Chibok girl: How I escaped Boko Haram

Sa'a got away on the night of the school raid in northern Nigeria – hundreds of others did not.

Sa'a was asleep when Boko Haram came. She awoke to the roar of engines, gunshots and shouts of 'Allahu Akbar' as the fighters burst into her dorm room in Chibok, Borno State, Nigeria, on 14 April, 2014, and ordered all the girls outside. Then they burned the school to the ground.

"One of them explained to us that [...] whatever they asked us to do, we had to do: that was when we realised that they were the Boko Haram," said Sa'a.

It was not the first time that the then 18-year-old had encountered the Islamist militia that in 2015 would pledge allegiance to Isis. Not only had Boko Haram attacked Sa'a's previous school, but like most residents of lawless north eastern Nigeria, her family lived in constant fear of the terrorist group.

Before they set fire to the school, the Boko Haram fighters looted the storerooms and loaded their trucks with food. Then they ordered the girls to board a large lorry, firing their guns in the air when some of them refused. When the truck was full they ordered the rest of the girls to walk.

"We were all afraid. We didn't know where they were taking us and were talking in a language that we didn't understand. So we were all scared," said Sa'a.

The convoy left Chibok and, after several kilometres, they ordered the girls that had been walking to get into the truck. As it picked up pace, Sa'a noticed that occasionally girls sitting close to the edge were jumping into the undergrowth. She also noticed that the fighters were not stopping to chase them.

"I was sitting in that truck thinking: What are they going to do with us? I thought I would rather jump out the truck and fall down and die. At least [then] my parents will see my body," she said.

Sa'a whispered to her friend that she was going to escape and urged her to follow. Then she stood up and leapt into the thick brush that lined the road. She lay flat on the ground until the lights of the convoy faded. Then she heard her friend screaming for help.

Finding her classmate nearby with a broken ankle, Sa'a had little choice but to spend the night in the forest. The pair sat under a tree and when the sun came up they approached a shepherd, who took them both back into Chibok.

That was the end of Sa'a's experience with Boko Haram – but it is only the beginning of this story.

Mohammed Yusuf was always good at getting headlines. In 2009, the Boko Haram founder told the BBC that the idea that the world was round was contrary to Islamic teachings and rejected the theory of evolution. He opposed so-called Western education (Boko in the native Hauser language), believing it to be Haram, or contrary to Islamic law.

But he did not call his movement Boko Haram.

"It is not the name they gave themselves: they don't actually like it that much," said Andrew Walker, author of Eat the Heart of the Infidel: The Harrowing of Nigeria and the Rise of Boko Haram.

"Western education and the separation from the Sharia [was] the work of the devil in Yusuf's mind, [but] the name came from the people around them, often Christians, who used to say: 'Oh, those Boko Haram people.'

When it was first established in 2002, Boko Haram was only one of a number of radical Salafi groups in northern Nigeria. Yusuf himself began his career as a recruiter for Izala, a mainstream Islamic society that is tolerated by the Nigerian state.

Wikileaks cables revealed that Yusuf had gradually become more radical, breaking away from Izala and forming his own a movement, known locally as Yusufiyya.

In July 2009, the Nigerian security forces confronted a group of Muhammad Yusuf's supporters in the regional capital of Maiduguri as they made their way to a funeral. A government enquiry later revealed the argument began because some of the Islamists were not wearing motorcycle helmets. A melee ensued and the police opened fire, injuring several of the men.

On 26 July, 70 of Yusuf's supporters attacked a police station in Bauchi State and clashes erupted across Borno, Kano and Yobe. Within two days, Nigerian police had Yusuf's home surrounded and, on 30 July, he was arrested after a brief standoff. By the end of that day, Muhammad Yusuf was dead.

The Nigerian authorities said the 39-year-old was shot as he tried to escape, but few believed it.

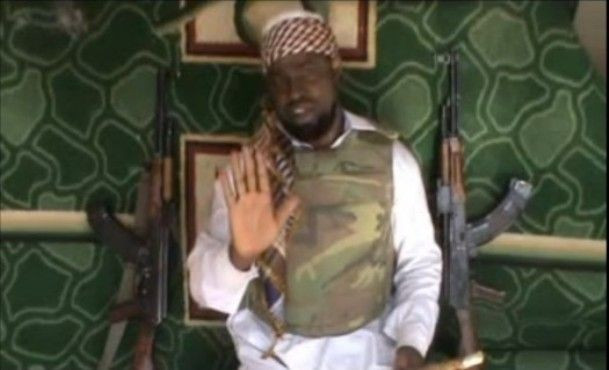

Yusuf's deputy, Abubakar Shekau, was believed to have been killed in clashes with the army during 2009 but in 2010 he appeared in a TV interview with a Nigerian journalist to stake his claim as Yusuf's heir as leader of Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'awati wal-Jihad (People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad) the official name of the group the world knows as Boko Haram.

