Dutch election 2017: Will Holland follow Britain and America in a vote for right-wing populism?

Britain backed Brexit and the US voted Donald Trump - Geert Wilders hopes the Netherlands will mirror trend.

What was supposed to be a march comprising around 50 protesters with a megaphone turned into a 3,000-strong rally against President Donald Trump's Muslim travel ban in the Dutch capital of The Hague.

While the rally was manifestly against Trump's policy, under the banner: 'Holland against hate,' some of the more progressive political parties in the country also took part in the demonstration - including deputy prime minister and Dutch Labour party (PvdA) leader Lodewijk Asscher.

According to rally organiser Wouter Booij, the anti-Trump protest was primarily for equality and inclusion. For many, it may have offered the chance to consider how these issues were playing out in the Netherlands, too.

"Those people aren't just there because of Trump. Many people in this country are thinking, there are other parties that may implement similar policies here too," he told IBTimes UK. "It was a wake-up call. We have a progressive majority in this country that was silent for a while but now they see they need to stand up," he added.

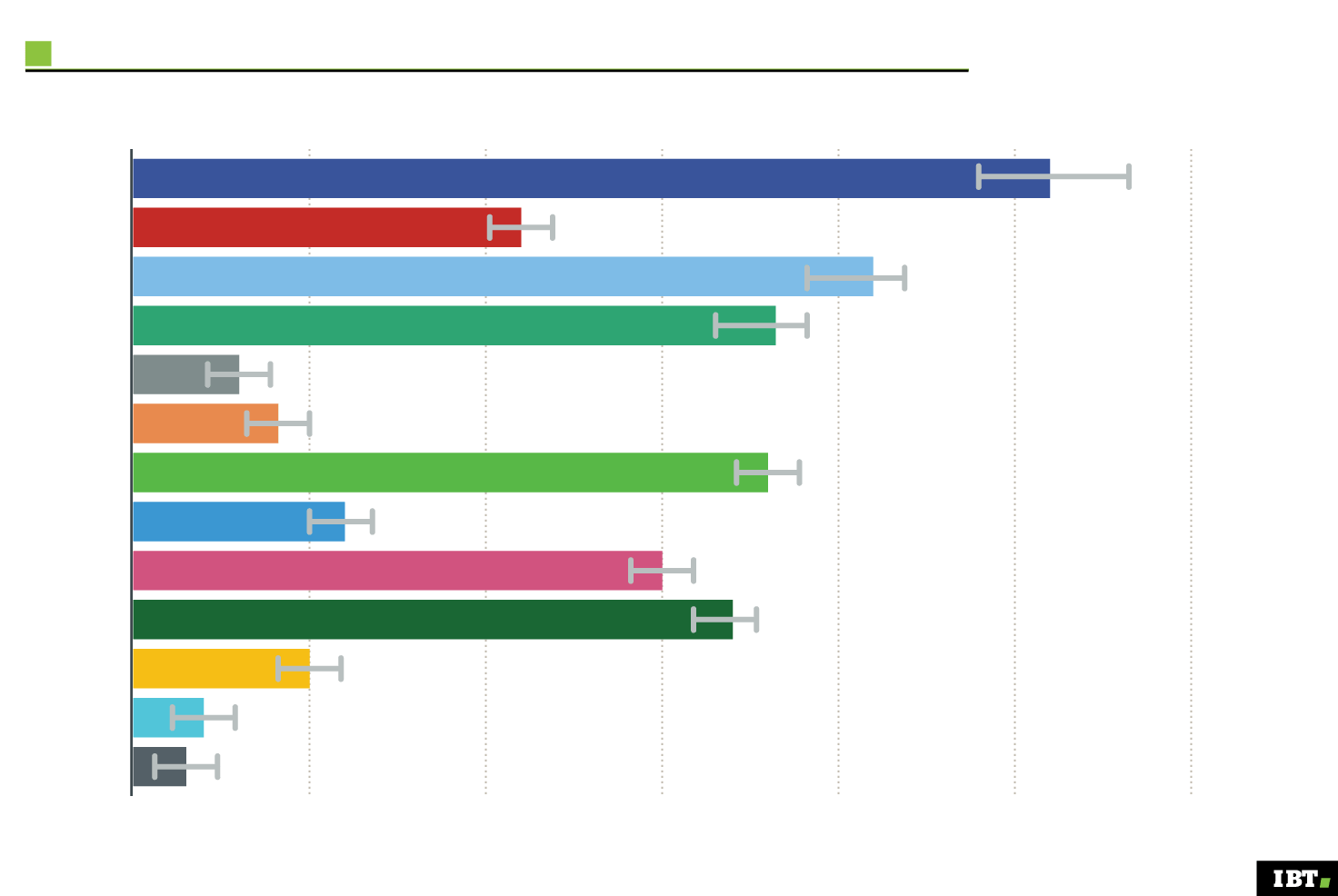

The timing could not have been more significant, as around 13m Dutch voters go to the polling stations in less than six weeks, on 15 March, to vote for the House of Representatives. The latest polls, published on 2 February by Ipsos and reported below in a graph, show that the anti-immigrant, populist Freedom Party (PVV) may win a majority of the vote.

Party leader Geert Wilders, who is recently being dubbed the 'Dutch Donald Trump' in the international press despite having been in politics for over a decade, has praised the policies of the newly-elected US president and actually encouraged him to expand the travel ban to Saudi Arabia.

Can Wilders win?

Wilders created the PVV in 2006, after he broke off from the centre-right People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD). His party's popularity has been fluctuating in the past decade. In the first election contested in 2006, the party won 9 seats. In 2010, they won 24 seats and propped up the minority government led by VVD leader Mark Rutte. Wilders was also responsible for the collapse of that government in 2012, due to different views over budget cuts and his party lost support in the elections, losing 9 seats.

This time around, Wilders' party is projected to win more seats than ever - 28, according to the Ipsos poll. There are precedents for polls overestimating the support of a radical party ahead of the election: ahead of the 2012 election, the Socialist Party (SP) was predicted to win more than 20 seats, although it only won 15.

