The Eurozone - A Crisis of Confidence

Reading Bloomberg News' article by Lorenzo Totaro at lunchtime, Friday 28 October on Italy's latest Bond Sale falling short of expectations and the country's borrowing costs rising, I quickly checked to see what its current National Debt is. At €1,900.8 billion, amounting to €31,500 per inhabitant, this roughly measures 120 per cent of Italy's GDP.

For as long as I can remember, I had on occasion read articles in The Economist or Financial Times reporting on the very high Italian National Debt to GDP ratio which often exceeded 100 per cent. Until the creation of the Euro, any problem that this might give rise to was simply the concern of the Bank of Italy and reflected in the exchange rate of the Lira and Central Bank interest rates.

The ratio of national debt to GDP of any member country of the Eurozone soon became ignored, or at least submerged, soon after the Euro became comfortably established and exchanged as an International Currency. There is little doubt that this was a reflection of the fiscal standing of Germany in particular and its partnership with France since the founding of the Common Market.

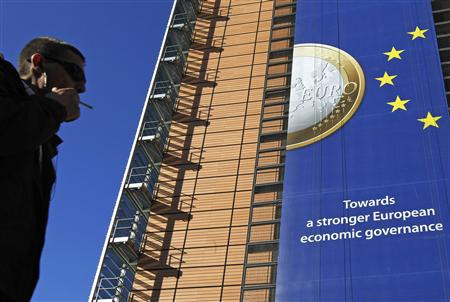

The location of the European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt was also a shrewd choice that inspired confidence, being the home of that stalwart of economic discipline, the Bundesbank. Sadly, we now know, too much dipped below the radar and structures which should have been put into place to support and govern the single currency fell short of what was necessary.

Although never quite the serious challenger to the Dollar its proponents aspired it should be, the Euro nonetheless has become a world Reserve Currency. A natural outcome of being in daily use by over 330 million Europeans one might argue, it is also reflected in its weighted component value of the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) unit of 37.4 per cent (2011-2015), having risen from 32 per cent in 2002. In comparison, Sterling has a weighted value of 11.3 per cent, much the same since the circulation of Euro currency notes.

Perceived from the likes of the US Federal Reserve, the Euro's importance looms even larger. The Euro's measure in the US Dollar Index (USDX) - a basket of six currencies - is a weighted 58.6 per cent. Sterling comes a close third at 11.9 per cent weight, just behind the Yen at 12.6 per cent

The sovereign debt crisis which formerly, largely revolved around Greece, has since developed into a full-blown meltdown of confidence in the political leaders of the Eurozone in particular, and EU in general, to take the necessary steps to resolve the sovereign debt issue and related matters. Such irresolution could yet destabilize the world's trade and exchange rate mechanisms. The world doesn't deserve this and as can be seen from the above statistics, the demise of the Euro would make any Greek default but a trifle.

A list of the 17 countries in the Eurozone and the briefest of studies of their recent economic past quickly leads one to deduce that a number of members should never have joined or been invited to do so. That entry became a political statement of how "good a European" a potential aspirant was is now, belatedly, being acknowledged within the EU's core members as the Euro's single biggest flaw.

But what's done is done and the Markets, whilst accepting that structural changes to the institutional set up governing the ECB and Euro will take time, are not satisfied on the immediate matter of sovereign default. This latest, but unlikely to be last, "comprehensive package" calls for - more like, demands - "voluntary" haircuts of 50 per cent to be taken by Greek bond holders.

Surely a default by any other name! The sweetener is that the new bond issue will come with guarantees. There is to be a recapitalisation requirement of €106 billion from Europe's banks (Banks in the UK are exempt), partly designed to help them contain any sovereign bond losses, though it had been widely hoped that such a fund would be double this amount. Additionally, the banks are obliged to raise their Core Tier 1 Capital Ratio to nine per cent. Last but not least, the other main component to emerge from the Euro Summit was that the bailout fund, the EFSF is to be boosted to €1 trillion, though exactly how this is to be achieved is still being worked out.

With Greece dealt with, if only for the moment, attention veered to Italy and its controversial Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi. One has to wonder whether Mr Berlusconi's image problems reflect badly on his country's ratings from the likes of the credit agencies and amongst his fellow European leaders because the liklihood of Italy defaulting on its, admittedly high National Debt, are exaggerated. This is not to say that there is no chance, but its current Budget Deficit to GDP is much better than many other member states of the EU, including that of Britain.

In the first quarter of 2011, Italy's Budget Deficit to GDP ratio was 5.3 per cent and this dropped to 3.2 per cent in the second quarter according to the Italian National Statistics Office. The major problem, but not just for Italy, is the lack of growth. Mr Berlusconi's own Government admitted to the Italian Parliament in September, that growth for 2011 would likely be 0.7 per cent and that this was forecast to drop to 0.6 per cent for 2012.

This poor growth undoubtedly influenced S&P lowering Italy's credit rating to "A" on 20 September 2011 and predicting that GDP growth would be no better than 0.7 per cent ritht through to 2014. Government officials reacted angrily in Italy and said that they expected to balance the Budget by 2013/14, had passed an austerity budget of €54 billion (also in September) and were planning large asset sales in the relatively near future.

Just goes to show that once the Markets lose confidence it's a devil to get it back and what's true for a country is equally valid for the Eurozone. .

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.