Teachers who teach western education? We will kill them! We will kill them in front of their students, and tell the students to henceforth study the Qur'an.

It was under Shekau that Boko Haram aligned with al-Qaeda and became the brutal terrorist network they are today. In August 2011, the group bombed the UN headquarters in Abuja, killing 23 and injuring 100, and carried out high profile assassinations of police officers and politicians in the north-east.

In 2012, the group murdered 550 people in 115 attacks, often targeting Christians, and in 2013, Boko Haram supplemented its bombing campaigns with kidnapping, snatching seven French tourists and a priest in neighbouring Cameroon. By May of that year, a state of emergency was underway in Nigeria, covering all three north-eastern states of Borno, Yobe and Adamawa.

As tens of thousands of refugees left northern Nigeria for Chad and Cameroon, reports continued to emerge of endemic police corruption, brutality and extrajudicial killings in north-eastern Nigeria.

While Boko Haram fought with the government police for territory in northern Nigeria, it continued to target schools. In July 2013 militiamen doused a school building in Yobe state in petrol and set it alight, gunning down any students who tried to flee. By the end of the night, 46 people were dead, mostly students.

A month earlier, 16 students had been murdered at schools in Yobe and Borno state. Shekau pledged to target schools "until our last breath". In a video released on the internet, he said: "Teachers who teach Western education? We will kill them! We will kill them in front of their students, and tell the students to henceforth study the Qur'an."

In 2014, a month before the Chibok raid, Boko Haram targeted another boarding school in Borno state, burning classrooms and killing 59 students. Then on April 14, they rolled into Chibok.

Boko Haram were by no means the first African terrorist group to use the mass kidnapping of women as a weapon of war. It was the 1996 kidnap of 139 students from St Mary's College in Aboke, Uganda, that brought the Lord's Resistance Army under cult-like warlord Joseph Kony to international prominence. Kony himself 'married' dozens of the girls and others became sex slaves to his fighters.

But northern Nigeria's tradition of slavery as a weapon of war went far further back. Before independence in 1960, Borno State and the Sultanate of Sokoto controlled half of what is now Yobe, Borno and Adamawa states and would regularly launch raids into each others' territory and seize men, women and children who would either be kept as slaves or sold on.

There is evidence, however, that Boko Haram's kidnap of the Chibok girls was more opportunistic than tactical. Many reports from that night tell of the fighters' surprise not to find any boys at the school.

Equally Boko Haram did not have the space in their trucks to transport all of the girls, as evidenced by Sa'a's account of girls having to walk and later being packed into a single truck. "There was an element of opportunism. They took their time about it," said Walker.

Boko Haram may not prepared for a mass abduction when they arrived at Sa'a's school on April 14, but even after years of bombings, kidnappings and murders, Chibok would be the attack that would define them. Isis would later imitate Chibok in its kidnapping and enslavement of hundreds of Yazidi women as the jihadi group rampaged through Iraq at the end of 2014.

Nigerians marched in the capital, Abuja, immediately after the attacks and on 23 April, 2014, the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls was tweeted for the first time. It would go on to feature in 3.3 million tweets while an image of Michelle Obama holding a piece of paper featuring the hashtag was re-tweeted 57,000 times. As well as protests in Nigeria, thousands took to the streets in London and Los Angeles.

The protests were aimed squarely at the Nigerian state, who had bungled the aftermath of the kidnapping from the very beginning. First it announced that just under 100 girls had been kidnapped, then it claimed that the figure was 129 but that 100 had been rescued. It redacted that statement, and it was left to the parents to reveal that 234 girls were missing.

It later emerged that the military had four hours notice of the attack but did nothing to prevent it – and not for the first time. Boko Haram had been allowed to act with relative impunity in northern Nigeria for years, with regular reports of Nigerian soldiers fleeing their posts rather than engage when they attacked towns and villages. In Abuja, activists within the #BringBackOurGirls campaign had had enough.