Should Wilders actually win a majority of the vote in March, his chances of becoming prime minister are not immediately assured. While the Netherlands is similar to the United Kingdom in being a parliamentary monarchy, the party system is much more diverse and polarised than in Britain, with the composition of the Houses of Parliament reflecting that diversity.

The Dutch Parliament

The legislative body is divided in two chambers, a lower house (Tweede Kamer in Dutch) and the upper house (Eerse Kamer in Dutch). The March election only concerns the Lower House. The upper house of parliament is made up of 75 senators, who are elected according to a different schedule from the lower house. The most recent Senate elections were held in 2015, and the VVD party holds a majority of 13 seats, followed by the Christian-democrat CDA (12) and the centre-right D66 (10). Politically less significant than the House of Representatives, the Senate has the right to accept or reject legislative proposals but not to amend them or to initiate legislation.

There are currently 11 parties represented in the 150-seat house of representatives, plus 8 lawmakers acting as independents. The voting system is one of proportional representation, with a number of seats redistributed among the biggest parties once all the other seats have been allocated according to the percentage of the vote won, rounded down.

It is very unlikely for any one party in the Netherlands to get more than 30% of the vote and rule by itself, as most governments are formed by a coalition of parties. The record 31 parties participating in the upcoming election will ensure an even higher fragmentation of the vote.

As the polls stand this week, it would take at least three parties to join forces to attain a majority in parliament and Wilders' divisive policies on immigration, freedom of religion and international cooperation (including the Netherlands' membership of the European Union) may hurt his chances in finding other like-minded allies with whom to govern.

Incumbent prime minister Mark Rutte has already categorically excluded the possibility of governing with Wilders, yet he has publicly taken a harder stance against foreigners in a bid to appeal to those who may consider voting for his rival. In doing so, Rutte risks alienating some other voters who would consider supporting his VVD party and, in fact, he lost support in the latest polls compared to 19 January, before he made the controversial statements.

