The Evil Within Review: Horror Game Built with True Enthusiasm

The Evil Within

- Developer – Tango Gameworks

- Publisher – Bethesda Softworks

- Platforms – PS4 (tested), PS3, Xbox One, Xbox 360, Windows PC

- Release date – October 14

- Price - £39.99

You can trace not only the history of horror games but the career of Shinji Mikami throughout The Evil Within. With so many mechanics, locations, and pretences borrowed from elsewhere, it often borders on the derivative. But this is clearly the work of someone who understands what is and what isn't worth preserving from the past 20 years of games.

It's a celebration of where the horror game started, how it grew and where it's at now. If I wasn't certain that Mikami was planning a follow-up, I'd say The Evil Within was his swansong.

Basically every major game he's been involved in receives a nod. Enemy behaviours, over-the-shoulder shooting, and some of the late stage set-ups are lifted from Resident Evil 4 – there's even a guy with a chainsaw. Save points meanwhile are tended by an enigmatic, obsequious nurse, redolent of Samantha from Killer7, on which Mikami served as writer.

Even Shadows of the Damned, the flawed Suda51 pet project which Mikami co-produced, gets an acknowledgement, by way of exaggerated blood and gore effects. This is a director reflecting on his career, his collaborations.

Not to lend The Evil Within too much art world credibility, but it's comparable to Inland Empire, by David Lynch, a film that comprises dozens of winks to the auteur's previous work. Onimusha, Vanquish, Devil May Cry: Mikami uses The Evil Within to recount his entire track record.

He also pays homage to other horror staples. The combat in The Evil Within - difficult, sporadic and best avoided - is inspired by The Last of Us. And like that game, The Evil Within relies heavily on the interactive camera for creating tension. It's awkward to control and clings tightly to the player character, making each environment feel claustrophobic and enemies, no matter how close they are, difficult to spot.

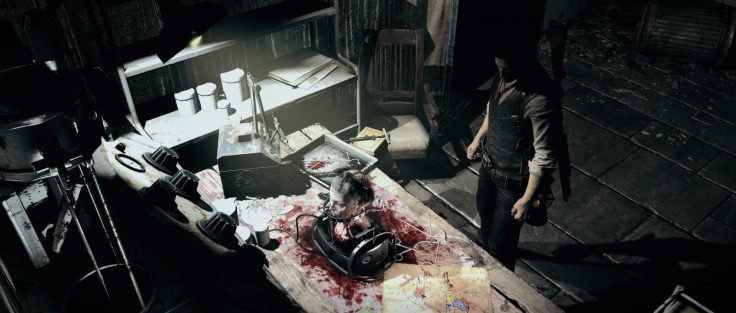

Adding to that sense of enclosure, The Evil Within takes place inside nightmarish, seemingly organic worlds, that repeatedly contort and twist so as to more efficiently beguile the player. A lot of the specific aesthetic touches, the booby-traps, the moving walls, the bloodied floors, remind me of movies, specifically The Cell and Tinto Brass's Caligula.

But the idea of a living, predatory environment, which adapts to torment the main character, has obviously come from the Silent Hill games. Still, Mikami puts his spin on it - The Evil Within is aesthetically more concerned with campish torture devices than phallic or psychological symbols. Arguably, that makes it less sophisticated.

It's certainly less frightening, not just than Silent Hill but the majority of its inspirations. If Mikami created action-horror with Resident Evil 4, on The Evil Within he's pioneered another new genre, something you might coin "entertainment-horror." There are a few ghastly moments, but no real scares. The combat is tense, and you'll suffer a few cheap deaths at the hands of traps and boss enemies, but the sense of oppression and ordeal that lies at the core of good horror isn't present throughout The Evil Within – it vanishes completely in the last few chapters.

What you have instead is an energetic, busy game, with a lot of visual flair. The Evil Within is less concerned with scaring you than with showing you a good time. Section after section, you're introduced to gory spectacle and new enemies. The narrative conceit and art design might suggest horror, but the interface, the platforming sections and the boss battles are all meat and potatoes game design.

Mikami isn't about subversion. Like Rocksteady and the Arkham series, he takes traditional gameplay forms and perfects them, ensuring that opponents are balanced, resources are a luxury and combat areas favour specific tactics which the player must decipher. This kind of expert attention to systems and flow more than makes up for The Evil Within's muted horror. It's only occasionally frightening, but it's always entertaining.

Protagonist Sebastian Castellanos is fantastic. At the best of times, he reminds me of Deadly Premonition's Agent York, since both are completely – refreshingly – unfazed by the insanity around them. The dialogue is at least functional and is used to efficiently relay story beats.

The narrative of The Evil Within only falls down because it tries, in the later chapters, to concretely explain itself. To begin with, the writers are totally unconcerned with what exactly is going on. The Evil Within starts to feel like genuine surrealism. The characters are oddly calm, the sudden changes in environment aren't discussed and no-one has a clue what is happening. It works perfectly. And as Castellanos bounces between horrific, demented scenery, The Evil Within edges on the absurdist. It starts to look like a real art game, unbridled by petty concerns of story or consistence.

But then the antagonist shows up, some phoned-in videogame psychopath, and the cutscenes all turn to exposition. That amusing paradigm, of Castellanos landing inexplicably in a fresh hell, always with an "oh, what now?" look on his face, disappears, to be replaced by some redundant fiction about a failed scientific experiment.

It's such a shame. Clair de Lune is used as a leitmotif and some scenes, like the dream sequence in a field of sunflowers, are truly beautiful. And although classical music and a few picturesque screengrabs aren't shortcuts to class, The Evil Within, with just a little more confidence in its surrealist aspirations, would really stand out among the modern mainstream.

Nevertheless, this is a smart, enjoyable and expertly crafted game, salted with the personality of its director. The artist is present throughout The Evil Within – there isn't a single section that feels half-hearted, or like it's been lifted wholesale from elsewhere. In both the AAA market and the horror genre, which have stagnated for the past five years, a game like The Evil Within – a game built with true enthusiasm – is a rare pleasure.

The Evil Within Review Scores

- Gameplay: 8/10 – Claustrophobic and intense, it's let down only by a few cheap insta-kills which, on a first playthrough, you could never predict.

- Graphics: 9/10 – Not all the monster or level designs stand out, but there's a lot of surreal and nightmarish imagery, all lovingly crafted.

- Sound: 7/10 – Enemies sound appropriately ghastly, particularly one of the early bosses. The music, however, barely registers, except for the expertly placed usages of Clair de Lune.

- Writing: 6/10 – Functional dialogue and some funny moments from Castellanos are let down by the writers' insistence on explaining the minutia of the plot.

- Replay value: 8/10 – Like Resident Evil 4, The Evil Within has dozens of combat sections that you'll want to retry and perfect, until you can complete the entire game in a few hours, taking almost no damage.

- Overall: 9/10 – An intelligent, authored, and consistently entertaining game which combines loving references to the horror genre with the distinctive personality of its director.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.