David Cameron's decade: From idyllic English upbringing to Britain's prime minister

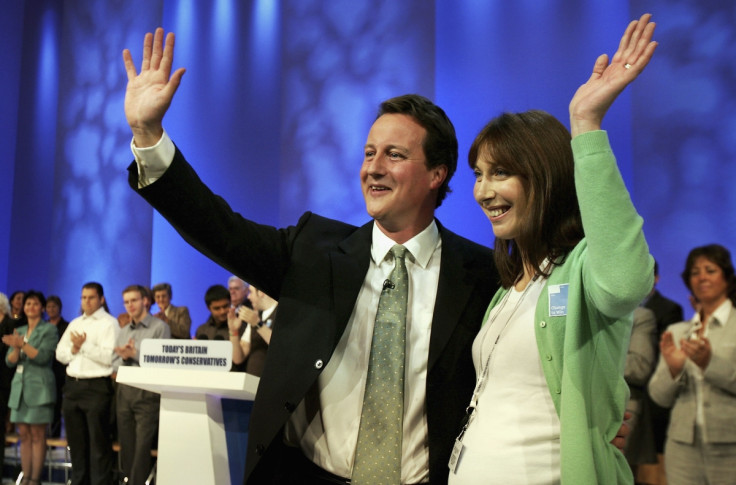

David Cameron will have been at the helm of the Conservative Party for a decade on 6 December, with over five of those years as UK prime minister. In 2005, he fought off the veteran Conservative MP David Davis for the party leadership – and has stayed in charge since.

The 49-year-old was the subject of a lengthy biography called Call Me Dave, researched and written by political journalist Isabel Oakeshott and billionaire Tory donor Lord Ashcroft. It was published after the prime minister secured a shock parliamentary majority at the 2015 general election.

Call Me Dave tells the story of Cameron from birth to Downing Street. As he marks his decade in charge, here are 10 clippings from the biography that help explain his success.

He had an idyllic upbringing by wealthy parents in the Old Rectory, the Camerons' Berkshire family home.

Cameron's upbringing there was quintessentially English, full of fresh air, croquet and homemade cakes. One childhood friend who came from less well-off stock and spent many happy summers lounging by the pool with him and his siblings was mesmerised by the old-fashioned wholesomeness of it all.

"To me it was like a fairy tale; like living in an Enid Blyton book. His mother would come out to the pool with jugs of homemade lemonade and freshly made cakes. It was just idyllic, the house was absolutely gorgeous, and they were very privileged – but very nice.

"The pool was a focal point of the kids' life. We just hung out there... Dave was a very good swimmer and I remember him diving. We spent time in the kitchen and of course there was an Aga and all that posh stuff. We played board games and cards by the pool. I don't remember watching TV; it wasn't that kind of era. We amused ourselves; I remember going on walks in the countryside and cycling, and going to the local shop for sweets."

He attended Heatherdown, where Prince Andrew and Prince Edward were pupils, then the exclusive Eton College for his schooling.

At a time when air travel and foreign holidays were beyond the reach of most ordinary people, pupils at Heatherdown enjoyed ski trips and African safaris. Every year, the headmaster would take a party of boys to Switzerland, Austria or the French Alps, accompanied by one or two younger masters to keep them in order.

As a young teenager, Cameron was indeed remarkably sophisticated. While other boys his age were preoccupied with their sporting achievements, his godfather Ben Glazebrook recalls him nonchalantly proffering dining recommendations.

"We had this party with some of our godchildren and David's 15 or 16-year-old friends from Eton. They were all talking about getting their cricket colours. David was obviously very bored by this, and said: 'Do you know the Etoile restaurant in Soho, Ben?' He knew the menu by heart. 'The sole Monégasque is so delicious,' he said. The other boys' jaws were dropping. He was far, far more sophisticated than his contemporaries."

He has always had a network of family friends in the establishment who could put in a friendly call to open doors.

After graduating with a first in PPE from Brasenose College at the University of Oxford, Cameron...

...had sauntered into a plum job in an elite department of the Conservative Party. Exactly who helped Cameron get this job and how is a matter of debate. Until now, attention has focused on a mysterious phone call, purporting to be from the royal household. However, he may also have been helped by a second source. The anonymous phone call went through to Alistair Cooke, now Lord Lexden, then deputy director of the Research Department, shortly before Cameron's first interview.

The caller, who had a grand voice, told Cooke to stand by for someone special. 'I understand that you are about to see David Cameron. I've tried everything I can to dissuade him from wasting his time on politics, but I have failed. I am ringing to tell you that you are about to meet a truly remarkable young man,' he said, and hung up.

Cameron has always had political canny and been willing to play the game.