Support for each party and projected seats

Final polls ahead of 15 March election place VVD in the lead.

VVD

PvdA

PVV

CDA

SGP

50plus

D66

CU

SP

GL

PvdD

Denk

Others

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Source: Peilingwijzer.tomlouwerse.nl

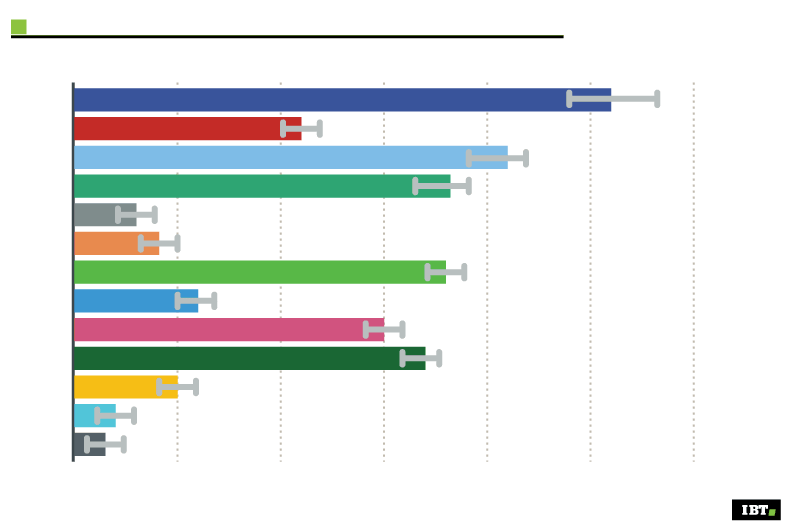

Support for each party and projected seats

Final polls ahead of 15 March election place VVD in the lead.

VVD

PvdA

PVV

CDA

SGP

50plus

D66

CU

SP

GL

PvdD

Denk

Others

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Source: Peilingwijzer.tomlouwerse.nl

With more than a month to go and millions of voters still undecided, a lot can still change. One thing that seems highly unlikely is a centre-left government taking power. The centre-left PvdA is suffering in the polls, which project a loss of more than half of the party's current 38 seats - a possible sign of dissatisfaction with the policies the party supported in the coalition government. Some of the votes seem to have gone to the more left-wing environmental party Groenlinks (GL), the Christian-Democrat party CDA and to the centre-right progressive D66 - all three parties are predicted to gain seats in the March vote, as shown in the graph above.

Some of the electorate may have been turned off by the political scene altogether and may not bother voting. One of the parties competing in the election is catering specifically to their needs: the Non-voters Party, led by criminal defence lawyer Peter Plasman, underscores a growing discontent with a political system that aims for agreement and compromise.

It is that portion of Dutch society that Booij hopes to mobilise and woo with the Holland against Hate movement. "There is a progressive majority in this country, even bigger than we see now. I truly believe that a lot of people who may not have voted before are going to vote in this election for the first time." he said. "We may have woken up everybody a bit, or at least Trump did."

The Dutch population in 2016

With immigration and asylum policies expected to take centre stage in the debates leading to the election, here are some numbers about the country's population breakdown. It is worth noting that the Dutch bureau of statistics CBS, from which this data is taken, already offer a breakdown of the immigrant population in "western" and "non-western" categories. In Dutch, the word "allochtonen", meaning "coming from a different land" is used to refer to 1st and 2nd generation immigrants in contrast with "autochtonen", meaning "natives".

Total population: 16,979,120

Men: 8,417,135

Women: 8,561,985

Non-immigrant population in 2016

13,226,829

Immigrant population in 2016 (1st & 2nd generation)

3,752,291 (22% of total population)

Breakdown of immigrant population

Western countries: 1,655,699

Non-western countries: 2,096,592

- Morocco: 385,761

- Dutch Antilles & Aruba: 150,981

- Suriname: 349,022

- Turkey: 397,471

- Other non-western countries: 813,357

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.