ExoMars 2016 won't find any aliens – but it's a step in the right direction

Everything you need to know about ExoMars 2016 and the next phase of the mission.

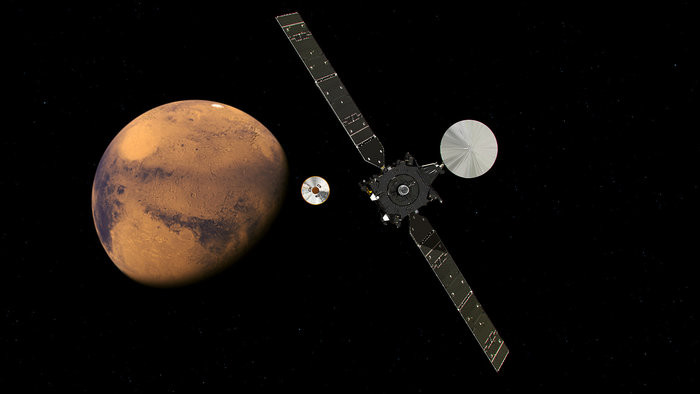

The ExoMars 2016 mission will arrive at its destination on 19 October. The first phase of the European Space Agency's venture to Mars will see an orbiter deployed to better understand the atmosphere of the planet, while the Schiaparelli spacecraft will enter the planet's orbit and deploy a lander to the surface.

Ahead of the arrival, here's everything you need to know about ExoMars 2016

What is the ExoMars mission?

ExoMars is so named as it refers to the "exobiology" (or Exo) of Mars. The mission is to look for the potential existence of life on the red planet. Mars once had vast oceans of liquid water early on in its history – around 3.5 billion years ago. This environment, scientists believe, could have been capable of supporting life. And if life once existed on it, there should be evidence of it still there, in the form of fossil remains for example.

Another intriguing possibility is that life still exists on Mars below its rocky surface. Exploration of some of the harshest environments of Earth has revealed life can thrive in the most inhospitable environments. Known as extremophiles, it is not beyond the realm of possibly that an equivalent life form could exist on Mars.

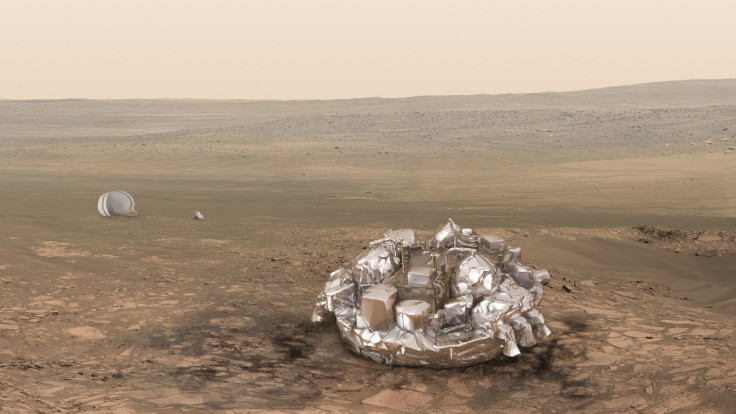

ExoMars 2016 is not looking for aliens

ExoMars 2016 is the first of two missions to Mars. The next, ExoMars 2020, will actively search for signs of past or present alien life, drilling into the surface to analyse materials there. The Schiaparelli spacecraft and lander will be used as a test run, showing the descent, parachute and landing work as they should: "The core purpose of Schiaparelli is as an engineering demonstrator testing key technologies in preparation for ESA's contribution to subsequent missions to Mars, but it also includes a small scientific package for atmospheric studies," the ESA said.

ExoMars 2020 will include a rover that will be deployed to the surface of Mars in order to move around and study the land. This will include drilling down to a depth of 2m to analyse samples with "next generation instruments in an on-board laboratory". Drilling down increases the chance of finding biomarkers – or signs of life – because the Martian atmosphere is thought to be too harsh for any life to survive on the surface.

It is looking for methane though

As well as the Schiaparelli spacecraft, the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) will be deployed as part of the mission. The TGO separated from Schiaparelli on 16 October and performed a correction course so it would not enter Mars' atmosphere.

The main objective for the TGO is to measure trace gasses in the Martian atmosphere, examining their seasonal distributions. Their presence could be the result of life, or it could be from a geological process – the TGO will have to distinguish between the two.

The most important trace gas TGO is looking for is methane. On Earth, methane is created as a by-product of the decomposition of biomass by single-celled organisms called methanogens, such as takes place in the stomachs of cows and sheep.

"Methanogens are believed to have evolved on Earth several billion years ago, before the Earth built up oxygen in its atmosphere," the ESA said. "Since Mars has never had an oxygenated atmosphere, methane in its atmosphere could betray the existence of life similar to Archaea that developed when Mars was warmer and wetter."

There are two potential sources of methane on Mars. "Subsurface microbes could be generating methane directly, pointing to present-day life. But methane could also have been produced millions of years in the past and become trapped in clathrate hydrates (a crystal-like structure of water, similar to ice), only to be released today."

How is ExoMars different from previous missions to Mars?

Previous missions to Mars have not had the sensitivity of ExoMars to detect trace gasses, so this mission will provide better measurements than any other mission before it. Specifically, while we know methane exists on Mars, we do not know where it came from. On Earth, methane has distinctive isotopic signatures allowing scientists to work out if it was the result of biological or geological processes. TGO will be able to do the same for methane on Mars.

Furthermore, ExoMars 2020 will be the first ever mission to combine roving over the surface of Mars with drilling down and taking samples. Compared to Nasa's rovers, which drill down just centimetres, the ExoMars rover will delve up to 2m into the surface of Mars.

"Tests, models and simulations show that to recover well preserved chemical biosignatures from the very early history of Mars (four billion years ago), we need not only to collect samples from a depth of 1.5-2m, but also a site that has been relatively recently uncovered by wind erosion. This site needs to have the right age and deposits where sediments were lain down in a long-lasting water environment," the ESA said.

What happens if we find traces of alien life?

If ExoMars did find traces of alien life, it would still be some time before we could declare its existence. Speaking to IBTimes UK earlier this year, David Parker, director of Human Spaceflight and Robotic Exploration at the ESA, said: "If we found some positive evidence the next thing we'd want to do is send probes to bring rocks or material back from the planet to the Earth and put it in all the laboratories. It's the next big step in robotics exploration and a stepping stone to sending astronauts there and back."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.