Brexit voters and Britain First supporters are more likely to believe conspiracy theories

KEY POINTS

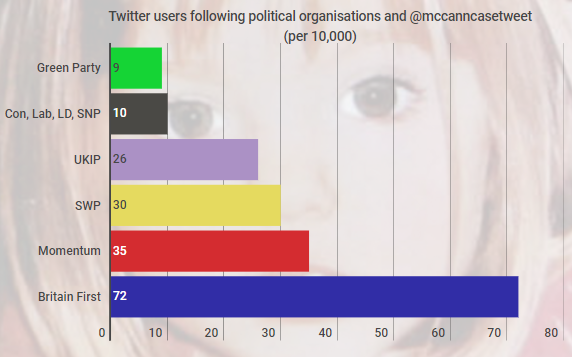

- IBTimes UK analyses Twitter data to uncover far-right's obsession with Madeleine McCann's disappearance.

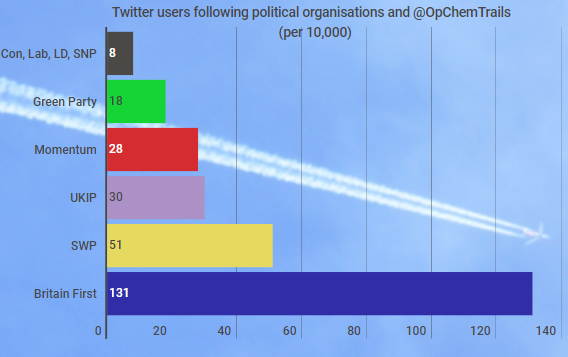

- Britain First supporters also more likely to track UFO sighting and believe in the debunked "chemtrails theory".

- Momentum, the Jeremy Corbyn support machine, more prone to conspiracies than UK Labour.

Britain First supporters are seven times more likely to believe that Madeleine McCann's parents had a hand in her death than are supporters of mainstream UK political parties, an investigation by IBTimes UK has revealed.

Supporters of the far-right organisation – recently catapulted to global attention when Donald Trump retweeted violent anti-Muslim videos posted by deputy leader Jayda Fransen – are also 16 times more likely to think aircraft could be secretly releasing harmful chemicals into the sky and five times more likely to be interested in potential UFO sightings.

The findings come from an exclusive analysis of Twitter data – conducted a week before the group gained international notoriety – which shows that followers of far-right and far-left political groups are more susceptible to conspiracy theories, and that those on the far-right are most prone.

The analysis also reveals that:

- Hard Brexit supporters are more susceptible to conspiracy theories than people determined to keep Britain in the EU

- Momentum supporters are over three times more likely to suspect a Madeleine McCann cover-up than Labour Party supporters

- Sinn Fein and DUP supporters have more interest in conspiracy theories than major UK political parties

Experts said that political extremism and believing in conspiracy theories were both symptoms of the same underlying causes, with one warning that Brexit could push yet more people into the abyss.

Madeleine McCann conspiracies and the political fringes

The internet is awash with Madeleine McCann conspiracy theories, alleging that Kate and Gerry McCann, accidentally or otherwise, killed their daughter and covered up the death with the help of British law enforcement.

Madeleine Case Tweets (@mccanncasetweet) is a Twitter account disseminating snippets of miscellaneous amateur detective work from the online community. It had 5,739 followers when IBTimes UK crunched the data on 20 November.

Britain First, who declined to comment on the findings, had just over 24,000 followers at the same time, of which 174 also followed @mccanncasetweet, amounting to 72 per 10,000 – over seven times the frequency of followers of the largest four parties at Westminster (Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats and the Scottish National Party (SNP).

The next most likely group of people to follow the account were followers of Momentum, the Jeremy Corbyn support machine, at 35 per 10,000. Followers of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), the loudest voice on Britain's hard-left before Momentum's arrival, and the UK Independence Party (UKIP) were roughly three times more likely to follow the account than the median of the four major parties.

Only Green Party followers were less likely to follow @mccanncasetweet than the big four. Get the full data here.

What is a conspiracy theory?

Most simply a conspiracy theory is a belief that a group of people, often powerful, have secretly colluded to carry out a malevolent action.

They provide explanations for world events that differ from widely accepted narratives.

Conspiracy theories can be, and on occasion have been, true. However, they are often elaborate and unfalsifiable, with adherents absorbing any facts appearing to refute them as further evidence of the grand conspiracy.

The findings are consistent with several academic studies into the relationship between political beliefs and conspiracy theories. They did not surprise Dr Jan-Willem van Prooijen, a social psychologist who has conducted extensive research on the topic.

"Political extremism is characterised by a very clear cut perception of the world," he said. "It's a form of black and white thinking where people are either good or bad, and things are right or wrong.

