot find a smaller property. She is trapped. Until she can find work, she will just have to struggle on, around £28 a week worse-off because of the bedroom tax. That is a lot of money to find for someone who gets just £128.60 a fortnight in jobseeker's allowance.

More than three years on from the introduction of the bedroom tax, the policy has seen limited success at what critics argue is a substantial human cost. Now Theresa May, the new prime minister entering the job in a whirl of rhetoric about helping those with the least in society, faces fresh calls to scrap it.

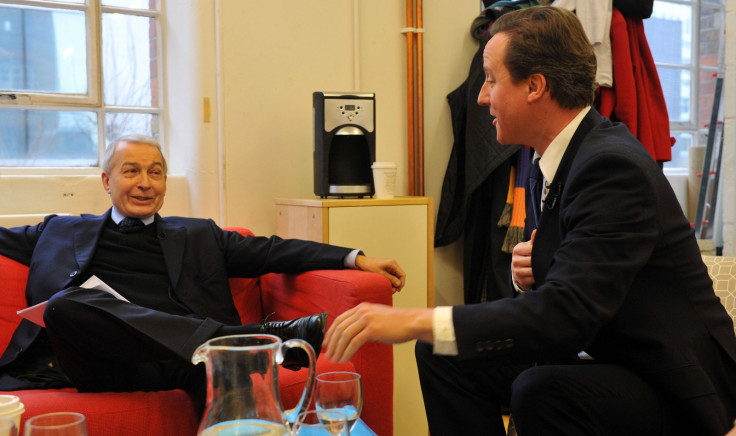

"It would be an early Christmas present for my constituents if it were scrapped altogether," says Frank Field, Labour MP for Birkenhead and chairman of the Work and Pensions Committee in the House of Commons. "The idea that a welfare reform can be deemed a success when it has resulted in parents relying on candles to keep themselves and their children warm, is barmy beyond belief."

"The policy should be abolished, as it has in Scotland, not changed," says Professor Anne Power, head of the Housing and Communities department at the London School of Economics (LSE). "The human cost of the bedroom tax has been huge and it hasn't been worth it. We know of lots of cases of real suffering, anguish and hardship caused by the policy. It has not been fairly applied."

People are cutting back on food and heating rather than not paying the rent

At the end of 2015, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) published its "final evaluation" of the removal of the spare room subsidy, officialese for the bedroom tax. It was conducted by the research firm Ipsos MORI and academics from the University of Cambridge's Centre for Housing & Planning Research.

"There's some evidence that it met some of [its aims] to some degree — there isn't overwhelming evidence that it met them all," says Anna Clarke, senior research associate at the Cambridge centre and one of the authors of the report.

When unveiled in 2012 by the then work and pensions secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, the bedroom tax was framed as "fairness" to taxpayers, who should not have to subsidise spare rooms for social housing tenants on housing benefit.

Its specific aims were more efficient use of the social housing stock while reducing under-occupancy and overcrowding; nudging more people into employment and higher-paid work; and saving public money on housing benefit spending.

But since coming into force in April 2013, it has had marginal success in each area, leaving some to question whether the human cost of the bedroom tax — which has slashed the incomes of some of the most vulnerable people in society — is worth it.

"'Is it worth it' is not something we were able to look at, or make judgments on, or search hard for the evidence for," Clarke says. "We were having to just look at does it meet those certain objectives."

The policy is deeply divisive. Opposition has grown sharply amid a firestorm of criticism in the media and human interest stories from those worst-affected. Polling by YouGov shows that between March 2013 and July 2014, support fell from 49% to 41% and opposition rose from 38% to 49% — a reversal in attitudes.

"It was a sensitive piece of research and as always with that kind of project, especially with a lot of interview data there's an element of subjectivity around exactly what you emphasise or which quotations you use, which means the final wording of the report goes backwards and forwards a lot before publication.

"I'm happy with what went out in the end. I do feel the essence of it is as it should have been, given what it had been asked to look at," Clarke says of the final evaluation.

Though it was the "final" evaluation, Clarke says the Cambridge report should not be the last word on the effectiveness of the bedroom tax. What happens over a longer-term to those with arrears, overcrowding, and mobility in the social housing sector are open issues.

"I don't think the DWP have any interest in commissioning anything," Clarke says, though she is hopeful others who work in the sector — housing associations, for example, will fund a separate research.

The DWP said it has overseen two comprehensive evaluations of the policy and publishes quarterly statistics. "Removing the spare room subsidy has restored fairness to the system, and the number of households subject to a reduction is falling," stated a DWP spokesman.

"We know that there are cases where people may need extra support and that's why we have given councils nearly £500m of funding to provide discretionary payments to those that need them, with a further £870m to be provided up to 2020."

Under-occupancy fell and more people were downsizing in the social sector, according to the final evaluation, but in absolute terms these were still a very small portion of all households.

From the policy's introduction to Autumn 2014, 45,000 households in England affected by the bedroom tax had successfully downsized, leaving 471,887 still affected. There are 3.9 million households in England's social sector alone, suggesting those who downsized accounted for just 1.15%.

The English Housing Survey found overcrowding in both council-owned and housing association properties had been generally constant since 2012-13. Just 5% of those hit by the bedroom tax found work between 2013 and 2014. Only a fifth of those who were no longer affected cited higher earnings.

