EmDrive: British scientist's 'new physics' theory accidentally proves controversial space propulsion works

British physicist Dr Mike McCulloch of Plymouth University has presented results on a new theory.

British physicist Dr Mike McCulloch of Plymouth University has presented predicted results on a new theory of inertia that match the order of magnitude of thrust on all experiments done so far on the controversial electromagnetic space propulsion technology EmDrive.

McCulloch's research involves violating Einstein's Equivalence principle by stating that there is a new acceleration extracted from the zero-point field by horizons, and that if inertia were to be quantised at small accelerations, this would explain the anomalous thrust produced by the EmDrive.

British scientist Roger Shawyer devised the EmDrive concept and first presented it in 1999, but spent years having his technology ridiculed by the international space science research community. According to Shawyer, if the technology is ever commercially realised, EmDrive could transform the aerospace industry and potentially solve the energy crisis, climate change, and speed up space travel by making it much cheaper to launch satellites and spacecraft into orbit.

Yet despite the controversy attached to the technology, since 2012 eight independent studies have been carried out by scientists from China, Germany and even Nasa to try to build and test their own versions of the EmDrive, and although the researchers are not sure why, they have all discovered signals of thrust that cannot be explained.

If McCulloch's theory about inertia, explained in the paper "Testing quantised inertia on the emdrive" (published on Cornell University Library's open source database) is proven to have validity, then this would be the first viable explanation for how exactly the EmDrive is able to work, when theoretically it shouldn't be possible.

What is quantised inertia?

How the EmDrive works

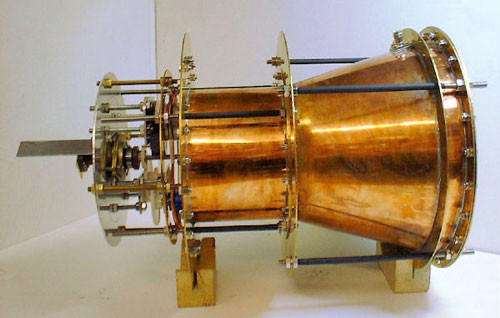

The EmDrive is the invention of British scientist Roger Shawyer, who proposed in 1999 that based on the theory of special relativity, electricity converted into microwaves and fired within a closed cone-shaped cavity causes the microwave particles to exert more force on the flat surface at the large end of the cone (i.e. there is less combined particle momentum at the narrow end due to a reduction in group particle velocity), thereby generating thrust.

His critics say that according to the law of conservation of momentum, his theory cannot work as in order for a thruster to gain momentum in one direction, a propellant must be expelled in the opposite direction, and the EmDrive is a closed system.

However, Shawyer claims that following fundamental physics involving the theory of special relativity, the EmDrive does in fact preserve the law of conservation of momentum and energy.

In December 1990, as the Galileo spacecraft flew past Earth on its way to Jupiter, the spacecraft's speed suddenly jumped by 4mm/s. Then in January 1998, Nasa's Near spacecraft suddenly saw its speed jump by 13mm/s as it swung past Earth. The same phenomena were also seen in 1999 when the Cassini spacecraft's speed jumped by 0.11mm/s, and again in 2005 when the Rosetta spacecraft jumped by 2mm/s while flying by Earth.

These incidents are known as "flyby anomalies" and no one knows why they occur. McCulloch has been studying the phenomena since 2006 (read his blog here), developing a theory about horizons and their effect on dynamics.

The Hubble Horizon is a conceptual horizon defining the boundary between particles that are moving slower and faster than the speed of light relative to an observer at one given time. In 2007, McCulloch published a paper explaining that the only Unruh radiation waves (an effect predicted by general relativity) to cause inertia are damped by the Hubble Horizon, which is very far away on the other side of the universe (10<sup>26m away). In order to be damped by this horizon, the wave has to be the same size and to get Unruh waves at that size, the acceleration has to be incredibly small.

Einstein's Equivalence principle theorises that if you were to drop a heavy ball and a lighter ball off a tower, they would hit the ground at the same time because although the heavier ball has a greater gravitational mass, it also has a greater inertial mass, so the time to the ground is the same.

"My theory is saying that the inertial mass is different to gravitational mass but in a way that doesn't depend on the mass, and the difference is so small it cannot usually be detected. What I'm saying is that there's an extra acceleration from the Hubble Horizon that applies to everything equally – it's very small, just 6.7x10 <sup>-10m/s<sup>2," McCulloch told IBTimes UK.

But since 2014, he has expanded his theory and applied it to light, and now he is theorising that photons (i.e. light) have inertial mass, and that if they have an inertial mass, they must experience inertia when they reflect, even if it is too small to be detected.

"It's very controversial, whether light has inertial mass or not. The problem with assuming that photons have inertial mass, is that if they do have that, then standard physics cannot explain why they're going at the speed of light. I'm saying that it's a new force extracted from the zero-point field by horizons that makes it possible," explained McCulloch.

How does this theory apply to EmDrive research?

To test out his theory, McCulloch has been using it to predict the forces that must be generated and he has systematically worked his way through 29 different anomalies, and now he has tried his model out on the EmDrive.

"I predicted in my latest paper that if you arranged the shape of the EmDrive so that the wavelengths of the Unruh radiation waves being seen in the cavity fit better into the narrow end than the wide end, then the thrust should reverse," he said.

"I looked at eight experiments (including two by Shawyer and four by Nasa Eagleworks) and the predicted results seem to agree, but I don't know what the uncertainty of the error bar on the experiments is."

Because there is as yet no convincing explanation as to why EmDrive works, many scientists and engineers continue to be skeptical that it can really work, despite Shawyer's assertion that the private space industry is already developing the technology for commercial use, so McCulloch's theory could help to validate EmDrive.

However, McCulloch has faced his own critics due to his assertion that light has inertial mass, and for the assertion that the speed of light must change within the truncated cone cavity.

And while he respects Shawyer for his invention and believes that ultra-fast propellant-less space travel will one day be possible, like many scientists McCulloch does not agree that Shawyer understands the real reason why EmDrive works.

"He is using special relativity but he's claiming a violation of the conservation of momentum. In order to do that, you really do need new physics, which is what I'm suggesting. He's suggesting there's nothing new under the sun, that this can be allowed. I don't accept that. Conservation of momentum has been very well tested and it should apply to special relativity as well," he stressed.

"In order to extract the energy required to do this, it has to be new energy and it has to come from somewhere, and I'm saying it's coming from information, which is a very new kind of physics. I've found I can get my theory to work by assuming that what is conserved is not mass and energy, but mass, energy and information stored on horizons."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.