"The reason why people at the extremes believe conspiracy theories more strongly is because they think solutions to societal problems are actually quite simple, so an economic crisis isn't caused by a multitude of factors – it's a bunch of bankers causing it deliberately."

Chemtrails conspiracies and the political fringes

How we crunched the data

IBTimes UK used an analytics tool, follwerwonk, to compare the users who followed each of the political groups' Twitter accounts with followers of three conspiracy accounts on 20 and 21 November.

The exercise has a some limitations, chiefly that following a political group's account does not necessarily mean a person supports them, and following a conspiracy account does not necessarily mean a person believes in the conspiracy.

However, the results are consistent with peer-reviewed academic studies.

Op Chem Trails (@opchemtrails) is a Twitter account dedicated to the debunked theory that the cloud trails left by aircraft are not a byproduct of their engines but chemical agents designed to manipulate or harm the public.

Comparing the followers of the same UK political organisations with the 11,876 @opchemtrails followers on 21 November yielded similar but more dramatic results than with the @mccanncasetweet account. Britain First led the way by a clear distance: 131 followers per 10,000 followed @opchemtrails – more than 16 times the median of the largest four parties.

All of the groups outside the four major political parties had followers that were significantly more likely to follow the account, with the Greens no longer the exception to the rule. Get the full data here.

Who are Britain First?

Britain First was formed in 2011 by former members of the British National Party. The group, which primarily campaigns against what it sees as the Islamisation of the UK, has stood unsuccessfully at national, regional and European elections.

However, the it has a huge social media presence, and boasted more Facebook followers than any other UK political party – even before Donald Trump catapulted them to global attention by retweeting videos posted by deputy leader Jayda Fransen.

The group is currently led by former BNP councillor Paul Golding, who stood against Sadiq Khan for the London mayoralty in 2016, turning his back on the Muslim mayor as he gave his victory speech.

Fransen and Golding are currently charged with religiously aggravated harassment in relation to their behaviour around the trial of a group of Muslim sex offenders in Kent. Fransen faces a separate charge of religiously aggravated harassment over a speech she made in Belfast.

Van Prooijen said the data were consistent with previous studies carried out in Western countries, which found that while people on both the far-left and far-right were more inclined towards conspiracy theories, the far-right tended to be more so.

He offered a possible psychological explanation for this – "the rigidity of the right" – which claims that right-wingers have a greater need for security and certainty, leading them to gravitate towards simple, clear-cut explanations of the world.

However, he also thought the results might be explained by the actual content of the different ideologies competing across the political spectrum. "Maybe the right extreme is slightly more extreme in Western societies than the left extreme," he said. "This may be different in other parts of the world."

His suggestion is supported by the latest Home Office statistics, which show that 5% of people in custody for terror-related offences admitted to a right-wing ideology, compared with 91% Islamic extremists and 4% Other. While the National Police Chiefs council reported that 8% of terror arrests had been flagged as "extreme right wing" in the year to May.

These statistics are brought into focus by Thomas Mair, who shot dead Labour MP Jo Cox outside her constituency surgery in June 2016 while shouting "Britain first". It would appear that the contemporary far-right embody a more extreme politics than the left in Britain.

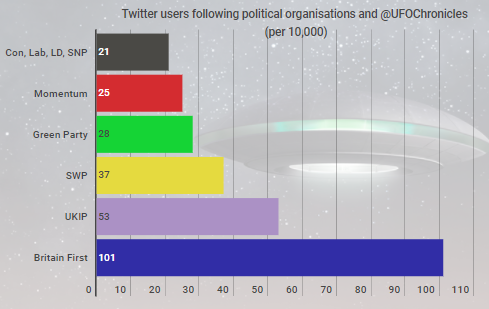

UFO sightings and the political fringes

Questions about the authenticity of the videos uploaded to Twitter by Jayda Fransen and retweeted by Donald Trump are not the first to implicate the group in spreading fake news.

An investigation by the Press Association earlier this year found a string of misleading videos published through the group's social media channels.

These included one showing a "huge crowd of migrant Muslims" attacking German police, but was in fact an anti-fascist demonstration from 2011.

Another post entitled "Muslim migrants in Australia thought they are above the law!" featured a man who told the Press Association he was actually born in Australia.

Another from Paul Golding allegedly showed migrants in Europe attacking a woman – but the footage was actually of a mugging carried out by children on a woman in Brazil.

A familiar pattern emerged when the groups' followers were compared with those of The UFO Chronicles (@ufochronicles), which had 80,542 followers on 21 November. The account, which documents alleged UFO sightings from around the world, has a much larger following than @mccanncasetweet and @opchemtrails, and supporters of the four major parties were much more likely to follow it. Get the full data here.

Clearly, people engaging with politics at the edges are more susceptible to conspiracy theories, with those on the far-right most prone, but why?