Jeff Okoroafor, at the Bring Back Our Girls campaign in Abuja, said that it was the Nigerian state's initial refusal to accept the kidnapping followed by its lacklustre military response that brought Nigerians to the streets. After the first first marches to Abuja's National Assembly, campaigners realised that they needed international attention too. They began approaching celebrities both within and outside the country.

The whole Chibok thing [...] hit a kind of sweet spot. It was the right time to go viral.

Then it snowballed: Barack and Michelle Obama, Malala Yousafzai and then Beyonce, who dedicated a portion of her personal website to the campaign. "From then there was no stopping it," said Okoroafor.

But he did not see the attention to the cause as a surprise: "The fact is that Nigeria had never before has that number of teenage girls been abducted, so it was new to us. The world came to rally around because we shouldn't have to choose between girls having an education and living – because of the importance of that, so I wasn't surprised at all," he said.

On 5 May, Shekau appeared in an official Boko Haram video, taunting the Nigerian government and the world about the Chibok girls. He said that, under Islam, girls can be sold into slavery and that the 16-18 year olds they had kidnapped should be married rather than being in school. Shekau had quickly realised the perverse propaganda that the Chibok abduction provided.

Even for Boko Haram, who are relatively media-savvy for a terrorist movement, the Shekau video was fast. His rhetoric, said Walker, was designed to inflame the situation, to drive fear into Nigerians that Boko Haram was capable of taking the thing they valued most: their children. The video added fuel to the fire, and the #BringBackOurGirls campaign continued to get massive attention across the world.

"The whole Chibok thing [...] hit a kind of sweet spot," Walker said. "It was the right time to go viral."

The support was not only so-called 'clicktivism' either. The US sent army personnel to neighbouring Chad to advise the military effort in northern Nigeria. Britain and Canada also contributed to the search effort. On 17 July, the European Union passed a resolution that called for the immediate release of the girls. But a year later the girls were still missing and the furore died down.

Asked about it now, three years since Chibok, Okoroafor is stoical: "If you look at the world, between then and now, you understand that there are a lot of issues that have been witnessed in most countries – terrorist attacks, global warming, climate change. The world has to deal with those issues," he said.

Their campaign has continued, amassing hundreds of thousands of supporters, but little has really changed for the girls. Around 200 are still in captivity and Boko Haram has published videos showing some of the girls with babies. There has been speculation that some of the girls have been used as suicide bombers and that others do not want to come home after three years in captivity

Sa'a returned home after her escape from Boko Haram but life was not easy in Chibok. The group issued a video statement soon after threatening to find the 50 girls who had got away during the journey on 14 April and to take them and kill their families.

A church group managed to get a US visa for Sa'a and she moved to America to continue her studies. But even in the US, Sa'a uses a fake name and wears dark glasses to conceal her true identity.

Then in October 2016, 21 of the captured girls were released by Boko Haram in a deal brokered by the Swiss government and the Red Cross. When Sa'a heard about the deal, she was excited but equally disappointed that only 21 of her classmates were coming home. When she was shown pictures of the girls, she was shocked by how much they had changed in just two-and-a-half years.

"They looked troubled – traumatised. They looked different from when we were in school. Some of them had babies. I was just sad, thinking about that night. I was like: what if I didn't make that decision that night to jump out of the truck. I might have been one of those girls that came back with babies, or one of those who had died. One of the 195 that are still missing," she said.

But equally it was the sight of the girls returning to Chibok that made her determined to tell her story.

"The day I saw a video of them singing with their parents I was so excited. The smile on their faces gives me hope that one day the rest will come back. It gave me the courage to speak out. I want to be the voice for my missing classmates and tell the world that it really happened," she said.

The fact that they are poor is not a crime.

Back in Abuja, Okoroafor and the Bring Back Our Girls Nigeria team are equally determined to keep the pressure on the Nigerian state, even in the face of pressure by the government and the police to keep quiet. They have been threatened, had their marches blockaded and been regularly smeared over the past three years, but Okoroafor said that the team will not give up until all of the girls are home.

"The government have not been friends to us, but we don't really care. The ball is in their court. We just hope they see the message that we send," he said.

For Okoroafor, it is only because Chibok is a poor town and the Chibok girls not from the political or social elite that their plight was ignored by the Nigerian state. But it is the role of the government, he said, to protect its citizens, regardless of their social standing, their connections or their bank balance.

"They are citizens of this country [and] protection is their right. The government has to do their job," he said. "The fact that they are poor is not a crime."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.