Interview with Eben Upton - Raspberry Pi Founder

Eben Upton, founder of Raspberry Pi speaks to the International Business Times UK about the £22 computer which could revolutionise how students are taught about computers in schools.

At one stage last week, more people in were searching Google for information about a £22 credit card-sized computer which doesn't even have a case than were searching for information about Lady Gaga.

The Raspberry Pi computer has captured the imagination of a lot of people around the world, even people who normally would have no interest in computing - and that is exactly the point.

Speaking to us from his skiing trip in the States, the man behind the Raspberry Pi said it was the fall off in standards he witnesses as a lecturer at Cambridge University which was the spark for this whole project:

"I was getting really pretty concerned. I was interviewing people to come to Cambridge and I'd had a particular expectation set in my mind from what I remembered from when I was an undergraduate and then seeing the number of people applying, the reduced number of people and the very basic stuff we had to teach them in the first year in order to bring people up to the bar was kind of disturbing."

Upton believes that the dotcom boom of the mid-to-late 1990s also had the effect of masking the reality of the decline in interest in basic computer skills:

"What we actually think had happened was there had been a fall-off in the underlying numbers from the mid-90s but the dotcom boom had masked that because a lot of people had started applying because they thought computer science was a meal ticket. And so it had hidden the true decline, so once the dot com thing went away suddenly you saw a steeper decline and the underlying numbers became visible to us."

The 'us' Upton is talking about was a group of like-minded colleagues at Cambridge University who decided to do something about this issue and set about designing a cheap, reliable and basic computer which could be bought by educational institutes from secondary schools upwards to help get students' IT skills back up to scratch.

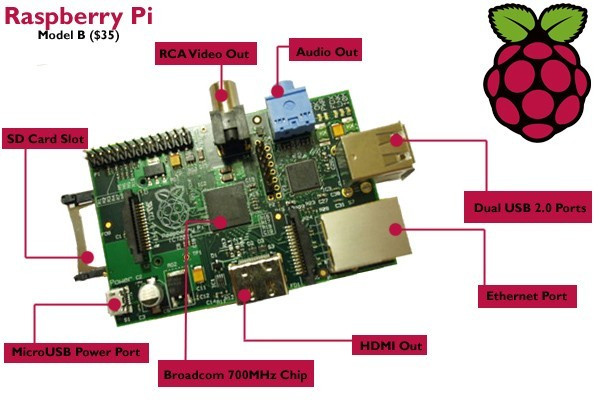

The result is the Raspberry Pi which is a credit card-sized computer featuring an ARM-based Broadcom System-on-Chip (SoC), USB ports, HDMI port, SD card slot and, on the higher-spec model, an Ethernet port. The first model rolled off the production line only a couple of weeks ago and on the morning the first batch - which are primarily aimed at developers - went on sale, the two companies distributing them were receiving around 700 requests a second for the Raspberry Pi.

"The level of interest across every mainstream media outlet in the UK and quite a lot worldwide, was a big surprise to me," Upton said.

While the company has hit a minor manufacturing hiccup due to an incorrect component being fitted in the factory in China, Upton believes the Raspberry Pi Foundation, which is the organisation set up to oversee the design, manufacture and distribution of these computers, will be able to ramp up the volume of production without much of a problem.

"We have ensured we can get them in large numbers and Premier Farnell and RS Components [the two distributors] have been fantastic at helping to source components," Upton said.

Upton himself works for Broadcom during the day, which certainly helped when trying to secure the correct SoC for the Raspberry Pi. Broadcom chips are based on the low-power architecture from ARM, which is a British-based company. With the decline in the standard of basic computing skills at university level, we wondered if Upton thought this could spell the end of such British-based tech companies:

"I think that is a threat. ARM is an amazing British success story and out of really humble origins they have come to be cause a lot of trouble of Intel at the moment. If we want to do another generation of companies like that it is going to prove very difficult to find the best, efficient supply of engineers to staff them."

The Raspberry Pi's real coup was managing to combine hardware components which are "cheap, reliable and available" which is all thanks to one man, Pete Lomas, who Upton calls the Steve Wozniak of Raspberry Pi. However UIpton is at pains to point out he is not the Steve Jobs of the company:

"Pete Lomas, who did all the hardware design, he's like our Steve Wozniak. We're a company with a Wozniak but no Jobs."

The initial round of Raspberry Pi boards, which will ship without cases, will mostly find their way to developers who will develop software applications for the Linux-based computer. The second batch of computers, which should feature a case will be aimed at educational institutes and should launch in three to four months, according to Upton. But has he been happy with the reaction from these institutes?

"On an individual level, yeah. A lot of individual teachers, a lot of individual universities have been very receptive to the idea and I think that is probably enough [initially]. I think it is going to be an effort if we want to get the stuff into the curriculum then that is obviously an order of magnitude more complicated meaning a lot of government interaction."

There has also been a lot of interest from outside the UK, including "a lot of interest in both the developed and developing world" The Raspberry Pi Foundation has been clear that it is not precious about the platform it has developed and would welcome other manufacturers to come along and replicate what it has done. Upton believes that the micro-computer can be a commercial product and that in the future this is the way computing will go:

"I think in five years time, regardless of if people are doing it in an open way or whether they are doing it for educational [purposes] or if they are looking to make appliance-locked devices and displace the PC that way, I think we are going to see a lot more Raspberry Pi-like devices."

The reason Upton thinks this is that he cannot see the current system of hugely expensive computers continuing to sell in large numbers, now that the Raspberry Pi has shown it can be done:

"My feeling is that this device is a harbinger of the way things are going to be in the future. You look at the current cost of computing and you look at what you can get in the way of a cheap ARM-based SoC for $10-$20 and you think why do computers cost hundreds of pounds and why are they so big and why do they consume so much power?"

But what about a Raspberry Pi Mark II? While Upton was at pains not to talk about any specific future product that may or may not be in the pipeline, he did say it is something being considered:

"I think we'd like to keep doing Raspberry Pis. I think we are good at them. The current device is very strong at some things, it is strong in graphics, it is strong in video. It is not an especially powerful processor. It is enough but not too much. If we could, we'd love to figure out a way to build a version that has the same amount of graphics but has more general purpose computing heft."

With the Raspberry Pi grabbing the imagination of the public, could we be getting ready to see a computing revolution and seeing students return to programming and learning basic computer skills which seem to have been lost as computers, smartphones and tablets become ever more user friendly? Only time will tell.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.