Political exclusion and conspiracy beliefs

In the era of so-called "fake news" and the rise of populism, it is natural to imagine a causal relationship between believing in conspiracy theories and fringe politics. Indeed, the tendencies may feed off one another. However, van Prooijen argued that there is a much more fundamental relationship between conspiracy beliefs and extremism.

"They're symptoms of the same underlying sentiment," he said. "The same reason populous leaders got elected or Brexit happened in the first place are also the causes of conspiracy theories."

He claimed marginalised people are more susceptible to conspiracy theories and alt politics because they feel threatened, uncertain about their futures and lacking control over their lives. These feelings make them crave a simple, monochrome view of the world that underlies both conspiracy theorising and extreme politics.

He gave an example: "Large groups who don't profit from globalisation and may actually be harmed by it."

Dr Hugo Drochon, a political theorist at the University of Cambridge Conspiracy and Democracy project, agreed with van Prooijen that the propensity to believe in conspiracy theories and to engage with fringe politics were borne out of the same causes.

"It's not that conspiracy theories leads to disenchantment with democracy," he said. "It's rather that disenchantment with democracy leads to conspiracy theories – it reflects a deeper malaise within the democratic society."

Drochon teamed up with YouGov to survey conspiracy beliefs among people in several countries in 2016. Their study found that people who feel excluded from the democratic process – that their vote does not count for anything – are much more likely to believe in things like a secret cabal controlling all world events. Britain First, which has never successfully contested an election and was deregistered by the Electoral Commission earlier this month, perfectly fits the archetype of a movement for the politically excluded.

However, IBTimes UK's analysis of Twitter users following Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) – Northern Ireland's biggest two political entities – throws a more nuanced light on the issue of political exclusion.

People who follow the DUP or Sinn Fein on Twitter are more likely to follow the three conspiracy accounts than are followers of the four main Westminster parties. In addition, they are (nearly always) less likely to do so than followers of the fringe parties parties. Get the full data here.

This could reflect that while Sinn Fein and the DUP's supporters are clearly engaged in the democratic process, and do see their votes transformed into representation, they may feel democratically excluded by the fragility of Northern Ireland's power-sharing agreement, which is prone to collapse and intervention from Westminster (a Tory minister recently set its budget). Drochon said the findings were consistent with his and other studies, which had shown that even the politically involved are more likely to believe in conspiracies when they are out of power.

Sinn Fein and the DUP were mostly sandwiched between the mainstream parties and the less extreme fringe groups in the rankings, and they were always dwarfed by Britain First. Drochon said: "It's not that conspiracy theorising doesn't happen on the political spectrum – it definitely does – but the main action is happening at the extremes, where there's complete political exclusion – where they're not in the political game at all"

Are conspiracy theories on the rise? What about Brexit?

Van Prooijen and Drochon both cited an American study, which reviewed 120,000 letters sent to the editors of daily newspapers from 1890 to 2010 and found that there was no long-term upward trend in conspiracy theorising during the period. However, they were also both open to the possibility that the continuing aftermath of the 2007 global financial crisis may have created a recent spike. In fact, that would be expected, given the rise of populism, which they both argue is symptomatic of the same underlying causes.

Which brings us to Brexit.

IBTimes UK compared the Twitter followers of Leave Means Leave (@leavemnsleave) – which campaigns "unequivocally" for leaving the single market, customs union and jurisdiction of the European Courts – and Remain In EU (@remain_eu), an unofficial account started after the June 2016 referendum, which campaigns for reversing the Article 50 process.

Leave means Leave supporters were much more inclined towards conspiracy theories than people with the idea that Britain can stay in the EU. This is unsurprising given that the mainstream political parties all backed remain, while the right wing fringe parties and the SWP backed Leave. Even though Momentum is officially pro-EU, many of the older leftists in the group are, like Jeremy Corbyn, Eurosceptic at best.

Some 141 per 10,000 Leave Means Leave followers also follow @mccanncasetweet – the highest convergence between any single group's followers and any of the three theories. Interestingly though, it is only three and a half times more than the 42 per 10,000 Remain in EU followers who also follow the acount. Get the full data here.

Across the board, Remain in EU followers are much more likely to be interested in conspiracy theories than followers of mainstream political parties. Van Prooijen said: "A core predictor of belief in conspiracy theories is a feeling of powerlessness in relation to leaders – sentiments such as 'the leaders of our country don't listen to us'."

That sentiment is currently pouring out of both 'reverse-the-vote' Remainers and diehard-Brexiteers. And when Britain and the EU's new relationship is finally cobbled together, it will definitely leave one group, and probably both, feeling excluded from the democratic process.

Drochon is hoping to conduct another round of his survey with YouGov in 2018, allowing comparison with the 2016 poll, which was taken shortly before the referendum: "Our hypothesis will be that there has been an increase in conspiracy theories in Great Britain between 2016 and 2018," he said.

"Brexit has revealed that this country is divided, and in many ways that division is what leads to higher conspiracy theorising."