EU referendum: Need proof that immigration is good for the UK economy? Just show this graph

Amid all the photos and video clips on my mobile phone, I keep a graph that shows some rather stark economic data. The diagram stays close to me at all times so it can be unfurled whenever I'm embroiled in an argument about immigration. Unfortunately this is happening with depressing frequency during the current EU referendum campaign.

I use the graph because – more so than any words I could possibly utter – it succeeds in stopping even the most virulently anti-immigration Brexiteer in their tracks.

While it's not quite a definitive argument clincher, it makes everyone who sees it at least question their previously unshakeable belief that Britain will be a better place if immigration is drastically reduced.

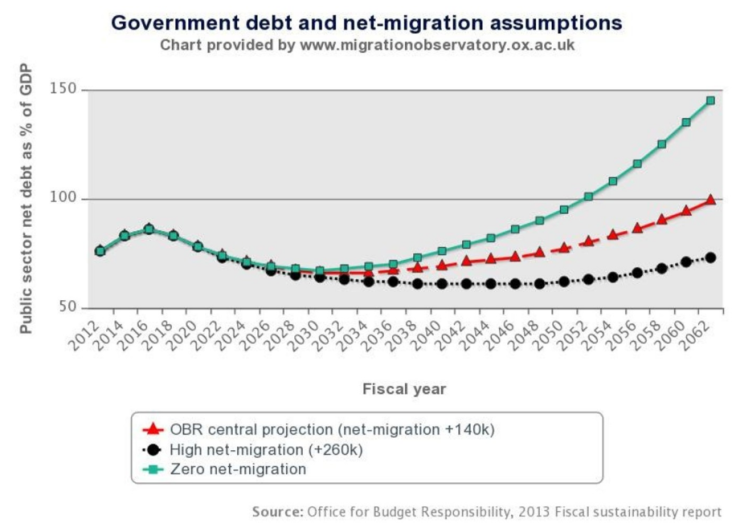

Produced by the official independent fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), it forecasts what will happen to the UK's national debt under different migration scenarios.

As the graph demonstrates in arrestingly clear terms, little or no immigration means hugely rising national debt over the coming decades. A medium level of immigration means a reduced burden of debt, and high net immigration at or above 260,000 people a year means that, all other things being equal, national debt can be kept at a stable level.

To put these figures in context, Britain's annual net immigration has consistently been above 200,000 for the past decade and rose above 300,000 in the last couple of years.

The reasons for this analysis from the OBR are obvious. Like all advanced Western nations, Britain has an ageing population and, as things stand, we cannot afford to pay for the resultant pension and healthcare costs.

The ideal demographic distribution, like in the classic 'population pyramids' studied in school geography lessons, is a large amount of working age adults in the middle to support a relatively small number of pensioners at the top, and then an even larger number of children at the bottom coming through as future workers.

But the reality of the 21st century advanced nations is becoming more like a rectangle than a pyramid. There are now almost as many pensioners at the top as there are workers in the middle and children at the bottom.

Which is where immigrants come in. The vast majority are of working age, and will undertake the labour and pay the extra taxes needed to fund the costs to the state of an elderly population. Not only that, but their wider contribution to the economy helps generate extra growth that raises tax revenues from the rest of the population. To top it off, they also tend to have a higher birth rate – which means more young workers in the future.

The analysis is a very simple one, and there are some experts who will disagree with it. But the pertinent point is that this is the scenario sketched out by the organisation the government relies on to provide independent and authoritative analysis of the UK's public finances.

When ministers measure the financial implications of their policies, they do so using figures provided by the OBR. And this particular view of the relationship between immigration levels and national debt is one echoed by similar bodies advising governments across the world.

That is why the Tories have made no concerted effort at all in the last six years to achieve their manifesto aim of reducing net migration to 'tens of thousands' a year. According to several reports, figures like the Home Secretary Theresa May have wanted to adopt a far more hardline approach on migration but they have been smacked down by the cold, hard financial reality espoused by Chancellor George Osborne.

The OBR's analysis explains why the last Labour government was so eager to open up Britain's doors to a large immigrant workforce from Eastern Europe and elsewhere. Tony Blair, Gordon Brown et al were acutely aware of the looming time bomb that had been ignored for too long.

If anyone wants to understand why advanced nations with high immigration like the UK, US and Australia have emerged so robustly from the 2008 economic crash – while zero-immigration Japan has been mired in stagnant growth for two decades – they will find their answer in the OBR's diagram.

It also explains why Angela Merkel was so keen to accept a million refugees into Germany last year. It was less a humanitarian gesture than a deliberate policy to safeguard Germany's immediate fiscal future.

In the specific context of the EU referendum debate, the OBR analysis was backed up by a report two weeks ago from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR). The think tank said that a reduction in EU immigration as a result of Brexit would have a 'negative impact on the public finances' which might have to be offset by 'increases in national insurance contributions, reductions in pensioner benefits or increases in the state pension age'.

It would be interesting to know how many Brexiteers would be happy to swallow all or indeed any of these bitter pills.

To be fair, the NIESR did suggest these effects could be mitigated by using a points-based system to ensure only the most productive immigrants arrive in the country. But the most commonly cited example of such a system – the one in Australia – actually lets in almost three times as many immigrants per head of population as come into Britain. Indeed, the NIESR itself questions 'whether these policies would and could actually be delivered in practice'.

So in the absence of any obvious remedy that has been shown to work elsewhere, we are still left with the quandary of how to severely restrict immigration without punching a huge black hole in the nation's finances. But that is not to say Britain should have uncontrolled immigration. Far from it.

The influx of foreigners undoubtedly causes a strain on public services and housing, as well as raising concerns over the dilution of whatever national culture Britons still share in common. No-one is oblivious to these issues

The influx of foreigners undoubtedly causes a strain on public services and housing, as well as raising concerns over the dilution of whatever national culture Britons still share in common. No-one is oblivious to these issues, and serious thought has to be put into how immigration is managed and controlled.

There is also the very obvious point that while new immigrant workers may help fund the living costs of today's pensioners, they in turn will become older and less productive as the years go by.

But there is a school of thought that, even if this happens, they will not prove to be such a cost to the UK state. This is because many traditional immigrant communities have a culture of looking after their elders in the family home, while the evidence from the first generation of Commonwealth immigrants suggests that a fair number prefer to retire back to their country of origin – at least over the winter – rather than remaining in Britain.

Perhaps it is fair to say that ministers may have their head in the sand over this issue. They know they can buttress the public finances in the short-term by allowing relatively high levels of immigration, and they will leave for future administrations the problem of what to do when these immigrants become pensioners.

They do this because it is simply too daunting and too taxing to face the alternative. An immigration policy that only lets 'tens of thousands' of people into Britain every year will, eventually, lead to financial oblivion.

Anyone who seriously wants immigration cut to this level, or even lower, needs to take a long, hard look at the OBR graph and explain which taxes they would impose or which chunks of public spending they would keep on cutting every single year for the next few decades to ensure an outcome more like the black line than the green one.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.