The £490m a year savings the DWP says it would make are a fraction of the government's overall welfare budget — just 0.22% of social protection spending in 2013-14, for example.

People at the very bottom of the pile today are being asked to pay for the mistakes of successive generations of planners who failed to build enough one and two bedroom homes.

And the additional government spending required for DHPs, shoring up English and Welsh councils paying out primarily because of the bedroom tax, weakens the financial benefit for the public purse.

Moreover, there is also the potential for a false economy if families leave the social sector to downsize. Two bedrooms in the private rental market often costs more than three in the social sector. They may no longer be under-occupying their home, but their housing benefit claim may be higher.

Councils and housing associations are shouldering additional administrative costs from the bedroom tax, such as managing growing transfer lists for those wanting to downsize their home and chasing arrears from those who can no longer afford their rent.

The English Housing Survey says 37.4% of those in social rented housing who had fallen into arrears because of benefit cuts blamed the bedroom tax specifically, or 57,485 households. A 2014 report by the research firm Ipsos Mori on behalf of the National Housing Federation estimated housing associations would spend on average £109,000 each in a single year mitigating the effects of the bedroom tax.

Councillor Philip Glanville, mayor of the London borough of Hackney, where he previously ran the housing team, says the council will not evict people "based solely on bedroom tax arrears" because homelessness services would then have to pick up the pieces.

"But that does mean that arrears are ticking up in the background and so that obviously causes stress to people," he says.

A general lack of smaller homes hinders downsizing. "People at the very bottom of the pile today are being asked to pay for the mistakes of successive generations of planners who failed to build enough one and two-bedroom homes," Field says. But the government says there are 1.4 million one-bedroom homes across the social sector, and that landlords are adapting by building smaller properties in response to higher demand because of the bedroom tax.

Others do not want to leave their communities and support networks, cutting back on essentials instead. "People do prioritise rent above all else, even when they're struggling and the extent to which people were rational, and did put all their efforts into paying their rent, even when the evidence suggests there really wasn't a lot else to cut back on — they were cutting back on food and heating rather than not paying the rent," Clarke says.

A 2015 study by academics from Newcastle University, based on a survey of 38 social housing tenants and 12 service providers, found evidence that the bedroom tax "has increased poverty and had broad-ranging adverse effects on health, well-being and social relationships within this community".

"The human cost of it has been exponential," says Councillor Penny Holbrook, who represents the Stockland Green ward in Birmingham, one of the worst-affected areas by the bedroom tax. She says just 10 of the 300 cases she has seen have moved into smaller accommodation.

"There's no way we can justify the amount of people who have been affected by this and the amount who have been affected with no choice. It was simply never going to work because there was never the volume of property for people to move into."

Grieving families in receipt of housing benefit are given a year's grace by the DWP before the bedroom tax applies. The teenage daughter of one of Holbrook's constituents was murdered a couple of years ago. A year passed, and with the girl's bedroom empty for the most terrible of reasons, her mother had her housing benefit cut for under-occupying the house, Holbrook says.

Another constituent hit by the bedroom tax is a woman with a disability and incontinence. She lives with her husband in a two-bedroom property. Because of her disability, they sleep in separate rooms. But as a married couple they are only entitled to the full housing benefit for a one bedroom home. The council told her it was the couple's choice to live like that.

The Cambridge evaluation recognised that disabled tenants in particular struggled with downsizing because they cannot find a suitable alternative, with room for specialist equipment, for example. "The worst cases are people who are disabled or need a second room for respite, but who don't have high-level disability status, so they're not exempt from the bedroom tax," Glanville says.

The government says it is committing over £1bn of financial support for disabled tenants by 2020, particularly those who are most vulnerable or unable to move because of a need for specialist equipment.

Holbrook explains you cannot look at the bedroom tax in isolation. The housing welfare cuts pile on top of one another, from the removal of benefits for the under-25s to the room rate for people aged 25-35, to the Local Housing Allowance caps for private rental homes.

"If you look at it as a raft of measures, what we've done is taken a massive housing shortage and imposed all of the consequence of that on those least able to deal with it," she says. But the government insists it still has a robust safety net in place, despite the heavy cuts to welfare, with £90bn still being spent on benefits for those on low incomes every year.

Mandy Talbot's grandson was born with a serious heart condition. He had two major operations and was in intensive care hundreds of miles away in the south west of England. "Do you know why I couldn't go down and see him? Because I had bedroom tax to pay," Talbot says.

She is trying hard to set up her own business so she can start again and move on from the bedroom tax. She recently borrowed money to retrain as a nail technician — yet more debt — hoping to take a space in a nearby salon. A nail table is on order.

Talbot claimed Disability Living Allowance when her back was at its worst. But as soon as she felt able to do at least some work, the self-styled "Mrs Honest" did not reapply for disability benefit, leaving her significantly worse-off.

"I don't have a free bus pass because I came off DLA, thinking I was doing the right thing for my bloody country," Talbot says. Now she has to find money to fund her car — a need, not a luxury. "I rely on my car to get around because I can't always walk."

Life is difficult. Her family give her food parcels and cook meals to support her where they can, and often hard cash when she goes "cap in hand". Instead of moving onwards and upwards, Talbot finds herself having to focus relentlessly on the complex minutiae of managing every last penny of her budget. The money coming in never matches her outgoings. Her internet was the last thing to be cut off.

"It's like bedroom tax takes over your life," Talbot says. She's trying to reclaim it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.