After Margaret Thatcher's resignation in 1990, three Tory MPs started their leadership bids: Michael Heseltine, Douglas Hurd and John Major. At the time, were three prominent backroom Conservative staffers – Ed Vaizey, Ed Llewellyn and David Cameron – who were restricted to political neutrality by the party's rules for those working at CCHQ.

Holed up just off Smith Square in the Gayfere Street home of Alan Duncan (soon to become an MP), John Major's campaign team was cheered to receive a visit from Ed Vaizey. 'Sorry I can't do anything to help now, but I just wanted to let you know I'm supporting you,' he told them cheerfully, adding that he would make himself available that weekend. A number of other Central Office staff dropped by, including Cameron and Llewellyn, who turned up together. Like Vaizey, they offered warm words of support and made noises about pitching in as soon as they could.

That weekend, Vaizey turned up at Major's campaign headquarters as promised, but there was no show from Cameron or Llewellyn. Long after it was all over, Major's supporters discovered that the pair had delivered the exact same warm words of support to Michael Heseltine and Douglas Hurd, leaving all three contenders under the happy illusion that they enjoyed the support of two of the party's bright Young Turks. Smart, fly, or both?

When he wants to be, Cameron is ruthless.

...in their determination to shed the vestiges of its image as the 'nasty party', as Theresa May had provocatively put it, the new leadership took few prisoners. An early victim was Cameron's shadow Homeland Security Minister Patrick Mercer, who was ruthlessly culled for telling a journalist he had met 'a lot' of 'idle and useless' ethnic minority soldiers who used racism as a 'cover'.

The former army colonel also told The Times that being called a 'black bastard' was a normal part of army life. Mercer was not condoning the use of such language, and his remark about workshy ethnic minorities sounded far less offensive in the context of the wider interview. However, Cameron threw him to the wolves, telling Mercer in an exchange that lasted less than 60 seconds, 'You're relieved of your command, Colonel.'

Cameron has always had close groups of powerful, rich and well-connected friends.

For some, the 'set' is evidence of a deep-rooted cliqueyness in Cameron's character. He went from the Bullingdon Club to the Brat Pack – also known as the 'Smith Square set' – straight into the 'Notting Hill set' and, later, the 'Chipping Norton set'. He is nothing if not clubbable.

The death of his much-loved and severely disabled son Ivan, aged just six, changed Cameron profoundly.

A number of those who know and admire the prime minister argue that Ivan changed him for the better. A former aide says: 'I remember talking about this with Lord Chadlington. He said Cameron had had everything given to him in his life. What changed him was the birth of Ivan. Having a son who wasn't perfect, wasn't normal, really affected him and changed him for the better. I agree with that thesis. My impression of Cameron before Ivan was that he was a snobby little snot.'

Another former colleague believes he 'became a different human being' thanks to his son. 'He became aware that with all the advantages he'd had in life, there are things you can't change. I think it did give him a different perspective. The first impression you had of him as a 24-year-old was, 'Oh my God, what a frightful, braying Tory.' I think he became much less of a frightful, braying Tory over the years.'

He is a moderniser who dragged the Conservatives into the 21st century and tried to shake off its "nasty party" reputation.

The expedition that became known as 'the husky trip' symbolised the dramatic change under way in the Tory Party. Traditionally, it had had little truck with touchy-feely issues like the environment. Indeed, the party harboured many climate change sceptics. Now Cameron was applying for planning permission for solar panels and a wind turbine on his own roof and asking people to 'vote blue, go green'.

Cameron is relentlessly loyal to those in his inner circle.

An example is the generosity he showed Hugo Swire, one of his best friends at Westminster. In 2007, he was forced to sack Swire as shadow Culture Secretary after Swire suggested the Tories would scrap free museum entry. Unusually, however, he gave Swire a second chance, offering him a ministerial post in Northern Ireland in 2010. He told a colleague that Swire was 'a very good friend' and that it was 'very important' that he 'succeeds and is seen to succeed'.

Above all, he is very, very lucky – though he has used his luck well.

To some, including his old friend Derek Laud, Cameron is simply 'lucky, lucky, lucky'. There is some truth in this. He would be the first to acknowledge – and indeed has said himself – that he has been blessed with immense good fortune. He was lucky in his upbringing, his family's wealth, his education, his talent, his temperament and his connections.

Though he was eminently qualified for the string of desirable jobs he landed in his twenties, success came naturally to him and he did not become used to fighting for advancement. He never had to try too hard. Once in Parliament, he was lucky in the circle of friends and advisers who surrounded him, and the qualities they brought to bear: the drive and creative genius of Steve Hilton, the political judgment of George Osborne, the financial backing of Andrew Feldman, and the intellectual and practical contributions of figures like Andrew Cooper and Daniel Finkelstein. Without them, it is unlikely he would have become leader in the first place.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.