Buy-to-let clampdown explained: Four ways the UK tax changes would be bad for landlords

Tory MP George Osborne's latest Budget has clearly biased future savings against buy-to-let investments in the residential property market, and in favour of other, financial investments instead.

There are two legs to this stealth attack on the UK buy-to-let sector, as both the Conservative chancellor and the Bank of England attempt to prevent the property price bubble that has inflated in London and the South East of England from getting any worse.

Recent tax changes are unfavourable for buy-to-let

A number of less favourable tax changes relating to buy-to-let properties are coming into force as of the new tax year on 6 April 2016. Here are four ways the tax changes would be bad for landlords.

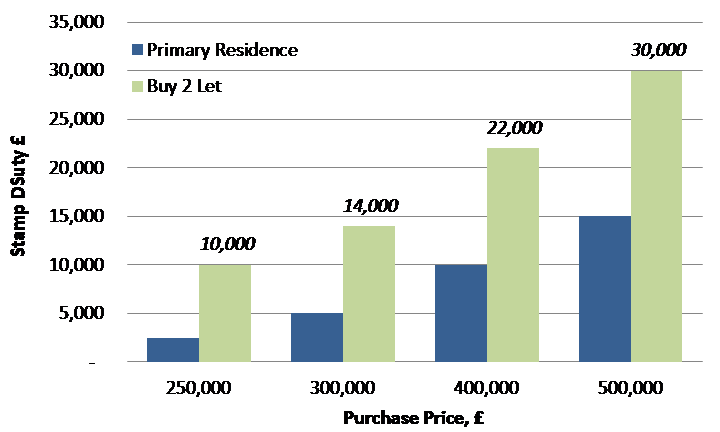

1) Stamp duty on buying secondary properties – any property after your primary home – has gone up. All buy-to-let properties worth more than £40,000 (that is, pretty much any buy-to-let property investment) would now attract a stamp duty surcharge of 3%.

This can now eat massively into even long-0term returns on buy-to-let property investments, with stamp duty on a £500,000 house for buy to let now costing £30,000, or 6% of the purchase price (see Chart 1).

2) Income-tax relief on mortgage interest cut – whereas tax relief on mortgage interest for buy-to-let properties was up to now at the landlord's marginal rate of income tax (up to 45%), it will now only be allowable at 20%. No change for basic-rate taxpayers, but a big effective increase in income tax (via the lower tax relief from buy-to-let mortgage interest paid) for higher-rate taxpayers.

3) Income-tax charged on buy-to-let turnover not income – now this is a crafty change that is not obvious, but nonetheless potentially expensive for buy-to-let landlords. This is best illustrated with a quick example:

Our example buy-to-let landlord Adam has a house rented out currently worth £250,000, on which he earns a gross rental yield (before costs for maintaining the house in good order) of 4%. That is, he receives £10,000 in rent from his tenants a year.

From this, he could previously deduct 10% from his rental income for wear and tear without any need for bills to prove this spending. Now, he would need to provide bills for any spending he has incurred to maintain the house.

Let's say that Adam didn't spend anything on the house, as it was relatively new. So the £1,000 he could have deducted from his taxable income (10% of his £10,000 gross rental income) can no longer be deducted.

On top of that, before the tax changes he could then have deducted his entire mortgage interest cost. Let's say that this amounted to £8,000 a year (4% on a £200,000 interest-only mortgage). So Adam would have previously paid income tax on net rental income of:

£10,000 minus £1,000 and £8,000 equals £1,000. Some 40% marginal income tax on £1,000 equals £400 in income tax, leaving Adam with a net profit after tax of £1,600 annually on his house from the rent alone.

From 2020, when the new buy-to-let rules are fully in force:

Adam still receives £10,000 rental income from tenants. But now he would pay 40% tax on the £10,000 (£4,000). From this, he can only then deduct 20%, leaving a £3,200 tax bill to pay. As there were no maintenance expenses, there is nothing further to deduct.

Adam has thus received £10,000 in rent, but paid £8,000 mortgage interest to his bank and £3,200 to HMRC, meaning that rather than turning a profit, the buy-to-let house is now costing him £1,200 a year, even before taking into account any maintenance spending.

This is a swing of £1,600 a year – a large amount when you add this up over the course of 15 or 20 years.

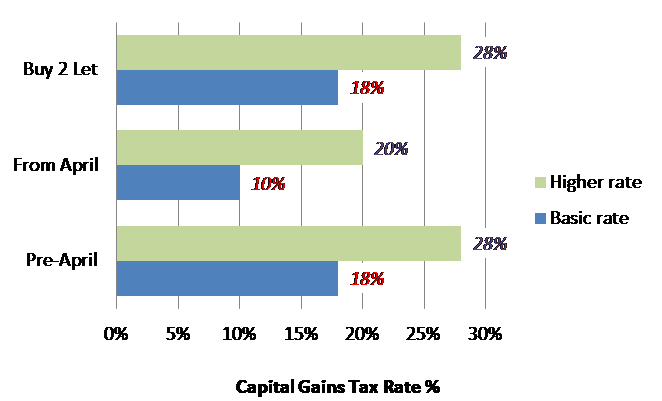

4) Capital gains tax rates unchanged for property – whereas all other investments now attract a lower rate of capital gains tax (CGT) upon selling the investment, falling from 18% at the basic rate of CGT to just 10% from April. However, the CGT rate remains unchanged for property investments, making other types of investment more attractive on a CGT basis.

Now, this doesn't affect the attractiveness of owning your own (primary) home to live in, as there is still no capital gains tax to pay if you sell this, but it does reduce the relative attractiveness of buy-to-let properties relative to other investments.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.