Black hole with very weak magnetic field baffles scientists

Researchers measured the precise strength of the black holes' magnetism for the first time.

In a surprise discovery, an international team of astronomers from the University of Florida has found that a black hole, located some 8,000 light years away from the Earth, has much lower magnetism than previously thought.

It was the first occasion when scientists were able to precisely measure a black hole's magnetism and scientists believe the achievement will facilitate a deeper understanding of black holes and their magnetism.

Black holes are dark cosmic voids that suck in anything coming near them — stars, planets, or any other space objects. They are believed to exist across different parts of the universe in various sizes such as the supermassive black hole located at the centre our own galaxy.

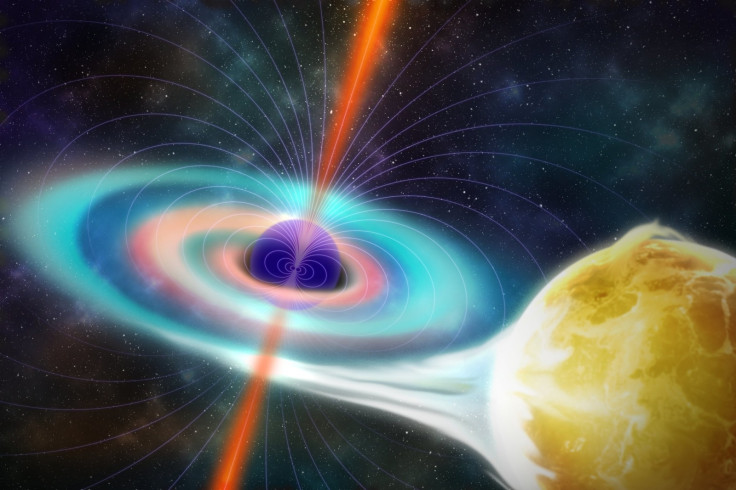

The black hole researched by the international team is part of a binary system called V404 Cygni. It has a mass equalling 10 suns and is likely sucking in materials from a nearby star.

As the 40-mile-wide black hole gradually devours the material, it also ejects beams or jets of charged particles at light speeds. It is believed that the magnetic field surrounding these voids have some role to play in these outbursts, but the exact physics of the process has long been a point of debate.

Studying one such outburst from V404 Cygni's black hole dating back to 2015, astronomers have precisely estimated the strength of its magnetic field. The scientists used the lens mirror of the 34-foot Gran Telescopio Canarias — the world's largest telescope co-owned by the University — to study the occurrence.

After observing the short-lived event, which lasted for about two weeks, the team was able to determine that the magnetic energy around the black hole is nearly 400 times lower than what has been estimated in the past.

"To observe it was something that happens once or twice in one's career," says Yigit Dalilar, lead author of the study published in journal Science, referring to the rare occurrence. "This discovery puts us one step closer to understanding how the universe works."

The last time the same black hole had a similar episode was in 1989, a report in Phys.org notes.

These findings could provide astronomers new insights into the behaviour of black holes, including how they feed on cosmic objects and drive out these so-called "jets" at light speed.

The report adds, studying the behaviour of matter under the extreme conditions created by a black hole could even broaden the limits of nuclear fusion power and GPS systems.

"The question is, how do you do that?" study co-author Stephen Eikenberry said. "Our surprisingly low measurements will force new constraints on theoretical models that previously focused on strong magnetic fields accelerating and directing the jet flows. We weren't expecting this, so it changes much of what we thought we knew."